CAST & CREW

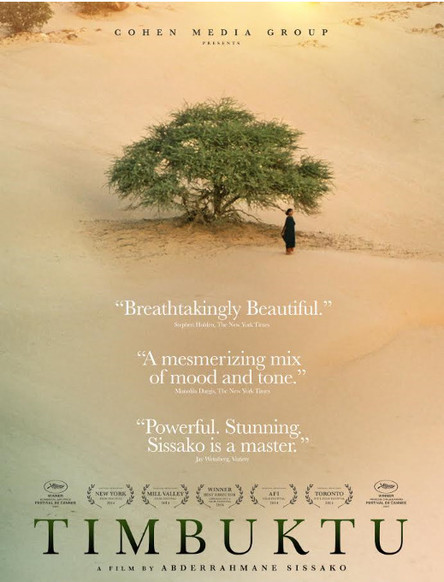

Featuring Ibrahim Ahmed, a.k.a. Pino

Toulou Kiki & Abel Jafri

Directed by Abderrahmane Sissako

In French, Arabic, Bambara, Songhay, Tamasheq

and English with English subtitles

Rated PG-13 97 Mins.

Featuring Ibrahim Ahmed, a.k.a. Pino

Toulou Kiki & Abel Jafri

Directed by Abderrahmane Sissako

In French, Arabic, Bambara, Songhay, Tamasheq

and English with English subtitles

Rated PG-13 97 Mins.

Reviewed by Ann Hornaday - The Washington Post

“Timbuktu” arrives in the nick of time, an alternately unsettling and spellbinding example of humanism and pure visual artistry in the midst of brutality and bloodshed.

At a time when thugs are running rampant under the dubious banner of Islamic pietism and when Westerners nervously wonder where the next threat is coming from, “Timbuktu” returns the focus to those parts of the world where citizens — most of them Muslims — suffer indignity, violence, repression and death not as an abstract worst case but as daily life. Set in the titular city in Mali, this breathtaking, heartbreaking, humbly miraculous movie accomplishes precisely what cinema does at its best: take viewers into a world not their own, invite them to explore it in ways more compassionate than didactic, and leave them feeling perhaps better informed but certainly more connected to people whose aspirations, joys and anxieties aren’t so different from their own.

“Timbuktu’s” chief ambassadors are Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed) and Satima (Toulou Kiki), who live in an open tent in the desert outside Timbuktu with their daughter, Toya (Layla Walet Mohamed), and a young shepherd named Issan (Mehdi A.G. Mohamed). Although jihadists have taken over the city, Kidane and his family are relatively immune to their predations. While bullies patrol the streets with bullhorns banning smoking, soccer and music, and forcing women to wear socks and gloves in the punishing sub- Saharan heat, Satima and Toya can move about freely, their bodies unencumbered. “Our parents raised us in honor without wearing gloves,” Satima says simply.

In time, however, this peaceful countryside existence will collide with the malign forces nearby because of a tragic chain of events involving Kidane’s cows, a grievous error and escalating misunderstandings. Directed with an unerring eye for both intimacy and grandeur by the Mauritanian filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako, “Timbuktu” doesn’t traffic in facile absolutes: As a courageous local imam makes clear when he kicks the interlopers out of his mosque, their behavior has less to do with religion than with the will to power and impunity. Jihad, he reminds them, is about moral improvement, not domination.

Indeed, “Timbuktu” unfolds as something of a grand epic of resistance, whether in the form of that scolding imam, the beautiful songs that can result in torture or Sissako’s own bold choice to make a member of the occupying forces — a covertly smoking Libyan played by Abel Jafri — the butt of a running joke in which his irrational orders have to be translated two or three times to be understood by the local population.

Mehdi A.G. Mohamed, left, plays a young shepherd and Layla Walet Mohamed the daughter of a couple enduring turmoil in Mali in “Timbuktu.” (Cohen Media Group)

Ridiculing moral hypocrisy is always effective, as Sissako knows and keenly demonstrates. But so are wrenching scenes of unspeakable outrage, whether in the brief sight of a man being stoned to death or someone casually decapitating a tuft of hardy desert grass.

With its spectacular sand-swept landscape, lush textures, beguiling music and indomitable, unforgettable protagonists, “Timbuktu” makes an effective case for both a culture and natural world under relentless attack. In providing audiences a chance to bear witness to unspeakable suffering as well as dazzling defiance and human dignity, Sissako has created a film that’s a privilege to watch.

“Timbuktu” arrives in the nick of time, an alternately unsettling and spellbinding example of humanism and pure visual artistry in the midst of brutality and bloodshed.

At a time when thugs are running rampant under the dubious banner of Islamic pietism and when Westerners nervously wonder where the next threat is coming from, “Timbuktu” returns the focus to those parts of the world where citizens — most of them Muslims — suffer indignity, violence, repression and death not as an abstract worst case but as daily life. Set in the titular city in Mali, this breathtaking, heartbreaking, humbly miraculous movie accomplishes precisely what cinema does at its best: take viewers into a world not their own, invite them to explore it in ways more compassionate than didactic, and leave them feeling perhaps better informed but certainly more connected to people whose aspirations, joys and anxieties aren’t so different from their own.

“Timbuktu’s” chief ambassadors are Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed) and Satima (Toulou Kiki), who live in an open tent in the desert outside Timbuktu with their daughter, Toya (Layla Walet Mohamed), and a young shepherd named Issan (Mehdi A.G. Mohamed). Although jihadists have taken over the city, Kidane and his family are relatively immune to their predations. While bullies patrol the streets with bullhorns banning smoking, soccer and music, and forcing women to wear socks and gloves in the punishing sub- Saharan heat, Satima and Toya can move about freely, their bodies unencumbered. “Our parents raised us in honor without wearing gloves,” Satima says simply.

In time, however, this peaceful countryside existence will collide with the malign forces nearby because of a tragic chain of events involving Kidane’s cows, a grievous error and escalating misunderstandings. Directed with an unerring eye for both intimacy and grandeur by the Mauritanian filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako, “Timbuktu” doesn’t traffic in facile absolutes: As a courageous local imam makes clear when he kicks the interlopers out of his mosque, their behavior has less to do with religion than with the will to power and impunity. Jihad, he reminds them, is about moral improvement, not domination.

Indeed, “Timbuktu” unfolds as something of a grand epic of resistance, whether in the form of that scolding imam, the beautiful songs that can result in torture or Sissako’s own bold choice to make a member of the occupying forces — a covertly smoking Libyan played by Abel Jafri — the butt of a running joke in which his irrational orders have to be translated two or three times to be understood by the local population.

Mehdi A.G. Mohamed, left, plays a young shepherd and Layla Walet Mohamed the daughter of a couple enduring turmoil in Mali in “Timbuktu.” (Cohen Media Group)

Ridiculing moral hypocrisy is always effective, as Sissako knows and keenly demonstrates. But so are wrenching scenes of unspeakable outrage, whether in the brief sight of a man being stoned to death or someone casually decapitating a tuft of hardy desert grass.

With its spectacular sand-swept landscape, lush textures, beguiling music and indomitable, unforgettable protagonists, “Timbuktu” makes an effective case for both a culture and natural world under relentless attack. In providing audiences a chance to bear witness to unspeakable suffering as well as dazzling defiance and human dignity, Sissako has created a film that’s a privilege to watch.