Reviewed in 1999 by Roger Ebert

Once upon a time, or maybe twice, there was a land called Pepperland. Eighty thousand leagues beneath the sea it lay, or lie (I'm not too sure).

"Yellow Submarine" was released in 1968, after the Summer of Love but before Woodstock, when the Beatles stood astride the world of pop music, and "psychedelic art" had such an influence that people actually read underground newspapers printed in orange on yellow paper. That was the year "2001: A Space Odyssey" was released in reserved-ticket engagements with an intermission, and hippies would mingle with the ticket holders on the sidewalk outside the theater, and sneak back into the theater for the film's second half, to lay, or lie, flat on their backs on the floor in front of the screen, observing Kubrick's time-space journey from a skewed perspective--while, as the saying went, they were stoned out of their gourds.

"Yellow Submarine" was also embraced as a "head movie," leading to an observation attributed to Ken Kesey: "They say it looks better when you're stoned. But that's true of all movies." All of that was many, many years ago, and now here is a restored version of "Yellow Submarine," arriving like a time capsule from the flower power era, with a graphic look that fuses Peter Max, Rene Magritte and M.C. Escher. To borrow another useful cliche from the 1960s, it blossoms like eye candy on the screen, and with 11 songs by the Beatles it certainly has the best music track of any animated film.

The story begins at a moment of crisis in Pepperland, which is invaded by the music-hating Blue Meanies. They hate the power of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, which has inspired a big YES to sprout near the bandstand, not to mention a towering LOVE and all sorts of bright and cheerful decorations. So the Meanies freeze everything with blue bombs that bleach out the colors and leave Pepperland in a state of blue-gray suspended animation. Old Fred, conductor of the band, escapes the Meanie treatment and flees in the Yellow Submarine to enlist the help of the Beatles.

This is a story that appeals even to young children, but it also has a knowing, funny style that adds an undertow of sophistication. The narration and dialogue are credited to four writers (including "Love Story's" Erich Segal), and yet the overall tone is the one struck by John Lennon in his books In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works. Puns, drolleries, whimsies and asides meander through the sentences:

There's a cyclops! He's got two eyes. Must be a bicyclops. It's a whole bicloplopedia!

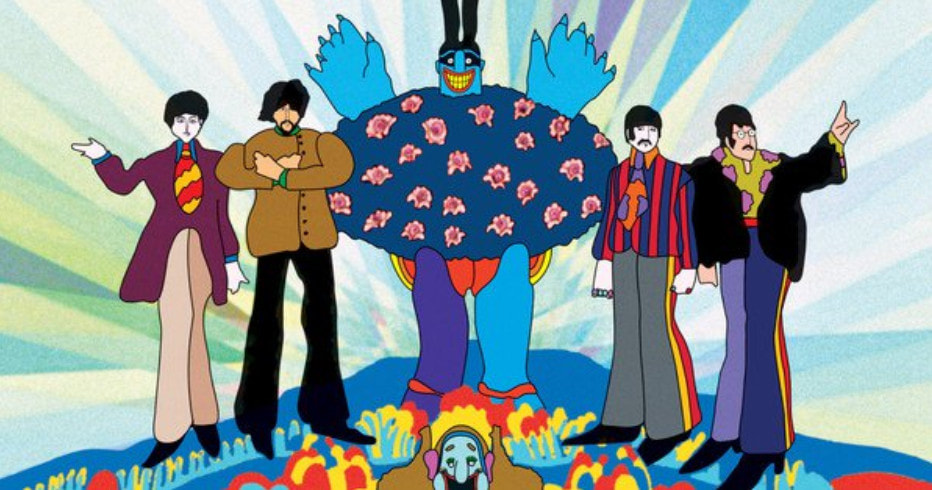

The animation, directed by Tom Halley from Heinz Edelmann's designs, isn't full motion and usually remains within one plane, but there's nothing stiff or limited about it; it has a freedom of color and invention that never tires, and it takes a delight in visual paradoxes. Consider for example the Beatles' visit to the Sea of Holes, a complex Escherian landscape of oval black holes that seem to open up, or down, or sideways, so that the Beatles can enter and emerge in various dimensions.

(Ringo keeps one of the holes, and later gets them out of a tricky situation by remembering, "I've got a hole in my pocket!")

Such dimensional illusions run all through the film. My favorite is a vacuum-nosed creature that snarfs up everything it can find to inhale. Finally it starts on the very frame itself, snuffling it all up into its nose, so that it stands forlorn on a black screen. A pause, and then the creature's attention focuses on its own tail. It attacks that with the vacuum nose and succeeds in inhaling itself, after which nothing at all is left.

The film's visuals borrow from the mind bank of the 20th century. Consider a visit to a sort of image repository where we find Buffalo Bill, Marilyn Monroe, the Phantom, Mandrake the Magician and Frankenstein (who, awakened, turns out to be John Lennon). Dozens of images cascade out of the doors in a long corridor, including Magritte's big green apple and his pipe. And real-life photography is built into other sequences, including the one for "Eleanor Rigby."

Yellow Submarine, like "Fantasia," is a music-based animated film for the ages. The story avoids the usual gee-whiz urgency of so much animation and reflects the same deadpan understatement that the Beatles used in "A Hard Day's Night." Perhaps because the Beatles were considered such a draw, perhaps because the songs were counted on to sell the film, there was no agenda to dumb down the material or hard-sell the story. Instead of contrived urgency, there's unpressured whimsy, and the movie exists as pure charm, expressed in fantastical imagery. And then there are the songs.

This program serves as a fundraiser for the

After Hours Film Society's Anim8 Student Film Festival.

Special Ticket Pricing Applies: $8 Members | $12 Non-Members

Once upon a time, or maybe twice, there was a land called Pepperland. Eighty thousand leagues beneath the sea it lay, or lie (I'm not too sure).

"Yellow Submarine" was released in 1968, after the Summer of Love but before Woodstock, when the Beatles stood astride the world of pop music, and "psychedelic art" had such an influence that people actually read underground newspapers printed in orange on yellow paper. That was the year "2001: A Space Odyssey" was released in reserved-ticket engagements with an intermission, and hippies would mingle with the ticket holders on the sidewalk outside the theater, and sneak back into the theater for the film's second half, to lay, or lie, flat on their backs on the floor in front of the screen, observing Kubrick's time-space journey from a skewed perspective--while, as the saying went, they were stoned out of their gourds.

"Yellow Submarine" was also embraced as a "head movie," leading to an observation attributed to Ken Kesey: "They say it looks better when you're stoned. But that's true of all movies." All of that was many, many years ago, and now here is a restored version of "Yellow Submarine," arriving like a time capsule from the flower power era, with a graphic look that fuses Peter Max, Rene Magritte and M.C. Escher. To borrow another useful cliche from the 1960s, it blossoms like eye candy on the screen, and with 11 songs by the Beatles it certainly has the best music track of any animated film.

The story begins at a moment of crisis in Pepperland, which is invaded by the music-hating Blue Meanies. They hate the power of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, which has inspired a big YES to sprout near the bandstand, not to mention a towering LOVE and all sorts of bright and cheerful decorations. So the Meanies freeze everything with blue bombs that bleach out the colors and leave Pepperland in a state of blue-gray suspended animation. Old Fred, conductor of the band, escapes the Meanie treatment and flees in the Yellow Submarine to enlist the help of the Beatles.

This is a story that appeals even to young children, but it also has a knowing, funny style that adds an undertow of sophistication. The narration and dialogue are credited to four writers (including "Love Story's" Erich Segal), and yet the overall tone is the one struck by John Lennon in his books In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works. Puns, drolleries, whimsies and asides meander through the sentences:

There's a cyclops! He's got two eyes. Must be a bicyclops. It's a whole bicloplopedia!

The animation, directed by Tom Halley from Heinz Edelmann's designs, isn't full motion and usually remains within one plane, but there's nothing stiff or limited about it; it has a freedom of color and invention that never tires, and it takes a delight in visual paradoxes. Consider for example the Beatles' visit to the Sea of Holes, a complex Escherian landscape of oval black holes that seem to open up, or down, or sideways, so that the Beatles can enter and emerge in various dimensions.

(Ringo keeps one of the holes, and later gets them out of a tricky situation by remembering, "I've got a hole in my pocket!")

Such dimensional illusions run all through the film. My favorite is a vacuum-nosed creature that snarfs up everything it can find to inhale. Finally it starts on the very frame itself, snuffling it all up into its nose, so that it stands forlorn on a black screen. A pause, and then the creature's attention focuses on its own tail. It attacks that with the vacuum nose and succeeds in inhaling itself, after which nothing at all is left.

The film's visuals borrow from the mind bank of the 20th century. Consider a visit to a sort of image repository where we find Buffalo Bill, Marilyn Monroe, the Phantom, Mandrake the Magician and Frankenstein (who, awakened, turns out to be John Lennon). Dozens of images cascade out of the doors in a long corridor, including Magritte's big green apple and his pipe. And real-life photography is built into other sequences, including the one for "Eleanor Rigby."

Yellow Submarine, like "Fantasia," is a music-based animated film for the ages. The story avoids the usual gee-whiz urgency of so much animation and reflects the same deadpan understatement that the Beatles used in "A Hard Day's Night." Perhaps because the Beatles were considered such a draw, perhaps because the songs were counted on to sell the film, there was no agenda to dumb down the material or hard-sell the story. Instead of contrived urgency, there's unpressured whimsy, and the movie exists as pure charm, expressed in fantastical imagery. And then there are the songs.

This program serves as a fundraiser for the

After Hours Film Society's Anim8 Student Film Festival.

Special Ticket Pricing Applies: $8 Members | $12 Non-Members

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.