“Spellbinding. Elegant and unusual.”

Guy Lodge, Variety

“Both an amazing piece of escapism and incredibly relatable.”

Stephen Saito, The Moveable Fest

“Informed by majesty and wonder, ‘The Velvet Queen’ reveals the humane in nature.”

Robert Abele, Los Angeles Times

Guy Lodge, Variety

“Both an amazing piece of escapism and incredibly relatable.”

Stephen Saito, The Moveable Fest

“Informed by majesty and wonder, ‘The Velvet Queen’ reveals the humane in nature.”

Robert Abele, Los Angeles Times

Reviewed by Guy Lodge | Variety

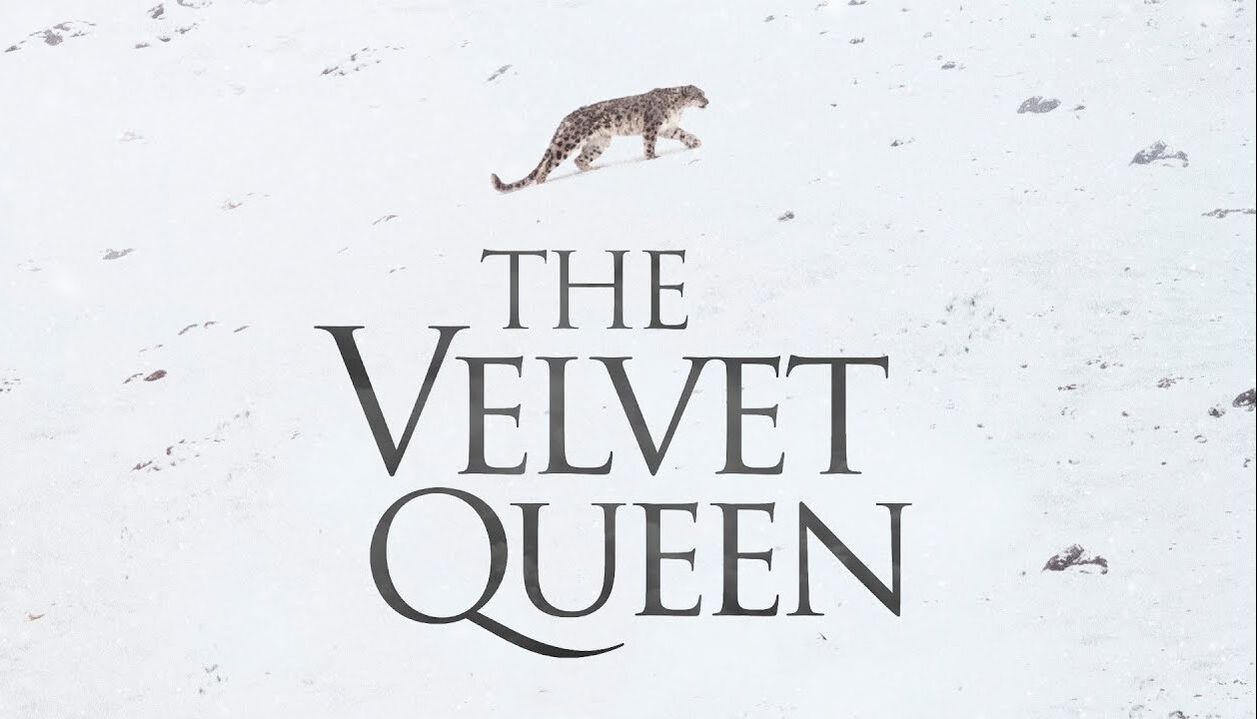

The Velvet Queen

A svelte, slinky figure in spotted silvery blond, the snow leopard is one of the great haughty glamazons of the animal kingdom — a status suitably acknowledged in the English-language title of “The Velvet Queen,” Marie Amiguet and Vincent Munier’s lovely, unexpected screen ode to the little-seen feline. (The original French title is the rather more prosaic “La panthère des neiges.”) Yet if the title implies the naturalist’s equivalent of diva worship, the film’s approach surprises us, fixating less on the furry dazzle of the snow leopard in her natural Tibetan habitat than on the very act of looking at nature in the first place. Following Munier (a leading wildlife photographer) and adventurer Sylvain Tesson on an arduous trek to catch sight of the beast, the doc thoughtfully ponders the conflicted nature of a one-way relationship between watcher and watched.

More art-house than Animal Planet, complete with a sparsely atmospheric score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, the film (which appropriately premiered in Cannes’ new eco-conscious Cinema for the Climate program, and is being released Stateside by Oscilloscope) should find a dedicated audience without becoming a “My Octopus Teacher”-level phenomenon. One suspects its aloof subject won’t mind. Man, after all, is the primary reason the queen in question has become so elusive, with poaching and environmental destruction having slashed Asia’s snow leopard population to grimly endangered levels. And with man, in turn, having subsequently granted her a kind of mythic status for that rarity, “The Velvet Queen” tacitly wonders just what the cat owes her human admirers.

It’s that wry, self-effacing awareness that lends an endearingly quixotic air to the quest, and that separates the film from more plainly spectacle-driven nature documentaries of its ilk. For one thing, Munier and Amiguet — both first-time feature directors, with the latter having previously shot the comparably themed, wolf-oriented 2016 documentary “La vallée des loups” — have little interest in the iridescent, awe-driven aesthetic gloss so popular in its genre. There’s no magic-hour varnish applied to the forbiddingly rugged, taupe-hued vistas of the Tibetan Highlands, the considerable beauty of which nonetheless doesn’t demand to be framed.

Rather, it’s a seemingly barren landscape that requires patience from the onlooker, its manifold forms of life revealing themselves slowly and subtly, often in canny camouflage. Munier and Tesson learn as much, as their repeatedly frustrated journey to find the snow leopard yields other discoveries and points of fascination along the way, just so long as they adapt to the pace of their surroundings. “Waiting was a prayer,” Munier observes, in a sometimes eccentrically abstract voiceover that he and Amiguet also co-scripted. “If nothing came, we just hadn’t looked at it properly.”

And so the audience learns to watch the same way, reveling in other sights, sounds and lifeforms not advertised by the title, as the eponymous monarch keeps us waiting. An extended look at a Tiberan antelope, or a more fleeting one at the lithe, eternally scowling Tibetan fox, is its own reward; even a tiny, orange-breasted lark becomes regal under the filmmakers’ collective gaze, which gradually drinks in an entire ecosystem. Humanity doesn’t get entirely short shrift either, as Munier and Tesson’s dealings with the region’s locals — adults and children alike, who don’t exoticize their native wildlife in the same way — account for some of the film’s wittiest material.

But what of the leopard? After several near-misses and cold trails, our explorers begin to accept that it may have evaded them. “Not everything was created for the human eye,” Munier narrates. That would be a valuable takeaway from the exercise, though “The Velvet Queen” isn’t so austere or perverse as to deny us some closure, and with a first glimpse of a tail coyly curling out from behind a rock formation, the big cat is eventually granted a true screen siren’s entrance. She’s magnificent, of course, but by this time is of a piece with her strange, seductive environment. This elegant, unusual documentary shifts the role of the game-spotter from that of non-violent hunter — in pursuit of one prized target — to passive but duly wide-eyed observer, accepting but also appreciating the limits of our access.

The Velvet Queen

A svelte, slinky figure in spotted silvery blond, the snow leopard is one of the great haughty glamazons of the animal kingdom — a status suitably acknowledged in the English-language title of “The Velvet Queen,” Marie Amiguet and Vincent Munier’s lovely, unexpected screen ode to the little-seen feline. (The original French title is the rather more prosaic “La panthère des neiges.”) Yet if the title implies the naturalist’s equivalent of diva worship, the film’s approach surprises us, fixating less on the furry dazzle of the snow leopard in her natural Tibetan habitat than on the very act of looking at nature in the first place. Following Munier (a leading wildlife photographer) and adventurer Sylvain Tesson on an arduous trek to catch sight of the beast, the doc thoughtfully ponders the conflicted nature of a one-way relationship between watcher and watched.

More art-house than Animal Planet, complete with a sparsely atmospheric score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, the film (which appropriately premiered in Cannes’ new eco-conscious Cinema for the Climate program, and is being released Stateside by Oscilloscope) should find a dedicated audience without becoming a “My Octopus Teacher”-level phenomenon. One suspects its aloof subject won’t mind. Man, after all, is the primary reason the queen in question has become so elusive, with poaching and environmental destruction having slashed Asia’s snow leopard population to grimly endangered levels. And with man, in turn, having subsequently granted her a kind of mythic status for that rarity, “The Velvet Queen” tacitly wonders just what the cat owes her human admirers.

It’s that wry, self-effacing awareness that lends an endearingly quixotic air to the quest, and that separates the film from more plainly spectacle-driven nature documentaries of its ilk. For one thing, Munier and Amiguet — both first-time feature directors, with the latter having previously shot the comparably themed, wolf-oriented 2016 documentary “La vallée des loups” — have little interest in the iridescent, awe-driven aesthetic gloss so popular in its genre. There’s no magic-hour varnish applied to the forbiddingly rugged, taupe-hued vistas of the Tibetan Highlands, the considerable beauty of which nonetheless doesn’t demand to be framed.

Rather, it’s a seemingly barren landscape that requires patience from the onlooker, its manifold forms of life revealing themselves slowly and subtly, often in canny camouflage. Munier and Tesson learn as much, as their repeatedly frustrated journey to find the snow leopard yields other discoveries and points of fascination along the way, just so long as they adapt to the pace of their surroundings. “Waiting was a prayer,” Munier observes, in a sometimes eccentrically abstract voiceover that he and Amiguet also co-scripted. “If nothing came, we just hadn’t looked at it properly.”

And so the audience learns to watch the same way, reveling in other sights, sounds and lifeforms not advertised by the title, as the eponymous monarch keeps us waiting. An extended look at a Tiberan antelope, or a more fleeting one at the lithe, eternally scowling Tibetan fox, is its own reward; even a tiny, orange-breasted lark becomes regal under the filmmakers’ collective gaze, which gradually drinks in an entire ecosystem. Humanity doesn’t get entirely short shrift either, as Munier and Tesson’s dealings with the region’s locals — adults and children alike, who don’t exoticize their native wildlife in the same way — account for some of the film’s wittiest material.

But what of the leopard? After several near-misses and cold trails, our explorers begin to accept that it may have evaded them. “Not everything was created for the human eye,” Munier narrates. That would be a valuable takeaway from the exercise, though “The Velvet Queen” isn’t so austere or perverse as to deny us some closure, and with a first glimpse of a tail coyly curling out from behind a rock formation, the big cat is eventually granted a true screen siren’s entrance. She’s magnificent, of course, but by this time is of a piece with her strange, seductive environment. This elegant, unusual documentary shifts the role of the game-spotter from that of non-violent hunter — in pursuit of one prized target — to passive but duly wide-eyed observer, accepting but also appreciating the limits of our access.