PARASITE

Monday, January 20, 7:30 pm

Reviewed by Ty Burr | Boston Globe

Nobody, but nobody, visualizes the war between the haves and the have-nots with more exuberance and ingenuity than the South Korean filmmaking master Bong Joon-ho. In “Snowpiercer” (2013), he put the remnants of humanity on a bullet train endlessly circling the planet, richies in the front and everyone else in steerage. “Okja” (2017) sent a rural farm girl and her genetically modified super-pig to the big city with ferocious comic/karmic results.

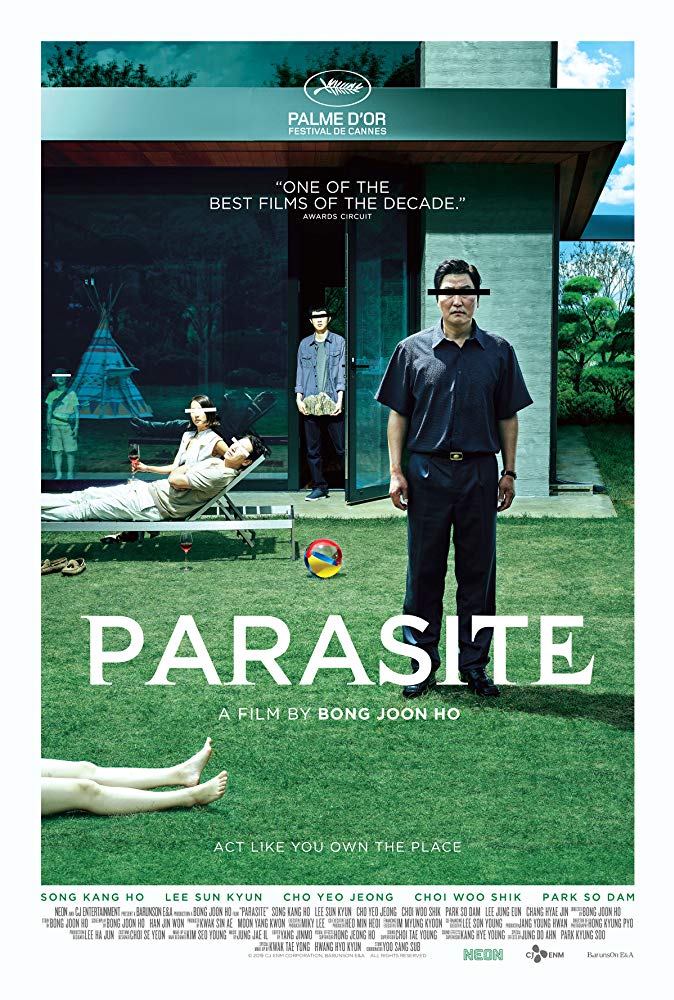

With “Parasite,” Bong forgoes the fantasy elements and delivers his funniest, most biting, and bleakest work to date. The top prizewinner at this year’s Cannes festival, it’s about a family of struggling malcontents — father, mother, sister, brother — who slowly inveigle their way into the home and pampered lives of a wealthy clan, only to find . . . well, far be it from me to spoil any of this sly black comedy’s surprises or to shine a light on the many levels of its daring.

If “Snowpiercer” moved in concentric circles and “Okja” traveled from country to city and back, “Parasite” is visually and thematically a story of social and economic hierarchies and what they do to people. It’s a film about the upper classes, the lower depths, and maybe even the strata below that. Fittingly, we first meet the Kims living in a sub-basement of a Seoul slum near the river, as low as you can get without actually being underwater. Various food-stall businesses run by husband Ki-taek (Bong regular Song Kang-ho) and wife Chung-sook (Jang Hye-jin) have gone belly up, and they’re eking a living folding pizza boxes badly and by the hundreds with their disaffected teenage son, Ki-woo (Choi Woo-sik), and daughter Ki-jung (Park So-dam).

By chance, Ki-woo gets a job tutoring the daughter (Jung Ji-so) of a wealthy tech CEO, Mr. Park (Lee Sun-kyun), and his wife, Yeon-kyo (Jo Yeo-jeong) — a fake college diploma forged by his resourceful and cynical sister getting Ki-woo through the door. The Parks also have a little boy (Jung Hyun-jun) who’s a handful and needs an art therapist (says his mom), so Ki-jung is brought in, pretending to be a friend of a friend of her brother’s.

How to get dad in on the action? A pair of women’s panties placed in the back of Mr. Park’s limo gets the current chauffeur bounced and Ki-taek installed in his place, likewise keeping his identity secret. The Parks’ long-time housekeeper, Moon-gwang (Lee Jong-eun), is a tougher nut to crack, but eventually mom Chung-sook rules the Park roost in her stead. For the time being. The games are really just beginning.

Director Bong combines the cool virtuosity of a Hitchcock with the devilish social satire of Luis Buñuel; at the same time, “Parasite” is exquisitely Korean and very much Bong. Yet the maddening privilege of the Parks — so luxurious and so taken for granted — can be understood by anyone attuned to the absurdities and iniquities of social class. All the performances are sharp as machine-tooled razors, but pride of place might go equally to the great Song as the blowhard patriarch of the poor clan and Jo as the wealthy young mother, who is chic, gullible, and almost touchingly naive. The key word being “almost.”

“Parasite” works as breathless upstairs-downstairs farce at times, as the lowly Kims fantasize about taking the Parks’s elegant architectural playground for themselves. Their employers have all the enraging noblesse oblige of the well-intentioned but clueless rich, and we in the audience register every slight they visit on the family of con artists working for them. We empathize with everyone and no one in “Parasite,” but our sympathies are with the Kims, duplicitous by necessity and clever by nature.

Then, just when we think we know where this movie is going, Bong and his co-writer Han Jin-won reveal entirely unexpected levels of parasitism and survival. With the reappearance of the first housekeeper, accompanied by her husband (Park Myeong-hoon) — I won’t say how or where — “Parasite” becomes a social satire of almost breathless audacity, a three-dimensional chess game of Darwinian one-upmanship that is by turns hilarious, terrifying, and brutal. The viewer understands that blood will out sooner or later; it’s only a matter of whose and how.

“Ooh, how metaphorical,” Ki-woo says early on, as the filmmakers tweak our thirst for allegory. The confidence with which “Parasite” has been put together is almost as bracing as its view of humanity, with Hong Kyung-pyo’s camera steadily prowling the wood-paneled corridors and open-living spaces of the Park home, occasionally glancing at the black rectangle that is the stairway leading . . . below. The smallest details sting: The way the Parks idolize anything American and blithely rename their hirelings “Kevin” and “Jessica.”

The message welling up from the lowest of this movie’s depths is unforgiving and, for all the movie’s wit, quite tragic. The upper classes use who they can and assume it’s their right, while the poor stay poor and feast on each other. Don’t let the title fool you: “Parasite” isn’t really a monster movie. Yet on at least one of its nearly infinite levels it is — and the monsters are us.

Nobody, but nobody, visualizes the war between the haves and the have-nots with more exuberance and ingenuity than the South Korean filmmaking master Bong Joon-ho. In “Snowpiercer” (2013), he put the remnants of humanity on a bullet train endlessly circling the planet, richies in the front and everyone else in steerage. “Okja” (2017) sent a rural farm girl and her genetically modified super-pig to the big city with ferocious comic/karmic results.

With “Parasite,” Bong forgoes the fantasy elements and delivers his funniest, most biting, and bleakest work to date. The top prizewinner at this year’s Cannes festival, it’s about a family of struggling malcontents — father, mother, sister, brother — who slowly inveigle their way into the home and pampered lives of a wealthy clan, only to find . . . well, far be it from me to spoil any of this sly black comedy’s surprises or to shine a light on the many levels of its daring.

If “Snowpiercer” moved in concentric circles and “Okja” traveled from country to city and back, “Parasite” is visually and thematically a story of social and economic hierarchies and what they do to people. It’s a film about the upper classes, the lower depths, and maybe even the strata below that. Fittingly, we first meet the Kims living in a sub-basement of a Seoul slum near the river, as low as you can get without actually being underwater. Various food-stall businesses run by husband Ki-taek (Bong regular Song Kang-ho) and wife Chung-sook (Jang Hye-jin) have gone belly up, and they’re eking a living folding pizza boxes badly and by the hundreds with their disaffected teenage son, Ki-woo (Choi Woo-sik), and daughter Ki-jung (Park So-dam).

By chance, Ki-woo gets a job tutoring the daughter (Jung Ji-so) of a wealthy tech CEO, Mr. Park (Lee Sun-kyun), and his wife, Yeon-kyo (Jo Yeo-jeong) — a fake college diploma forged by his resourceful and cynical sister getting Ki-woo through the door. The Parks also have a little boy (Jung Hyun-jun) who’s a handful and needs an art therapist (says his mom), so Ki-jung is brought in, pretending to be a friend of a friend of her brother’s.

How to get dad in on the action? A pair of women’s panties placed in the back of Mr. Park’s limo gets the current chauffeur bounced and Ki-taek installed in his place, likewise keeping his identity secret. The Parks’ long-time housekeeper, Moon-gwang (Lee Jong-eun), is a tougher nut to crack, but eventually mom Chung-sook rules the Park roost in her stead. For the time being. The games are really just beginning.

Director Bong combines the cool virtuosity of a Hitchcock with the devilish social satire of Luis Buñuel; at the same time, “Parasite” is exquisitely Korean and very much Bong. Yet the maddening privilege of the Parks — so luxurious and so taken for granted — can be understood by anyone attuned to the absurdities and iniquities of social class. All the performances are sharp as machine-tooled razors, but pride of place might go equally to the great Song as the blowhard patriarch of the poor clan and Jo as the wealthy young mother, who is chic, gullible, and almost touchingly naive. The key word being “almost.”

“Parasite” works as breathless upstairs-downstairs farce at times, as the lowly Kims fantasize about taking the Parks’s elegant architectural playground for themselves. Their employers have all the enraging noblesse oblige of the well-intentioned but clueless rich, and we in the audience register every slight they visit on the family of con artists working for them. We empathize with everyone and no one in “Parasite,” but our sympathies are with the Kims, duplicitous by necessity and clever by nature.

Then, just when we think we know where this movie is going, Bong and his co-writer Han Jin-won reveal entirely unexpected levels of parasitism and survival. With the reappearance of the first housekeeper, accompanied by her husband (Park Myeong-hoon) — I won’t say how or where — “Parasite” becomes a social satire of almost breathless audacity, a three-dimensional chess game of Darwinian one-upmanship that is by turns hilarious, terrifying, and brutal. The viewer understands that blood will out sooner or later; it’s only a matter of whose and how.

“Ooh, how metaphorical,” Ki-woo says early on, as the filmmakers tweak our thirst for allegory. The confidence with which “Parasite” has been put together is almost as bracing as its view of humanity, with Hong Kyung-pyo’s camera steadily prowling the wood-paneled corridors and open-living spaces of the Park home, occasionally glancing at the black rectangle that is the stairway leading . . . below. The smallest details sting: The way the Parks idolize anything American and blithely rename their hirelings “Kevin” and “Jessica.”

The message welling up from the lowest of this movie’s depths is unforgiving and, for all the movie’s wit, quite tragic. The upper classes use who they can and assume it’s their right, while the poor stay poor and feast on each other. Don’t let the title fool you: “Parasite” isn’t really a monster movie. Yet on at least one of its nearly infinite levels it is — and the monsters are us.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.