ONE CHILD NATION

Monday, November 11, 7:30 pm

Reviewed by Manohla Dargis / New York Times

Soul-baring and furious, the documentary “One Child Nation” takes a powerful, unflinching look at China’s present through its past. The main subject is the decades-old policy that the country embraced in the late 1970s to limit population growth.

In Dec. 1982, China ratified a constitution that decreed, “Both husband and wife have the duty to practice family planning.” Another blandly worded constitutional article suggested the threat that hung over this duty: “The state promotes family planning so that population growth may fit the plans for economic and social development.”

In 85 minutes, the directors Nanfu Wang and Jialing Zhang unpack that threat — and what it meant existentially for citizens and especially women — with clarity, concision and strategically restrained outrage. It’s a tough movie; at times, it feels almost unbearable. There are images here that you wish you’d never seen. I’ve watched “One Child Nation” twice, at times through tears, but there’s nothing in it that’s gratuitously exploitative. It is instead an essential account of one battle in the continuing war over women’s bodies, one that, Wang forcefully observes, is in no way limited to China. (In 2015, China ended the one-child policy, allowing married couples to have two children.)

Wang serves as both the narrator and an engaging way into the story. (She also edited the movie and shares the cinematography credit with Yuanchen Liu.) After some preliminary text, the filmmakers deftly commence chronicling Wang’s story, which wends through the documentary, wedding the personal to the political. (Both Wang and Zhang were born in China.) Speaking in English and using a combination of archival and originally shot material, Wang introduces her family, including the younger brother who would have been abandoned if he had been born a girl.

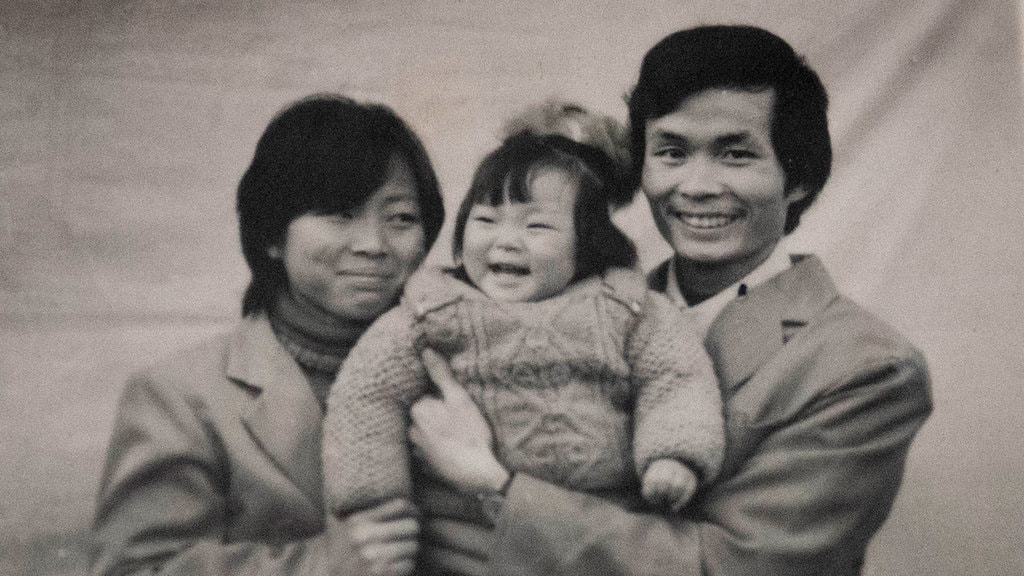

Born in 1985, Wang now is based in New York but the birth of her son brought her emotionally back to China. “Becoming a mother,” she says with unforced feeling, “felt like giving birth to my memories.” As she sifts through her past, Wang speaks about her parents, including the father who died young, and explains the significance of her name. Nan means man, she says, and Fu means pillar. “They hoped for a boy,” she says, reminiscing over a series of childhood photographs. “When I was born a girl they named me Nanfu anyway,” she continues, “hoping that I would grow up strong like a man.” Her voice doesn’t express any obvious editorializing; it doesn’t have to.

This intimate, inviting narration has its tactical uses, and dovetails with the deceptively casual manner in which “One Child Nation” unfolds. After her son is born, Wang returns to her hometown in the Jiangxi province of eastern China. Before long she is chatting with her mother about ordinary life (“Everything is a lot better,” Mom declares); at another point soon after, Wang visits some wary locals, including a former village chief, now in his 70s, who describes how the one-child policy was executed. These conversations, in turn, open into a larger, complex exploration of government policy and politics that grows more unsettling with each revelation.

The history the filmmakers excavate is complex and the personal stories are often brutal. To administer the one-child policy, China instituted a national task force that included family-planning workers and relied on propaganda, surveillance and worse. Enforcement could be draconian. Families that didn’t cooperate had their homes destroyed and their possessions seized. Women endured forced sterilizations and late-term abortions; a midwife says she performed tens of thousands of sterilizations and abortions, adding, “Many I induced alive and killed.” Families found their own ways of dealing with the policy, including abandoning infant girls in hopes that the next child would be a boy. Rural families could have a second child if the first was a girl.

Wang’s mother tells her that “when I was about to give birth to your brother,” her grandmother said: “If it’s another girl, we’ll put her in the basket and leave her in the street.”

It’s ghastly, and while you may want to look away, Wang and Zhang keep you watching. The documentary’s personal quality, it turns out, isn’t simply appealing; it also establishes a tight, empathetic bond between you and the filmmakers — particularly Wang — that grows stronger as the story progresses. As they begin looking into the history of the one-child policy and its ramifications — a horrific chapter involves abandoned newborns, kidnapped children, human trafficking and orphanages — you are not just following Wang down an investigative rabbit hole. You are also worrying about someone poking around in official government business. (Wang’s documentary “Hooligan Sparrow,” about a Chinese activist, provoked similar concerns.)

Wang’s outrage over the one-child policy remains at a steady simmer but is raw and palpable. That’s never truer than when she addresses how everyone, family members and officials alike, insist they had no choice but to comply with the policy. Her anger at this cultivated passivity — “this shared sense of helplessness,” as she puts it — is stark and very moving. Despite this, she and Zhang refuse to demonize those they interview, setting their sights on a larger target. It’s to that end, and perhaps to prevent misunderstandings about their movie, they also remind you of the parallels between China and the United States. Each tries to police a woman’s sovereignty over her body.

Soul-baring and furious, the documentary “One Child Nation” takes a powerful, unflinching look at China’s present through its past. The main subject is the decades-old policy that the country embraced in the late 1970s to limit population growth.

In Dec. 1982, China ratified a constitution that decreed, “Both husband and wife have the duty to practice family planning.” Another blandly worded constitutional article suggested the threat that hung over this duty: “The state promotes family planning so that population growth may fit the plans for economic and social development.”

In 85 minutes, the directors Nanfu Wang and Jialing Zhang unpack that threat — and what it meant existentially for citizens and especially women — with clarity, concision and strategically restrained outrage. It’s a tough movie; at times, it feels almost unbearable. There are images here that you wish you’d never seen. I’ve watched “One Child Nation” twice, at times through tears, but there’s nothing in it that’s gratuitously exploitative. It is instead an essential account of one battle in the continuing war over women’s bodies, one that, Wang forcefully observes, is in no way limited to China. (In 2015, China ended the one-child policy, allowing married couples to have two children.)

Wang serves as both the narrator and an engaging way into the story. (She also edited the movie and shares the cinematography credit with Yuanchen Liu.) After some preliminary text, the filmmakers deftly commence chronicling Wang’s story, which wends through the documentary, wedding the personal to the political. (Both Wang and Zhang were born in China.) Speaking in English and using a combination of archival and originally shot material, Wang introduces her family, including the younger brother who would have been abandoned if he had been born a girl.

Born in 1985, Wang now is based in New York but the birth of her son brought her emotionally back to China. “Becoming a mother,” she says with unforced feeling, “felt like giving birth to my memories.” As she sifts through her past, Wang speaks about her parents, including the father who died young, and explains the significance of her name. Nan means man, she says, and Fu means pillar. “They hoped for a boy,” she says, reminiscing over a series of childhood photographs. “When I was born a girl they named me Nanfu anyway,” she continues, “hoping that I would grow up strong like a man.” Her voice doesn’t express any obvious editorializing; it doesn’t have to.

This intimate, inviting narration has its tactical uses, and dovetails with the deceptively casual manner in which “One Child Nation” unfolds. After her son is born, Wang returns to her hometown in the Jiangxi province of eastern China. Before long she is chatting with her mother about ordinary life (“Everything is a lot better,” Mom declares); at another point soon after, Wang visits some wary locals, including a former village chief, now in his 70s, who describes how the one-child policy was executed. These conversations, in turn, open into a larger, complex exploration of government policy and politics that grows more unsettling with each revelation.

The history the filmmakers excavate is complex and the personal stories are often brutal. To administer the one-child policy, China instituted a national task force that included family-planning workers and relied on propaganda, surveillance and worse. Enforcement could be draconian. Families that didn’t cooperate had their homes destroyed and their possessions seized. Women endured forced sterilizations and late-term abortions; a midwife says she performed tens of thousands of sterilizations and abortions, adding, “Many I induced alive and killed.” Families found their own ways of dealing with the policy, including abandoning infant girls in hopes that the next child would be a boy. Rural families could have a second child if the first was a girl.

Wang’s mother tells her that “when I was about to give birth to your brother,” her grandmother said: “If it’s another girl, we’ll put her in the basket and leave her in the street.”

It’s ghastly, and while you may want to look away, Wang and Zhang keep you watching. The documentary’s personal quality, it turns out, isn’t simply appealing; it also establishes a tight, empathetic bond between you and the filmmakers — particularly Wang — that grows stronger as the story progresses. As they begin looking into the history of the one-child policy and its ramifications — a horrific chapter involves abandoned newborns, kidnapped children, human trafficking and orphanages — you are not just following Wang down an investigative rabbit hole. You are also worrying about someone poking around in official government business. (Wang’s documentary “Hooligan Sparrow,” about a Chinese activist, provoked similar concerns.)

Wang’s outrage over the one-child policy remains at a steady simmer but is raw and palpable. That’s never truer than when she addresses how everyone, family members and officials alike, insist they had no choice but to comply with the policy. Her anger at this cultivated passivity — “this shared sense of helplessness,” as she puts it — is stark and very moving. Despite this, she and Zhang refuse to demonize those they interview, setting their sights on a larger target. It’s to that end, and perhaps to prevent misunderstandings about their movie, they also remind you of the parallels between China and the United States. Each tries to police a woman’s sovereignty over her body.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.