WILD NIGHTS WITH EMILY

Monday, August 19, 7:30 pm

Reviewed by Amy Nicholson / Variety

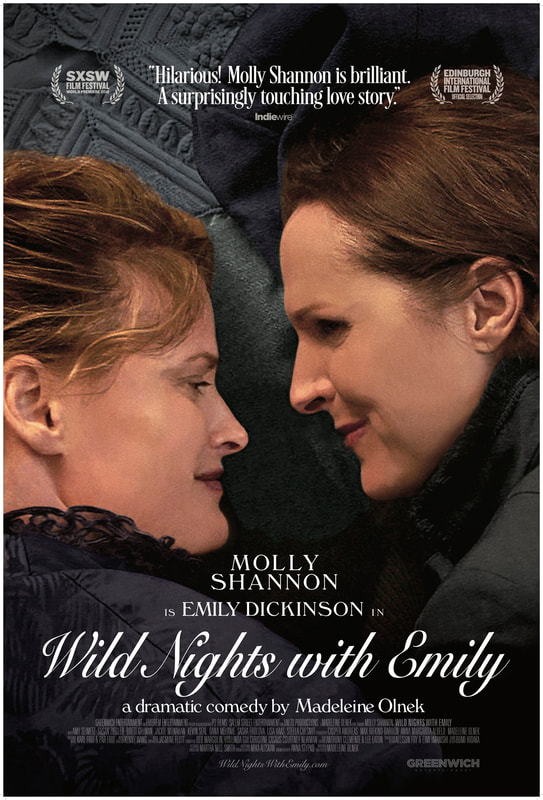

In a plummy warble, a woman named Mabel Todd (Amy Seimetz, hilarious) lectures a rapt audience about her good friend Emily Dickinson (Molly Shannon). No, she never spent any “Wild Nights With Emily,” the tongue-in-cheek title of Madeleine Olnek’s defiant comedy. Honestly, Mabel didn’t know Emily at all. Mabel just disrupted the Dickinson household when she seduced Emily’s brother Austin (Kevin Seal) away from his first wife Susan (Susan Ziegler), the poet’s best friend.

“Wild Nights” is a Victorian vaudeville staged on wobbly facts, but it’s true that Mabel published Emily’s poetry after she died. Thanks to Mabel’s efforts, Emily would posthumously be acknowledged as a brilliant writer and recluse — and thanks to Mabel’s ego, Emily’s refusal to entertain her allowed this home-wrecker to call her a recluse.

Picture Emily today and you’re seeing her through Mabel’s eyes. “A needy spinster,” she sniffs in her ghastly carnation pink satin dress and feathered hat. Emily’s ragged, vivid, rule-breaking stanzas changed history, but it was bitter bystanders like Mabel who wrote it. Olnek’s counterpoint pitches an equally plausible Emily, first seen smooching Susan in the parlor before the secret lovers tumble to the floor. The scene is played for laughs, but Olnek isn’t kidding. Mabel claimed that Emily wrote “Her breast was fit for pearls” for, er, a married male acquaintance named Sam. But analysts later found an erased name on the page: Sue.

Emily scribbled poems on scraps of paper next to recipes for gingerbread. Here, after apologizing to Susan that she’s barely had time to work, she pulls crumpled drafts from her apron, locket, and hair. She wrote over 1,800 poems, but only 11 were published while she was alive — and those were were reworked by male editors who didn’t get this gal’s obsession with dashes and lines that don’t rhyme.

She was ahead of her time and the men who ran the literary world weren’t interested in keeping pace. Instead, in a scathing scene, Emily terrifies “The Atlantic” contributor Thomas Wentworth Higginson (Brett Gelman) when she monologues about her passion for art. The twit flatters himself to be a progressive — “The 19th century is the woman’s century!” he bleats — but not this woman who rattles him with her brain. After fleeing her house, he wrote, “I am glad not to live near her.” Higginson prefers women like Helen Hunt Jackson, who devote themselves to saccharine stanzas about mothers and babies. (As a catty jab, Olnek has actress Cynthia Kaplan recite a verse with the onscreen asterisk: “her actual poetry.”)

Shannon’s Emily doesn’t write for acclaim (although she’s insecure about being ignored). She writes for the only woman who understands her, save for the occasional widow caught sneaking out of her front door, hoop skirts mussed. When Emily coos, “I taste a liquor never brewed,” Susan pauses, puts a hand on her hip, and gasps, “That’s not … oh.” Their relationship jumps to a flashback of young Emily and Susan (Dana Melanie and Sasha Frolova) flirting with each other while reading “Much Ado About Nothing,” and over the next 40 years, blooms into a passionate love story about two women trying to find excuses to be together. (Hence Susan marrying Emily’s brother.) It’s lovely to see Shannon light up with joy. She otherwise spends much of the film looking pursed and dour, suffering through Mabel’s imagination. Mabel would tell fans that Emily wooed an old judge who’d been a friend of her father’s. All Olnek does is put them together — a doddering geezer next to this brilliant rebel — and the institutionalized idea looks absurd.

Of course, Olnek isn’t claiming that “Wild Nights With Emily” should be taken as gospel. She casually reminds the audience that this, too, is fiction. Though the film has the rich look of a period-authentic drama, Olnek shruggingly casts actresses with different colored eyes to play Susan, and when Mabel sits down to play the piano, the soundtrack blasts violins. Later, Emily’s sister Lavinia (Jackie Monahan) pets a clump of fake fur that everyone pretends is a cat. The pre-recorded yowl is a great touch.

Olnek allows a dash of empathy for the vile Mabel. Sexism also stymied her writing ambitions, and when Mabel suggests publishing her letters to Austin, he recoils and tells her to take up pottery. No wonder she needed to smear her fingerprints over her sister-in-law’s art. If the film has a flaw, its that it’s so preoccupied with balancing its furious feminism with gags about Victorian life that there’s little running time to lavish on Dickinson’s actual poetry. We hear snatches of it, and occasionally see her put quill to paper. Only toward the end when Shannon chants “I Died for Beauty” does the film combine all its interests to reach transcendence. “We talked between the rooms,” says Shannon from the eerie darkness of a tomb, “Until the moss had reached our lips, and covered up our names.” Olnek lets stop-motion moss mask Emily’s face. But her movie reclaims Emily’s identity.

In a plummy warble, a woman named Mabel Todd (Amy Seimetz, hilarious) lectures a rapt audience about her good friend Emily Dickinson (Molly Shannon). No, she never spent any “Wild Nights With Emily,” the tongue-in-cheek title of Madeleine Olnek’s defiant comedy. Honestly, Mabel didn’t know Emily at all. Mabel just disrupted the Dickinson household when she seduced Emily’s brother Austin (Kevin Seal) away from his first wife Susan (Susan Ziegler), the poet’s best friend.

“Wild Nights” is a Victorian vaudeville staged on wobbly facts, but it’s true that Mabel published Emily’s poetry after she died. Thanks to Mabel’s efforts, Emily would posthumously be acknowledged as a brilliant writer and recluse — and thanks to Mabel’s ego, Emily’s refusal to entertain her allowed this home-wrecker to call her a recluse.

Picture Emily today and you’re seeing her through Mabel’s eyes. “A needy spinster,” she sniffs in her ghastly carnation pink satin dress and feathered hat. Emily’s ragged, vivid, rule-breaking stanzas changed history, but it was bitter bystanders like Mabel who wrote it. Olnek’s counterpoint pitches an equally plausible Emily, first seen smooching Susan in the parlor before the secret lovers tumble to the floor. The scene is played for laughs, but Olnek isn’t kidding. Mabel claimed that Emily wrote “Her breast was fit for pearls” for, er, a married male acquaintance named Sam. But analysts later found an erased name on the page: Sue.

Emily scribbled poems on scraps of paper next to recipes for gingerbread. Here, after apologizing to Susan that she’s barely had time to work, she pulls crumpled drafts from her apron, locket, and hair. She wrote over 1,800 poems, but only 11 were published while she was alive — and those were were reworked by male editors who didn’t get this gal’s obsession with dashes and lines that don’t rhyme.

She was ahead of her time and the men who ran the literary world weren’t interested in keeping pace. Instead, in a scathing scene, Emily terrifies “The Atlantic” contributor Thomas Wentworth Higginson (Brett Gelman) when she monologues about her passion for art. The twit flatters himself to be a progressive — “The 19th century is the woman’s century!” he bleats — but not this woman who rattles him with her brain. After fleeing her house, he wrote, “I am glad not to live near her.” Higginson prefers women like Helen Hunt Jackson, who devote themselves to saccharine stanzas about mothers and babies. (As a catty jab, Olnek has actress Cynthia Kaplan recite a verse with the onscreen asterisk: “her actual poetry.”)

Shannon’s Emily doesn’t write for acclaim (although she’s insecure about being ignored). She writes for the only woman who understands her, save for the occasional widow caught sneaking out of her front door, hoop skirts mussed. When Emily coos, “I taste a liquor never brewed,” Susan pauses, puts a hand on her hip, and gasps, “That’s not … oh.” Their relationship jumps to a flashback of young Emily and Susan (Dana Melanie and Sasha Frolova) flirting with each other while reading “Much Ado About Nothing,” and over the next 40 years, blooms into a passionate love story about two women trying to find excuses to be together. (Hence Susan marrying Emily’s brother.) It’s lovely to see Shannon light up with joy. She otherwise spends much of the film looking pursed and dour, suffering through Mabel’s imagination. Mabel would tell fans that Emily wooed an old judge who’d been a friend of her father’s. All Olnek does is put them together — a doddering geezer next to this brilliant rebel — and the institutionalized idea looks absurd.

Of course, Olnek isn’t claiming that “Wild Nights With Emily” should be taken as gospel. She casually reminds the audience that this, too, is fiction. Though the film has the rich look of a period-authentic drama, Olnek shruggingly casts actresses with different colored eyes to play Susan, and when Mabel sits down to play the piano, the soundtrack blasts violins. Later, Emily’s sister Lavinia (Jackie Monahan) pets a clump of fake fur that everyone pretends is a cat. The pre-recorded yowl is a great touch.

Olnek allows a dash of empathy for the vile Mabel. Sexism also stymied her writing ambitions, and when Mabel suggests publishing her letters to Austin, he recoils and tells her to take up pottery. No wonder she needed to smear her fingerprints over her sister-in-law’s art. If the film has a flaw, its that it’s so preoccupied with balancing its furious feminism with gags about Victorian life that there’s little running time to lavish on Dickinson’s actual poetry. We hear snatches of it, and occasionally see her put quill to paper. Only toward the end when Shannon chants “I Died for Beauty” does the film combine all its interests to reach transcendence. “We talked between the rooms,” says Shannon from the eerie darkness of a tomb, “Until the moss had reached our lips, and covered up our names.” Olnek lets stop-motion moss mask Emily’s face. But her movie reclaims Emily’s identity.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.