Reviewed by Leonard Goi / The Film Stage

I wish there was a way I could start this review of Carla Simón’s extraordinary Summer 1993 with its final scene. Not because there are eye-opening or plot-unravelling clues nestled inside it (like many other wonderful recent entries in the coming of age genre – think of Sean Baker’s The Florida Project – Summer 1993 unfolds more like an episodic tale than a plot-thick, action-packed three-act drama), but because it crystallizes what makes Simón’s debut stand out as one of the most memorable in recent years: an effortless ability to capture what it is like to deal with a tragedy of the kind its young heroine undergoes – the way traumas can be compartmentalized, but may always resurface.

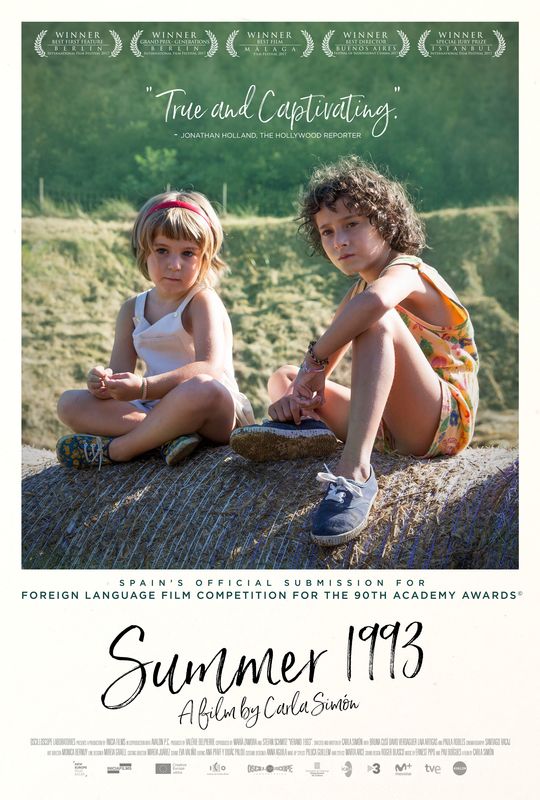

Part of the magic, I suspect, owes to the fact the Catalan 32-year-old writer-director crafted her first feature drawing from her own childhood memories. Summer 1993 chronicles a few hazy weeks in the life of Frida (Laia Artigas), a 6-year-old curly haired girl who, having lost both father and mother, moves away from her grandparents’ Barcelona home to settle with uncle and aunt in the Catalan countryside. We are not told how Frida’s parents died, at least not right away. Simón (aided by collaborating writer Valentina Viso) parsimoniously hints at the tragedy, but does not tell us any more than the adults reveal to its young victim, as both the script and directing follow Frida in the truest sense of the word. The countryside the wide-eyed kid wades through is filmed entirely through her own perspective, as cinematographer Santiago Racaj’s adjusts the camera to Frida’s height – the adults hovering above her often squeezed out of frame – and turns the kid’s new countryside turf into a profoundly tactile and wondrous playground, with scattered p.o.v. shots.

There is a Tati-esque urban-rural dichotomy at play here: shipped away from the buzzing, noisy Barcelona nights, Frida is jettisoned into a completely different universe, a world replete with endless adventures but also governed by rules and rhythms she struggles to adapt to. Out by the garden, hens run around the stone-walled farmhouse; far from the olive trees punctuating the hills, a forest engulfs the farm, tucked deep inside the woods, a river runs through it. It is not all bucolic and idyllic as it seems: sometimes at night thunderstorms knock out power lines, animals are slaughtered by the barn, and Frida’s grandparents – the only remaining link to the old city life, a synecdoche of sorts for her late mother – can only visit every so often, and never as long as she would like them to. As their old white Fiat placidly drives away, Barcelona-bound, Frida resumes her everyday struggle: how to position herself into a family that has unquestioningly decided to adopt her, but is not her own.

Gently paced but not slow, plot-thin yet not uneventful, Summer 1993 feels like a moving letter written by an adult to a much younger self, imbued with the peculiar sadness at the realization the recipient will never be able to read it. Its jaw-dropping and gripping beauty does not stem from a drama-filled storyline, but from the simplicity with which Simón captures the worldview of her alter-ego heroine, and the complex power struggles Frida engages with her new family. There are moments when the child confronts aunt Marga (Bruna Cusí) with the petulance of an underage Monica Vitti (in one remarkable scene, she forces Marga to pull over the car because her hair “doesn’t look right”), others when uncle Esteve (David Verdaguer) acts oblivious to Frida’s desperate attention seeking, and others still when the six-year-old initiates some delightfully creative if heart-wrecking role-playing with her younger cousin, Marga and Esteve’s daughter Anna (Paula Robles). Watching Frida dressed up as an adult, make-up, cowboy boots and big diva-like sunglasses on, a fake cigarette dangling from her lips as she instructs her cousin to call her mum only to push her away (“I’m too tired to play with you, darling”) is a testament to Simón’s outstanding writing talent as much as her skills at directing actors – especially the youngest ones in the cast.

I said I wish I could have started this piece talking about Summer 1993’s poignant ending, but I fear I would do it a disservice, because part of its beauty resides in the way the cathartic moment it ushers in happens, like so many other memorable scenes before it, with so much spontaneity to leave one speechless. I will, however, finish it off by talking about the young actress who embodies that spontaneity with preternatural magnetism: the outstanding Laia Artigas. Casting director Mireia Juárez did not quite simply scout a new enfant prodige, but a force of nature. Whether she is silently observing the adults around her or playing make believe with Anna, the ten-year-old steals every scene she’s in with a swagger, charisma and childlike wonder that echo Mustang’s Lale and Leon The Professional’s Matilda. The soulful expression that congeals in her face as she struggles to find love in a new family shifts between hope and unspeakable sadness, the same way Simón’s debut, susceptible to self-indulgence as any other memoir, dances between the sentimental and the nostalgic to find a miraculous balance between the two.

I wish there was a way I could start this review of Carla Simón’s extraordinary Summer 1993 with its final scene. Not because there are eye-opening or plot-unravelling clues nestled inside it (like many other wonderful recent entries in the coming of age genre – think of Sean Baker’s The Florida Project – Summer 1993 unfolds more like an episodic tale than a plot-thick, action-packed three-act drama), but because it crystallizes what makes Simón’s debut stand out as one of the most memorable in recent years: an effortless ability to capture what it is like to deal with a tragedy of the kind its young heroine undergoes – the way traumas can be compartmentalized, but may always resurface.

Part of the magic, I suspect, owes to the fact the Catalan 32-year-old writer-director crafted her first feature drawing from her own childhood memories. Summer 1993 chronicles a few hazy weeks in the life of Frida (Laia Artigas), a 6-year-old curly haired girl who, having lost both father and mother, moves away from her grandparents’ Barcelona home to settle with uncle and aunt in the Catalan countryside. We are not told how Frida’s parents died, at least not right away. Simón (aided by collaborating writer Valentina Viso) parsimoniously hints at the tragedy, but does not tell us any more than the adults reveal to its young victim, as both the script and directing follow Frida in the truest sense of the word. The countryside the wide-eyed kid wades through is filmed entirely through her own perspective, as cinematographer Santiago Racaj’s adjusts the camera to Frida’s height – the adults hovering above her often squeezed out of frame – and turns the kid’s new countryside turf into a profoundly tactile and wondrous playground, with scattered p.o.v. shots.

There is a Tati-esque urban-rural dichotomy at play here: shipped away from the buzzing, noisy Barcelona nights, Frida is jettisoned into a completely different universe, a world replete with endless adventures but also governed by rules and rhythms she struggles to adapt to. Out by the garden, hens run around the stone-walled farmhouse; far from the olive trees punctuating the hills, a forest engulfs the farm, tucked deep inside the woods, a river runs through it. It is not all bucolic and idyllic as it seems: sometimes at night thunderstorms knock out power lines, animals are slaughtered by the barn, and Frida’s grandparents – the only remaining link to the old city life, a synecdoche of sorts for her late mother – can only visit every so often, and never as long as she would like them to. As their old white Fiat placidly drives away, Barcelona-bound, Frida resumes her everyday struggle: how to position herself into a family that has unquestioningly decided to adopt her, but is not her own.

Gently paced but not slow, plot-thin yet not uneventful, Summer 1993 feels like a moving letter written by an adult to a much younger self, imbued with the peculiar sadness at the realization the recipient will never be able to read it. Its jaw-dropping and gripping beauty does not stem from a drama-filled storyline, but from the simplicity with which Simón captures the worldview of her alter-ego heroine, and the complex power struggles Frida engages with her new family. There are moments when the child confronts aunt Marga (Bruna Cusí) with the petulance of an underage Monica Vitti (in one remarkable scene, she forces Marga to pull over the car because her hair “doesn’t look right”), others when uncle Esteve (David Verdaguer) acts oblivious to Frida’s desperate attention seeking, and others still when the six-year-old initiates some delightfully creative if heart-wrecking role-playing with her younger cousin, Marga and Esteve’s daughter Anna (Paula Robles). Watching Frida dressed up as an adult, make-up, cowboy boots and big diva-like sunglasses on, a fake cigarette dangling from her lips as she instructs her cousin to call her mum only to push her away (“I’m too tired to play with you, darling”) is a testament to Simón’s outstanding writing talent as much as her skills at directing actors – especially the youngest ones in the cast.

I said I wish I could have started this piece talking about Summer 1993’s poignant ending, but I fear I would do it a disservice, because part of its beauty resides in the way the cathartic moment it ushers in happens, like so many other memorable scenes before it, with so much spontaneity to leave one speechless. I will, however, finish it off by talking about the young actress who embodies that spontaneity with preternatural magnetism: the outstanding Laia Artigas. Casting director Mireia Juárez did not quite simply scout a new enfant prodige, but a force of nature. Whether she is silently observing the adults around her or playing make believe with Anna, the ten-year-old steals every scene she’s in with a swagger, charisma and childlike wonder that echo Mustang’s Lale and Leon The Professional’s Matilda. The soulful expression that congeals in her face as she struggles to find love in a new family shifts between hope and unspeakable sadness, the same way Simón’s debut, susceptible to self-indulgence as any other memoir, dances between the sentimental and the nostalgic to find a miraculous balance between the two.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.