Reviewed by A. O. Scott / New York Times

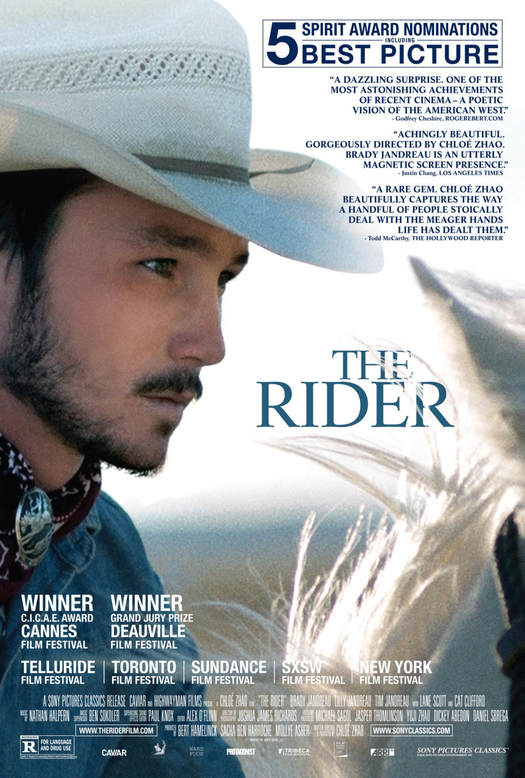

There is a special pleasure in observing a thing done well. In several long, crucial scenes in the middle of “The Rider,” Chloé Zhao’s beautiful second feature, we look on as a young man named Brady Blackburn trains horses, including Apollo, a stubborn and high-spirited colt. A rodeo champion recovering from a serious head injury, Brady understands the animals in a way that suggests both long practice and natural intuition. His total absorption in the task at hand, his graceful combination of discipline and talent, his unshowy confidence in his own skills — all of these are signs that we are watching an artist at work.

Make that two artists. Ms. Zhao’s commitment to her craft — she knows how to take care and when to take risks — matches Brady’s. She has an eye for landscape and an acute sensitivity to the nuances of storytelling, a bold, exacting vision that makes “The Rider” exceptional among recent American regional-realist films. (Ms. Zhao wrote the screenplay; the cinematographer is Joshua James Richards.) Like her debut, “Songs My Brothers Taught Me,” it is alive with empathy and devoid of pity or condescension. There is struggle and disappointment in Brady’s life, but rather than pin him and the other characters down in a tableau of misery, Ms. Zhao honors their essential freedom and understands what is important to them.

The movie takes place on the wide, windy Dakota prairie, where Brady (Brady Jandreau) lives in a trailer with his sister, Lilly (Lilly Jandreau), and their father, Wayne (Tim Jandreau). The actors are nonprofessionals playing versions of themselves — members of a Native American family that has seen its share of hardship. Brady and Lilly, who has an intellectual disability, lost their mother to cancer a few years before. More recently, Brady’s skull was fractured by a bronco in the ring, leaving him with a frightening scar on the side of his head and neurological damage that causes seizures in his right hand. “No more rodeos and no more riding,” a doctor warns, and it’s clear that the injury to Brady’s head has also wounded his morale and his sense of who he is.

And so he grapples with grief, denial and the dreadful feeling that his life is shutting down before it really got started. But he also embraces the pleasures and responsibilities that are part of that new, diminished life: working at the local supermarket, managing the household when Wayne isn’t around, looking out for Lilly, hanging out with his rodeo buddies.

Their evenings around the campfire or at the bar, trading banter and rodeo stories, connect these young men, who proudly see themselves as both Indians and cowboys, with the iconography of the American West. “The Rider” isn’t really a western, but the genre is part of the air it breathes.

Brady is lean and taciturn. His way of talking expresses the stoicism of someone who has been told to “cowboy up” in the face of adversity, but there is also a gentle patience about him. Mr. Jandreau may not have much acting experience, but he has more than a touch of movie-star charisma, that mysterious, unteachable power to hold the screen and galvanize the viewer’s attention.

From time to time, Brady visits his friend Lane (Lane Scott), whose exploits in and out of the rodeo ring have made him a legend among the other riders. Lane is now paralyzed and unable to speak. Brady helps him with physical therapy exercises that mimic sitting up in the saddle and holding onto the reins. They watch old videos of memorable rides, and their refusal to feel sorry for themselves makes their scenes together all the more heartbreaking.

“The Rider,” for the most part, resists both the urge to wallow in sadness and the impulse to deny it. There are a few scenes in which the dialogue does work that would have been better left to the faces of the performers and the details of their environment. We don’t need to hear Brady say to Wayne, “I hope I don’t end up like you.” The fear that he might is present in every glance that passes between father and son. But so is the understanding that Wayne is not only a cautionary figure, battered by loss and disappointment, prone to drinking and gambling and squandering money. He is also a role model, who understands the value of love, loyalty and letting things slide from time to time.

What Brady will become is an open question, a source of considerable suspense and emotion. Wayne falls back on the gambler’s truism about playing the hand you’ve been dealt, but that advice is more complicated than it sounds, and in any case rodeo isn’t like poker. You can’t really bluff or fold. You just hold on for as long as you can, trusting your nerve, your skill and your horse sense.

There is a special pleasure in observing a thing done well. In several long, crucial scenes in the middle of “The Rider,” Chloé Zhao’s beautiful second feature, we look on as a young man named Brady Blackburn trains horses, including Apollo, a stubborn and high-spirited colt. A rodeo champion recovering from a serious head injury, Brady understands the animals in a way that suggests both long practice and natural intuition. His total absorption in the task at hand, his graceful combination of discipline and talent, his unshowy confidence in his own skills — all of these are signs that we are watching an artist at work.

Make that two artists. Ms. Zhao’s commitment to her craft — she knows how to take care and when to take risks — matches Brady’s. She has an eye for landscape and an acute sensitivity to the nuances of storytelling, a bold, exacting vision that makes “The Rider” exceptional among recent American regional-realist films. (Ms. Zhao wrote the screenplay; the cinematographer is Joshua James Richards.) Like her debut, “Songs My Brothers Taught Me,” it is alive with empathy and devoid of pity or condescension. There is struggle and disappointment in Brady’s life, but rather than pin him and the other characters down in a tableau of misery, Ms. Zhao honors their essential freedom and understands what is important to them.

The movie takes place on the wide, windy Dakota prairie, where Brady (Brady Jandreau) lives in a trailer with his sister, Lilly (Lilly Jandreau), and their father, Wayne (Tim Jandreau). The actors are nonprofessionals playing versions of themselves — members of a Native American family that has seen its share of hardship. Brady and Lilly, who has an intellectual disability, lost their mother to cancer a few years before. More recently, Brady’s skull was fractured by a bronco in the ring, leaving him with a frightening scar on the side of his head and neurological damage that causes seizures in his right hand. “No more rodeos and no more riding,” a doctor warns, and it’s clear that the injury to Brady’s head has also wounded his morale and his sense of who he is.

And so he grapples with grief, denial and the dreadful feeling that his life is shutting down before it really got started. But he also embraces the pleasures and responsibilities that are part of that new, diminished life: working at the local supermarket, managing the household when Wayne isn’t around, looking out for Lilly, hanging out with his rodeo buddies.

Their evenings around the campfire or at the bar, trading banter and rodeo stories, connect these young men, who proudly see themselves as both Indians and cowboys, with the iconography of the American West. “The Rider” isn’t really a western, but the genre is part of the air it breathes.

Brady is lean and taciturn. His way of talking expresses the stoicism of someone who has been told to “cowboy up” in the face of adversity, but there is also a gentle patience about him. Mr. Jandreau may not have much acting experience, but he has more than a touch of movie-star charisma, that mysterious, unteachable power to hold the screen and galvanize the viewer’s attention.

From time to time, Brady visits his friend Lane (Lane Scott), whose exploits in and out of the rodeo ring have made him a legend among the other riders. Lane is now paralyzed and unable to speak. Brady helps him with physical therapy exercises that mimic sitting up in the saddle and holding onto the reins. They watch old videos of memorable rides, and their refusal to feel sorry for themselves makes their scenes together all the more heartbreaking.

“The Rider,” for the most part, resists both the urge to wallow in sadness and the impulse to deny it. There are a few scenes in which the dialogue does work that would have been better left to the faces of the performers and the details of their environment. We don’t need to hear Brady say to Wayne, “I hope I don’t end up like you.” The fear that he might is present in every glance that passes between father and son. But so is the understanding that Wayne is not only a cautionary figure, battered by loss and disappointment, prone to drinking and gambling and squandering money. He is also a role model, who understands the value of love, loyalty and letting things slide from time to time.

What Brady will become is an open question, a source of considerable suspense and emotion. Wayne falls back on the gambler’s truism about playing the hand you’ve been dealt, but that advice is more complicated than it sounds, and in any case rodeo isn’t like poker. You can’t really bluff or fold. You just hold on for as long as you can, trusting your nerve, your skill and your horse sense.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.