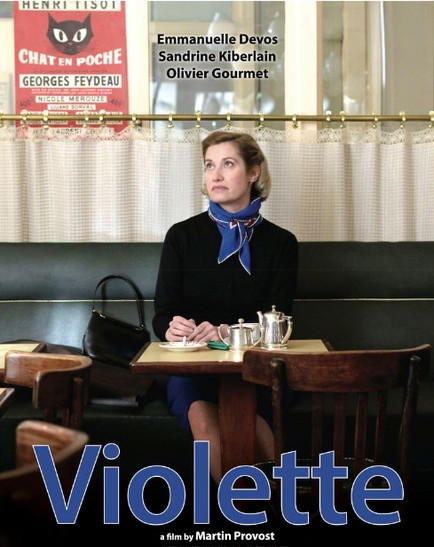

CAST & CREW

Featuring Emmanuelle Devos

Sandrine Kiberlain, & Olivier Gourmet

Directed by Martin Provost

In French with English Subtitles

Not Rated 138 Mins.

Featuring Emmanuelle Devos

Sandrine Kiberlain, & Olivier Gourmet

Directed by Martin Provost

In French with English Subtitles

Not Rated 138 Mins.

Reviewed by Scott Foundas--Variety

The trailblazing feminist writer Violette Leduc gets a biopic fully worthy of her complex life and work with “Violette.” In this thematic bookend to his 2008 “Seraphine,” director Martin Provost once again casts his sharp yet sympathetic gaze on an uncompromising woman artist profoundly at odds with the social and artistic conventions of her day. And once more, he has crafted a plum role that allows a gifted actress (Emmanuelle Devos) to show the full range of her abilities. Commercial prospects look solid for the pic’s Nov. 6 opening in Gaul (where “Seraphine” racked up 846,000 admissions), while the combination of tony literary material and handsome period craftsmanship make it a natural prospect for offshore arthouse distribs.

Provost (who also co-wrote the screenplay with “Seraphine” collaborator Marc Abdelnour and playwright/novelist Rene de Ceccatty) has done an especially fine job here of shaping Leduc’s life into a compelling cinematic narrative, focusing on the roughly 20-year stretch from the end of WWII to her first bestseller (“The Bastard,” published in 1964). He dispenses with the superfluous details that mire most film biographies and instead hones in on the events in Leduc’s life that most affected her writing — and vice-versa — in six elegant chapters. It’s a vivid and varied tale that begins in the waning days of the war, where Leduc makes a living as a black marketer in famine-stricken Paris, while locked in a weirdly codependent relationship with the gay, half-Jewish writer Maurice Sachs (Olivier Py), whose wife she pretends to be. (Leduc herself was bisexual.)

Although Violette has tried her hand at writing (to Sachs’ general lack of encouragement), a chance reading of Simone de Beauvoir’s “She Came to Stay” compels her to embark on her own roman a clef, “L’Asphyxie” (known in English as “In the Prison of Her Skin”), based on her memories of childhood sexual abuse and her relationship with her domineering mother (played brilliantly here by Catherine Hiegel). And this being Paris in the 1940s, where writers and intellectuals were freely accessible to those who wished to engage them, Violette doesn’t think twice about handing off the completed manuscript to Beauvoir (whom she’s never met), fully expecting her to read it — which she does.

It’s the start of a friendship that spans the rest of Leduc’s life, and it becomes the nexus of Provost’s film, with Sandrine Kiberlain making for a wonderfully severe, unflappable Beauvoir in the face of Devos’ undisciplined, emotionally volatile Leduc, a woman who constantly seems to be spilling out of herself. Beauvoir makes everything possible for Leduc: she recognizes in “L’Asphyxie” another bold, original female voice desperate to be heard, gives notes on the text, and recommends it to her friend Albert Camus, who in turn publishes it through his new “Espoir” series (focused on young writers) at Gallimard. Beauvoir also introduces Leduc to a circle of similar envelope-pushing writers and thinkers that includes Jean Genet (Jacques Bonaffe) and the bon vivant collector Jacque Guerin (a delicious Olivier Gourmet). Indeed, the only thing Beauvoir does not give Leduc is her physical love, which the latter openly craves.

Put into the wrong hands, a movie about these characters might have easily descended into kitsch — imagine a gayer, more transgressive “Midnight in Paris” — but as he ably demonstrated in “Seraphine,” Provost is a small master of tact and restraint, and even when Leduc turns her own life into high theater, the movie itself never overplays its hand. Throughout, Provost keeps the focus intently on Leduc’s struggle to find her voice as a writer, to support herself financially, and to overcome her lifelong feelings of illegitimacy (sparked by her having been born out of wedlock). Books come and go, including the heavily censored “Ravages” (in which Leduc wrote openly about her first lesbian relationship, and an abortion), but popular success remains as seemingly unattainable as Beauvoir’s long shadow seems inescapable.

These may be the finest screen hours yet for Devos, who has always excelled at playing private, wounded women (perhaps because she herself refuses to conform to the movies’ one-dimensional ideal of female beauty), and who here gives Leduc a caged-animal intensity. She seems forever on the brink — unrequited in love, unpopular in print — and we see how that sense of rejection feeds back, for better and worse, into her writing. And when Leduc, who has spent her whole life wanting to be desired and accepted, finally feels this way, it’s as if the sun has re-emerged after a prolonged eclipse.

Working with regular Bruno Dumont d.p. Yves Cape, Provost shoots most of the film in a rapturously wintry natural light. And with the aid of production designer Thierry Francois, he gives acute attention to the physical processes of writing — pens scratching across paper, loose pages glued into notebooks — all adding to the film’s hypnotic, sensuous pull.

The trailblazing feminist writer Violette Leduc gets a biopic fully worthy of her complex life and work with “Violette.” In this thematic bookend to his 2008 “Seraphine,” director Martin Provost once again casts his sharp yet sympathetic gaze on an uncompromising woman artist profoundly at odds with the social and artistic conventions of her day. And once more, he has crafted a plum role that allows a gifted actress (Emmanuelle Devos) to show the full range of her abilities. Commercial prospects look solid for the pic’s Nov. 6 opening in Gaul (where “Seraphine” racked up 846,000 admissions), while the combination of tony literary material and handsome period craftsmanship make it a natural prospect for offshore arthouse distribs.

Provost (who also co-wrote the screenplay with “Seraphine” collaborator Marc Abdelnour and playwright/novelist Rene de Ceccatty) has done an especially fine job here of shaping Leduc’s life into a compelling cinematic narrative, focusing on the roughly 20-year stretch from the end of WWII to her first bestseller (“The Bastard,” published in 1964). He dispenses with the superfluous details that mire most film biographies and instead hones in on the events in Leduc’s life that most affected her writing — and vice-versa — in six elegant chapters. It’s a vivid and varied tale that begins in the waning days of the war, where Leduc makes a living as a black marketer in famine-stricken Paris, while locked in a weirdly codependent relationship with the gay, half-Jewish writer Maurice Sachs (Olivier Py), whose wife she pretends to be. (Leduc herself was bisexual.)

Although Violette has tried her hand at writing (to Sachs’ general lack of encouragement), a chance reading of Simone de Beauvoir’s “She Came to Stay” compels her to embark on her own roman a clef, “L’Asphyxie” (known in English as “In the Prison of Her Skin”), based on her memories of childhood sexual abuse and her relationship with her domineering mother (played brilliantly here by Catherine Hiegel). And this being Paris in the 1940s, where writers and intellectuals were freely accessible to those who wished to engage them, Violette doesn’t think twice about handing off the completed manuscript to Beauvoir (whom she’s never met), fully expecting her to read it — which she does.

It’s the start of a friendship that spans the rest of Leduc’s life, and it becomes the nexus of Provost’s film, with Sandrine Kiberlain making for a wonderfully severe, unflappable Beauvoir in the face of Devos’ undisciplined, emotionally volatile Leduc, a woman who constantly seems to be spilling out of herself. Beauvoir makes everything possible for Leduc: she recognizes in “L’Asphyxie” another bold, original female voice desperate to be heard, gives notes on the text, and recommends it to her friend Albert Camus, who in turn publishes it through his new “Espoir” series (focused on young writers) at Gallimard. Beauvoir also introduces Leduc to a circle of similar envelope-pushing writers and thinkers that includes Jean Genet (Jacques Bonaffe) and the bon vivant collector Jacque Guerin (a delicious Olivier Gourmet). Indeed, the only thing Beauvoir does not give Leduc is her physical love, which the latter openly craves.

Put into the wrong hands, a movie about these characters might have easily descended into kitsch — imagine a gayer, more transgressive “Midnight in Paris” — but as he ably demonstrated in “Seraphine,” Provost is a small master of tact and restraint, and even when Leduc turns her own life into high theater, the movie itself never overplays its hand. Throughout, Provost keeps the focus intently on Leduc’s struggle to find her voice as a writer, to support herself financially, and to overcome her lifelong feelings of illegitimacy (sparked by her having been born out of wedlock). Books come and go, including the heavily censored “Ravages” (in which Leduc wrote openly about her first lesbian relationship, and an abortion), but popular success remains as seemingly unattainable as Beauvoir’s long shadow seems inescapable.

These may be the finest screen hours yet for Devos, who has always excelled at playing private, wounded women (perhaps because she herself refuses to conform to the movies’ one-dimensional ideal of female beauty), and who here gives Leduc a caged-animal intensity. She seems forever on the brink — unrequited in love, unpopular in print — and we see how that sense of rejection feeds back, for better and worse, into her writing. And when Leduc, who has spent her whole life wanting to be desired and accepted, finally feels this way, it’s as if the sun has re-emerged after a prolonged eclipse.

Working with regular Bruno Dumont d.p. Yves Cape, Provost shoots most of the film in a rapturously wintry natural light. And with the aid of production designer Thierry Francois, he gives acute attention to the physical processes of writing — pens scratching across paper, loose pages glued into notebooks — all adding to the film’s hypnotic, sensuous pull.