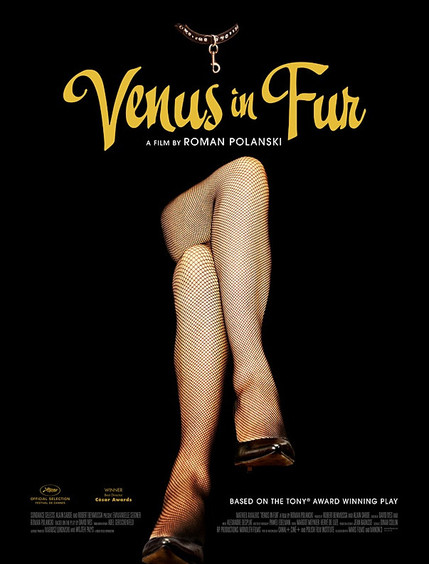

CAST & CREW

With Emmanuelle Seigner and Mathieu Amalric

Directed by Roman Polanski

In French with English Subtitles

Not Rated 96 Mins.

With Emmanuelle Seigner and Mathieu Amalric

Directed by Roman Polanski

In French with English Subtitles

Not Rated 96 Mins.

Reviewed by A.O. Scott--New York Times

Why choose? And why exclude the possibility that the movie is also about Mr. Polanski himself? Working from a French translation of the play (which was widely acclaimed when it ran on and off Broadway a few years ago), Mr. Polanski has marked the text with his own fingerprints. One of the two characters — the splendidly volatile Vanda, an actress — is played by Emmanuelle Seigner, his wife. Her foil — a writer and theater director named Thomas — is played by Mathieu Amalric in a performance that is very close to a Polanski impersonation. Has Mr. Amalric’s stature grown shorter, his nose pointier, or do his haircut and manner simply create the illusion that we are watching a slightly older incarnation of the guy who sliced Jack Nicholson’s nostril in “Chinatown”?

Mr. Polanski, an exile and a fugitive, a Holocaust survivor and a sex offender, has rarely trafficked in explicit autobiography. But in some of his best films, it feels as he is reckoning, at once feverishly and analytically, with his own demons. One of his characteristic preoccupations is claustrophobia. Again and again — in “Repulsion” and “Rosemary’s Baby,” in “The Pianist” and “Carnage” — he zeros in on characters who are trapped in spaces, physical and emotional, that they can neither control nor escape.

Thomas and Vanda are confined, for nearly the entire duration of “Venus in Fur,” in an empty Paris theater. She has arrived late for an audition, stumbling in from the rain-swept street with a burst of excuse-making and oversharing. Thomas, eager to get home to his fiancée and frustrated by the actresses he has seen so far, is unsure whether to indulge Vanda or send her away. He is intrigued that she shares her name with the character in his play, a stage adaptation of Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s 1870 novel, “Venus in Furs,” though he is also dismayed at her vulgar ignorance of its themes. “It’s S-and-M porn, right?” she asks. (Like most things, this sounds much smuttier in French.) He insists that it’s a great love story. But again, why choose?

Polanski at his masterful best. Mathieu Amalric is a dead ringer for the younger Polanski. Powerful and sexy acting deftly rendered.

And in spite of her lack of sophistication, Vanda knows the play by heart, so much that Thomas (and the audience) may begin to suspect that she has walked out of its pages, like Madame Bovary in Woody Allen’s “Kugelmass Episode.” One of the delights of Mr. Ives’s play, and of Mr. Polanski’s nimble rendering of it, is the way it jumps in and out of the play within. As relations between actress and director grow more complicated, the boundary between their various actual and artificial selves twists and blurs. Vanda and Thomas keep turning into Vanda and Kushemski, the dreamy aristocrat at the center of Sacher-Masoch’s fable.

Their relationship is as kinky as a box of paper clips, at once archetypal and timely. Sacher-Masoch, like the Marquis de Sade now better known for his last name than his writing, filtered his tale of erotic humiliation and blissful pain through the mores of his own time and place. “Venus in Fur” does the same, subjecting both Sacher-Masoch’s story and its own characters to the pressures of modern sexual politics. When Vanda calls out the sexism of the original, it is hard to argue with her, though it is certainly possible to quarrel about the feminist and misogynist implications of Mr. Polanski’s film.

What is beyond dispute is the sheer exuberant virtuosity Ms. Seigner and Mr. Amalric bring to the material. He is one of the most reliable — and also one of the least predictable — embodiments of Gallic intellectualism under duress. She is something else entirely: a whirlwind of ferocious intelligence and canny instinct, elusive and magnetic. And she settles the question of what “Venus in Fur” is really about. It’s about acting and the voyeuristic delight, sensual and cerebral in equal measure, that comes from watching it happen.

Why choose? And why exclude the possibility that the movie is also about Mr. Polanski himself? Working from a French translation of the play (which was widely acclaimed when it ran on and off Broadway a few years ago), Mr. Polanski has marked the text with his own fingerprints. One of the two characters — the splendidly volatile Vanda, an actress — is played by Emmanuelle Seigner, his wife. Her foil — a writer and theater director named Thomas — is played by Mathieu Amalric in a performance that is very close to a Polanski impersonation. Has Mr. Amalric’s stature grown shorter, his nose pointier, or do his haircut and manner simply create the illusion that we are watching a slightly older incarnation of the guy who sliced Jack Nicholson’s nostril in “Chinatown”?

Mr. Polanski, an exile and a fugitive, a Holocaust survivor and a sex offender, has rarely trafficked in explicit autobiography. But in some of his best films, it feels as he is reckoning, at once feverishly and analytically, with his own demons. One of his characteristic preoccupations is claustrophobia. Again and again — in “Repulsion” and “Rosemary’s Baby,” in “The Pianist” and “Carnage” — he zeros in on characters who are trapped in spaces, physical and emotional, that they can neither control nor escape.

Thomas and Vanda are confined, for nearly the entire duration of “Venus in Fur,” in an empty Paris theater. She has arrived late for an audition, stumbling in from the rain-swept street with a burst of excuse-making and oversharing. Thomas, eager to get home to his fiancée and frustrated by the actresses he has seen so far, is unsure whether to indulge Vanda or send her away. He is intrigued that she shares her name with the character in his play, a stage adaptation of Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s 1870 novel, “Venus in Furs,” though he is also dismayed at her vulgar ignorance of its themes. “It’s S-and-M porn, right?” she asks. (Like most things, this sounds much smuttier in French.) He insists that it’s a great love story. But again, why choose?

Polanski at his masterful best. Mathieu Amalric is a dead ringer for the younger Polanski. Powerful and sexy acting deftly rendered.

And in spite of her lack of sophistication, Vanda knows the play by heart, so much that Thomas (and the audience) may begin to suspect that she has walked out of its pages, like Madame Bovary in Woody Allen’s “Kugelmass Episode.” One of the delights of Mr. Ives’s play, and of Mr. Polanski’s nimble rendering of it, is the way it jumps in and out of the play within. As relations between actress and director grow more complicated, the boundary between their various actual and artificial selves twists and blurs. Vanda and Thomas keep turning into Vanda and Kushemski, the dreamy aristocrat at the center of Sacher-Masoch’s fable.

Their relationship is as kinky as a box of paper clips, at once archetypal and timely. Sacher-Masoch, like the Marquis de Sade now better known for his last name than his writing, filtered his tale of erotic humiliation and blissful pain through the mores of his own time and place. “Venus in Fur” does the same, subjecting both Sacher-Masoch’s story and its own characters to the pressures of modern sexual politics. When Vanda calls out the sexism of the original, it is hard to argue with her, though it is certainly possible to quarrel about the feminist and misogynist implications of Mr. Polanski’s film.

What is beyond dispute is the sheer exuberant virtuosity Ms. Seigner and Mr. Amalric bring to the material. He is one of the most reliable — and also one of the least predictable — embodiments of Gallic intellectualism under duress. She is something else entirely: a whirlwind of ferocious intelligence and canny instinct, elusive and magnetic. And she settles the question of what “Venus in Fur” is really about. It’s about acting and the voyeuristic delight, sensual and cerebral in equal measure, that comes from watching it happen.