Reviewed by A. A. Dowd - A. V. Club

Asked whether they’d rather be a guard or a prisoner, the prospective subjects of what will come to be known as the Stanford Prison Experiment unanimously choose the latter. They’re college kids, after all, and it’s 1971, a good year to be squarely against authority. (As one of them succinctly explains, “Nobody likes guards.”) But the eventual participants—24 male students, all paid $15 a day for their trouble—have no idea what they’re getting into when they sign up for the study, an attempt to observe the psychological effects of working or residing inside a penitentiary. After spending six harrowing days playing jailer or jailed in the bowels of a lecture hall, who among them wouldn’t change his answer? They don’t know it at first, but none of them want to be a prisoner.

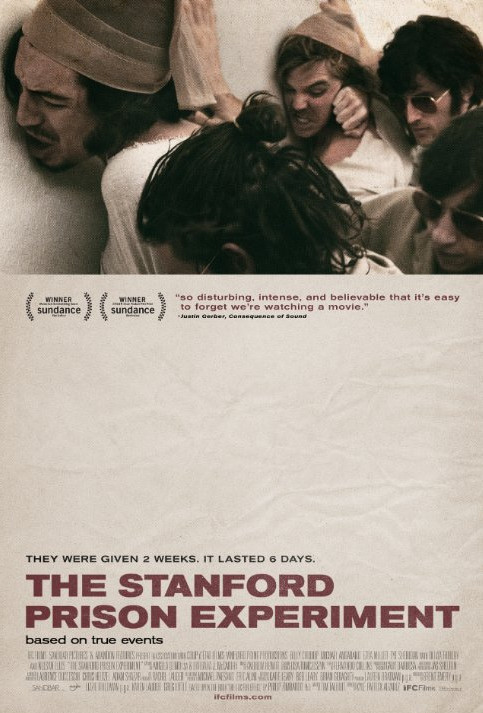

An essential section of any Psych 101 syllabus, the Stanford Prison Experiment has inspired several previous cinematic treatments, including a documentary, a heavily fictionalized German drama, and an American remake of said German drama. Those familiar with how the experiment went down—the internalization of roles, the physical and mental abuse, the refusal of those organizing the study to pull the plug when it quickly got out of hand—won’t be shocked by the details. But there’s still a queasy power to seeing the events restaged with such procedural precision, day by day, blow by (literal) blow. A gripping dramatization, The Stanford Prison Experiment puts its audience in the same position as the head researcher, Dr. Philip Zimbardo: We watch with equal fascination and dread as a group of fresh-faced undergraduates adapt with scary speed to the roles they’re assigned.

Despite having the question posed to them during the interview/audition process, the volunteers have no actual say in what part they’ll be playing: Half are randomly made prisoners, the other half guards. For the first few hours, none of them seem especially fazed by their simulated prison environment, a series of classrooms converted into makeshift cells. Amusement remains high, even as the prisoners are “feminized” through dress-like uniforms and subjected to various minor degradations. Rather quickly, however, everyone gets into character, beginning with the head guard (Michael Angarano) who takes a sadistic shine to authority, modeling his behavior and speech patterns on Strother Martin from Cool Hand Luke. Soon enough, the oppression and captivity begins to feel awfully real to the prisoners, especially when they’re denied personal belongings (a pair of glasses, a bottle of vitamins) or thrown into the hole (a supply closet). Meanwhile, Dr. Lombardo (Billy Crudup) and his fellow researchers watch from surveillance cameras, too seduced by the significance of their findings to realize that, by condoning and even encouraging the cruelty of the guards, they’re becoming part of their own experiment.

Unfolding with both mounting horror and a certain black humor—the belated arrival of a “Day 2” chapter title underlines how fast things got violent—The Stanford Prison Experiment sticks close to the details of its namesake. It’s all so believable, which may seem like a strange thing to say about a true story, but a true story this much stranger than fiction depends on psychologically credible acting. Thankfully, director Kyle Patrick Alvarez, who made the terrific David Sedaris adaptation C.O.G., assembles an impressive ensemble of up-and-coming talent. Tye Sheridan, Thomas Mann, Keir Gilchrist, Lee Ki Hong, Johnny Simmons, and Ezra Miller—the latter typically, especially strong as the first of the prisoners to crack under the pressure—are just a few of the young performers who make strong impressions despite the fact that their characters have no backstories. Whenever it’s behind imaginary bars with lab-rat convicts and their university-empowered oppressors, the film maintains a high level of nauseating intensity. It’s exhausting by design.

Slightly less effective are the scenes of the researchers arguing about the validity of what they’ve sanctioned and whether to intervene. Whereas the prison passages feel ripped from reality—in part because many of them are essentially dramatic reenactments of visual and audio evidence—there’s a certain speculative quality to how Lombardo is depicted, in part because Crudup plays him with a bit too much flared-nostril arrogance. (True to life, it’s the psychologist’s former student/future wife, portrayed by Olivia Thirlby, who helps bring the experiment to a blessedly premature end. This does not, however, make their scenes together seem like less of a distraction.) Then there’s the totally superfluous epilogue, a final attempt to explain the importance of the whole infamous incident. Any textbook chapter on the subject will accomplish the same thing, complete with a deeper discussion of how its horror resonates beyond the boundaries of the experiment to more ugly examples of group think and abuse of power. The Stanford Prison Experiment accomplishes more through the sick charge of its imagery: The disturbing spectacle of college kids stripping other college kids naked, their identities consumed by their “duties,” speaks louder than any academic journal could.

Asked whether they’d rather be a guard or a prisoner, the prospective subjects of what will come to be known as the Stanford Prison Experiment unanimously choose the latter. They’re college kids, after all, and it’s 1971, a good year to be squarely against authority. (As one of them succinctly explains, “Nobody likes guards.”) But the eventual participants—24 male students, all paid $15 a day for their trouble—have no idea what they’re getting into when they sign up for the study, an attempt to observe the psychological effects of working or residing inside a penitentiary. After spending six harrowing days playing jailer or jailed in the bowels of a lecture hall, who among them wouldn’t change his answer? They don’t know it at first, but none of them want to be a prisoner.

An essential section of any Psych 101 syllabus, the Stanford Prison Experiment has inspired several previous cinematic treatments, including a documentary, a heavily fictionalized German drama, and an American remake of said German drama. Those familiar with how the experiment went down—the internalization of roles, the physical and mental abuse, the refusal of those organizing the study to pull the plug when it quickly got out of hand—won’t be shocked by the details. But there’s still a queasy power to seeing the events restaged with such procedural precision, day by day, blow by (literal) blow. A gripping dramatization, The Stanford Prison Experiment puts its audience in the same position as the head researcher, Dr. Philip Zimbardo: We watch with equal fascination and dread as a group of fresh-faced undergraduates adapt with scary speed to the roles they’re assigned.

Despite having the question posed to them during the interview/audition process, the volunteers have no actual say in what part they’ll be playing: Half are randomly made prisoners, the other half guards. For the first few hours, none of them seem especially fazed by their simulated prison environment, a series of classrooms converted into makeshift cells. Amusement remains high, even as the prisoners are “feminized” through dress-like uniforms and subjected to various minor degradations. Rather quickly, however, everyone gets into character, beginning with the head guard (Michael Angarano) who takes a sadistic shine to authority, modeling his behavior and speech patterns on Strother Martin from Cool Hand Luke. Soon enough, the oppression and captivity begins to feel awfully real to the prisoners, especially when they’re denied personal belongings (a pair of glasses, a bottle of vitamins) or thrown into the hole (a supply closet). Meanwhile, Dr. Lombardo (Billy Crudup) and his fellow researchers watch from surveillance cameras, too seduced by the significance of their findings to realize that, by condoning and even encouraging the cruelty of the guards, they’re becoming part of their own experiment.

Unfolding with both mounting horror and a certain black humor—the belated arrival of a “Day 2” chapter title underlines how fast things got violent—The Stanford Prison Experiment sticks close to the details of its namesake. It’s all so believable, which may seem like a strange thing to say about a true story, but a true story this much stranger than fiction depends on psychologically credible acting. Thankfully, director Kyle Patrick Alvarez, who made the terrific David Sedaris adaptation C.O.G., assembles an impressive ensemble of up-and-coming talent. Tye Sheridan, Thomas Mann, Keir Gilchrist, Lee Ki Hong, Johnny Simmons, and Ezra Miller—the latter typically, especially strong as the first of the prisoners to crack under the pressure—are just a few of the young performers who make strong impressions despite the fact that their characters have no backstories. Whenever it’s behind imaginary bars with lab-rat convicts and their university-empowered oppressors, the film maintains a high level of nauseating intensity. It’s exhausting by design.

Slightly less effective are the scenes of the researchers arguing about the validity of what they’ve sanctioned and whether to intervene. Whereas the prison passages feel ripped from reality—in part because many of them are essentially dramatic reenactments of visual and audio evidence—there’s a certain speculative quality to how Lombardo is depicted, in part because Crudup plays him with a bit too much flared-nostril arrogance. (True to life, it’s the psychologist’s former student/future wife, portrayed by Olivia Thirlby, who helps bring the experiment to a blessedly premature end. This does not, however, make their scenes together seem like less of a distraction.) Then there’s the totally superfluous epilogue, a final attempt to explain the importance of the whole infamous incident. Any textbook chapter on the subject will accomplish the same thing, complete with a deeper discussion of how its horror resonates beyond the boundaries of the experiment to more ugly examples of group think and abuse of power. The Stanford Prison Experiment accomplishes more through the sick charge of its imagery: The disturbing spectacle of college kids stripping other college kids naked, their identities consumed by their “duties,” speaks louder than any academic journal could.