CAST & CREW

Featuring Tim Jenison

Penn Jillette

David Hockney

Director: Teller

Rated PG-13 for some strong language

Running Time: 80 Mins.

Featuring Tim Jenison

Penn Jillette

David Hockney

Director: Teller

Rated PG-13 for some strong language

Running Time: 80 Mins.

Reviewed by Ty Burr - Boston Globe

Some movies are great because of their artistry; “Tim’s Vermeer” achieves greatness — OK, semi-greatness — by placing the act of artistic creation itself under a microscope. On the surface, the documentary is a debunker’s delight: a rigorous, humorous essay on how the great 17th-century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer may have been more ingenious trickster than inspired genius. And it comes to us from a team known for pulling the rug out from under mysteries only to reveal further mysteries and more rugs: the conceptual magic-comedy duo Penn and Teller. And yet the deeper “Tim’s Vermeer” takes you, the peskier and more profound the questions get.

Here’s the gist of it: Tim Jenison, a Texas-based inventor and software developer — he made his fortune with a company called NewTek — got a bee in his bonnet a while back about the methods by which painters re-create reality on canvas. In particular, he started thinking about how artists in 17th-century Netherlands, and Vermeer in particular, may have taken advantage of sophisticated new optics, combined with the centuries-old camera obscura, to pro-ject a scene onto a canvas and trace it from there.

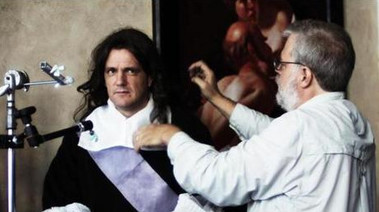

But you can’t trace colors, can you? Widening his inquiry, Jenison started messing about with small mirrors, which is when his old friends, Penn Jillette and Teller, got involved. Teller, who never speaks, decided to direct a movie about this little science project. Penn, who hasn’t stopped speaking in a 30-year career, co-produced the film and is also in front of the camera, goading the pleasantly wonkish Jenison with rude questions.

Teller may be great at catching bullets with his teeth, but he’s not much of a visual stylist: “Tim’s Vermeer” has the bright, bland feel of a well-funded instructional video. In a way, that’s exactly what it is. The aha moment comes when Jenison — who says he has never taken an art course or wielded a palette — uses his mirror-obscura setup to paint a copy of a small photo of his father-in-law. The task is painstaking, tricky, and all at once we’re looking at an eerie replica of the photo. It’s as if the monkeys typed “Hamlet.”

Suddenly the odd photographic “effects” in certain Vermeer paintings (blurrings of focus, gradations of light not noticeable to the human eye) start to make sense. Then Jenison conceives of a truly mad idea: He will re-create the artist’s circa 1662 masterpiece “The Music Lesson.” Actually, that’s not quite correct. He will paint it again. From scratch. The point being that if Vermeer used machines to make his art, anyone can.

The idea is not to replicate what’s on the canvas. The idea is to replicate the same scene Vermeer painted. “Tim’s Vermeer” backs its subject into a lunatic corner when Jenison spends months and a decent chunk of his savings building an exact copy of the painter’s Delft studio in a San Antonio warehouse, down to the floor tiles, wooden rafters, and north-facing windows. Using mannequins in place of humans, he sets up his mirrors and, brush stroke by brush stroke, detail by detail, tries to make “The Music Lesson” a second time.

And here is where all the great conundrums burst through this sharp, funny, tatty documentary. Was Johannes Vermeer a photographer before the invention of photography? After building the room, mixing the paints, and grinding the lenses (by hand!), does Tim Jenison in a sense become Vermeer? If anyone can paint “The Music Lesson” using Tim’s contraption, does that make Vermeer more of a technician and less of an artist? If so, do we value his paintings less? Why? And if you feel betrayed that “Girl With a Pearl Earring” didn’t just stream magically from the artist’s brush, where does that sense of betrayal come from?

The questions keep coming, even as Tim starts to go a little crazy from daubing teensy-weensy beads of painted brocade. Does process make art easier, or just more methodical?

Aren’t brushes and canvas and paint just an earlier form of technology, a process that allows you to get what’s in your head out where others can share it? Is Tim an artist? Is “Tim’s Vermeer” art?

All this in 80 minutes of movie and two years of Jenison’s life. As engaging as it is, though, “Tim’s Vermeer” ends up making a back-door case for Vermeer’s genius, however you want to define the word. The film doesn’t come out and say it (even if it probably should), but the end result of all Jenison’s work is a startlingly faithful copy that holds none of the magic of the original. The sense of looking through a miraculous lens, whether it’s ground glass or a human eye, into a small moment of hushed presence; the mystery of a scene unfolding not for us but for itself, and we’re just privileged to see it; the warmth of a bourgeois Delft interior and all it says about the people and culture who created it — none of this is in Tim’s Vermeer.

Maybe he needs more practice. Or maybe there’s a place where technology, process, and art become inseparable, and a mirror can get you only partway there.

Some movies are great because of their artistry; “Tim’s Vermeer” achieves greatness — OK, semi-greatness — by placing the act of artistic creation itself under a microscope. On the surface, the documentary is a debunker’s delight: a rigorous, humorous essay on how the great 17th-century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer may have been more ingenious trickster than inspired genius. And it comes to us from a team known for pulling the rug out from under mysteries only to reveal further mysteries and more rugs: the conceptual magic-comedy duo Penn and Teller. And yet the deeper “Tim’s Vermeer” takes you, the peskier and more profound the questions get.

Here’s the gist of it: Tim Jenison, a Texas-based inventor and software developer — he made his fortune with a company called NewTek — got a bee in his bonnet a while back about the methods by which painters re-create reality on canvas. In particular, he started thinking about how artists in 17th-century Netherlands, and Vermeer in particular, may have taken advantage of sophisticated new optics, combined with the centuries-old camera obscura, to pro-ject a scene onto a canvas and trace it from there.

But you can’t trace colors, can you? Widening his inquiry, Jenison started messing about with small mirrors, which is when his old friends, Penn Jillette and Teller, got involved. Teller, who never speaks, decided to direct a movie about this little science project. Penn, who hasn’t stopped speaking in a 30-year career, co-produced the film and is also in front of the camera, goading the pleasantly wonkish Jenison with rude questions.

Teller may be great at catching bullets with his teeth, but he’s not much of a visual stylist: “Tim’s Vermeer” has the bright, bland feel of a well-funded instructional video. In a way, that’s exactly what it is. The aha moment comes when Jenison — who says he has never taken an art course or wielded a palette — uses his mirror-obscura setup to paint a copy of a small photo of his father-in-law. The task is painstaking, tricky, and all at once we’re looking at an eerie replica of the photo. It’s as if the monkeys typed “Hamlet.”

Suddenly the odd photographic “effects” in certain Vermeer paintings (blurrings of focus, gradations of light not noticeable to the human eye) start to make sense. Then Jenison conceives of a truly mad idea: He will re-create the artist’s circa 1662 masterpiece “The Music Lesson.” Actually, that’s not quite correct. He will paint it again. From scratch. The point being that if Vermeer used machines to make his art, anyone can.

The idea is not to replicate what’s on the canvas. The idea is to replicate the same scene Vermeer painted. “Tim’s Vermeer” backs its subject into a lunatic corner when Jenison spends months and a decent chunk of his savings building an exact copy of the painter’s Delft studio in a San Antonio warehouse, down to the floor tiles, wooden rafters, and north-facing windows. Using mannequins in place of humans, he sets up his mirrors and, brush stroke by brush stroke, detail by detail, tries to make “The Music Lesson” a second time.

And here is where all the great conundrums burst through this sharp, funny, tatty documentary. Was Johannes Vermeer a photographer before the invention of photography? After building the room, mixing the paints, and grinding the lenses (by hand!), does Tim Jenison in a sense become Vermeer? If anyone can paint “The Music Lesson” using Tim’s contraption, does that make Vermeer more of a technician and less of an artist? If so, do we value his paintings less? Why? And if you feel betrayed that “Girl With a Pearl Earring” didn’t just stream magically from the artist’s brush, where does that sense of betrayal come from?

The questions keep coming, even as Tim starts to go a little crazy from daubing teensy-weensy beads of painted brocade. Does process make art easier, or just more methodical?

Aren’t brushes and canvas and paint just an earlier form of technology, a process that allows you to get what’s in your head out where others can share it? Is Tim an artist? Is “Tim’s Vermeer” art?

All this in 80 minutes of movie and two years of Jenison’s life. As engaging as it is, though, “Tim’s Vermeer” ends up making a back-door case for Vermeer’s genius, however you want to define the word. The film doesn’t come out and say it (even if it probably should), but the end result of all Jenison’s work is a startlingly faithful copy that holds none of the magic of the original. The sense of looking through a miraculous lens, whether it’s ground glass or a human eye, into a small moment of hushed presence; the mystery of a scene unfolding not for us but for itself, and we’re just privileged to see it; the warmth of a bourgeois Delft interior and all it says about the people and culture who created it — none of this is in Tim’s Vermeer.

Maybe he needs more practice. Or maybe there’s a place where technology, process, and art become inseparable, and a mirror can get you only partway there.