For among Mongolia's Kazakh people the tradition has always been to allow only men to hunt with these raptors, with Aisholpan's father Nurgaiv, for example, being the 12th male generation of his family to do so.

But when Aisholpan, a bold young person with an open, expressive face, told him she wanted to be trained as well in the ancient art of hunting foxes and other small animals with the massive birds, he did not hesitate to agree. "It's not a choice, it's a calling that has to be in your blood," someone says, and that is very true with her.

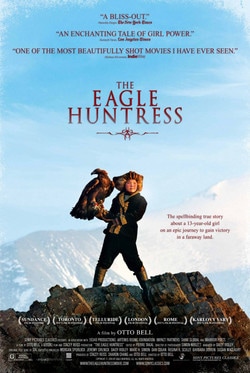

"Eagle Huntress" is set entirely in a starkly beautiful region of Mongolia so remote that director Otto Bell, in an interview at

Sundance, said, "it's not the end of the world, but you can see it from there."

This is Bell's first documentary feature, but he has spent nearly a decade directing shorter, branded content pieces in remote corners of the world, so the film's back-of-the-beyond location did not faze him.

More than that, Bell knew just which colleagues to call on to help, starting with veteran cinematographer Simon Niblett, who brought a self-made drone to capture the film's stunning aerial shots as well as a 30-foot crane that packs away in a case suitable for a snowboard.

Another key collaborator was filmmaker Martina Radwan, who shot some of the more personal moments with Aisholpan, including talking to her friends at school about what this eagle hunting business was all about. Having a more intimate sense of this young woman as someone who both beats the boys at wrestling and paints her younger sister's nails is essential.

Key as well was editor Pierre Takal, who makes it look like Aisholpan's story is telling itself while at the same time blending footage from a whole variety of sources.

This includes, as Bell related at Sundance, scenes that were grabbed with random cameras the first day he met father Nurgaiv, who told the director through a translator, "'Today we're going to steal an eagle chick for Aisholpan to train. Is this the kind of thing you'd be interested in filming?' I said, 'God, yes.'"

No sooner is the chick snared — in a hazardous, heart-in-mouth operation that involves tricky maneuvering down mountain cliffs — than training begins in earnest.

Aisholpan's goal is to be the first woman to take part in the annual Golden Eagle Festival in the Mongolian provincial capital of Olgii, an event that her father has won twice and in which she and her bird, who she names Akkatnat (or White Wings), will compete against some 70 older, more experienced men.

A key segment of "Eagle Huntress" takes place at that contest, which includes the stirring vision of eagles hurtling down from a mountaintop as fast as they can to respond to their master's call.

One of "Eagle Huntress'" more amusing aspects is its use of a kind of Greek chorus of grumpy Kazakh elders who feel that eagle hunting is not something "fragile" women would be advised to take on.

Because these men insist that pursuing foxes in the dead of winter is the ultimate test of who is an eagle hunter and who is not, the film ends by following Aisholpan and her father as they do just that in Mongolia's frigid minus-40-degree weather.

The most impressive thing about "The Eagle Huntress," however, is not Aisholpan's accomplishments, but who she is. Hardworking, intrepid, cheerful, uncomplaining and excited by new challenges, she is not only a role model for young girls, but an exemplar for all of us, whether we plan on hunting with eagles or not.