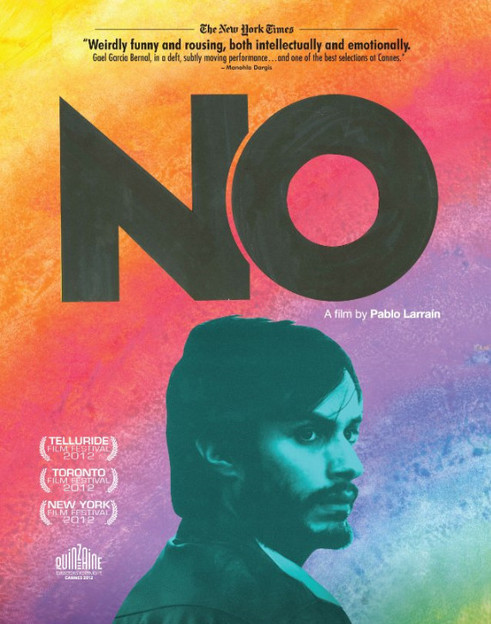

CAST & CREW

Featuring

Alfredo Castro

Antonia Zegers & Gael Garcia Bernal

Directed by Pablo Larrain

In Spanish, with English subtitles

Running time: 118 minutes

Rated R for Language

Featuring

Alfredo Castro

Antonia Zegers & Gael Garcia Bernal

Directed by Pablo Larrain

In Spanish, with English subtitles

Running time: 118 minutes

Rated R for Language

Reviewed by Omer M. Mozaffar

"No" is a terrific film, and word got out very quickly at last year's Cannes Film Festival, where the Chilean docudrama deservedly made a lot of noise even though it played outside the main competition categories. No less than "Argo," "Lincoln" and "Zero Dark Thirty," director Pablo Larrain's achievement feeds the debate regarding truth and fiction and how much of the former a viewer needs when watching a movie that is, by definition, the latter.

Here's why this historical fiction is worth seeing: "No" stands proudly in a select sub-category of historical fiction films that work, completely and satisfyingly, as their own movies. It stars Gael Garcia Bernal as one of Santiago's hotshot "creatives." The character, Rene Saavedra, essentially apolitical at the outset, is the son of a political exile. Rene, who commutes to work on a skateboard, has been separated from his activist wife for some time. He is the primary custodian of their young son; at home, he thinks nothing of kicking his son out of the room so he can commandeer the model train set. It helps him think up ad campaigns selling soda, or soap operas.

Or politics. In 1988, owing to international pressure and to look fair and balanced at home, Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet authorized a plebiscite allowing the citizenry, many of whom had relatives "disappear" or worse under the general's orders, a vote on whether Pinochet deserved eight more years.

Rene, in this version of events, becomes the spearhead of the "no" campaign. Beyond political dissent or one man's dawning realization that he can make a difference, "No" has been described by its director as a study in marketing.

The script makes Rene the object of intense scrutiny from his right-leaning boss. Each new step in the "no" campaign brings upon Rene and his colleagues fresh government surveillance, harassment, serious threats to their livelihoods and their lives. While Pinochet's ad campaign stresses paternalistic authority with a warm glow (at one point Pinochet says, "If I made mistakes ... forgive me"), the "no" campaign focuses on selling happiness and freedom. In real life the monthlong campaign featured endorsements from Jane Fonda, Christopher Reeve and Richard Dreyfuss, seen here in snippets near the end.

It worked, though "No" has taken some heat from various quarters for its focus on one fictional adman, portrayed with enormous skill and charisma by Bernal. Based on a play, the script takes all sorts of legitimate (in my view) liberties with invented characters and situations. (So did "Argo," a film a little less good than this one.)

The real-life director of the "no" ad campaign, Genaro Arriagada, was quoted by The New York Times as calling Larrain's movie "a gross oversimplification that has nothing to do with reality." It's inarguable that "No" leaves out a key component of Pinochet's downfall: the left-wing grass-roots voter registration drive that got enough people to the polls to oust him.

And yet "No" succeeds, wonderfully, because it knows how to sell itself. It is cool, witty, technically dazzling in a low-key and convincing way. The whole film constitutes a rolling bull session, with ideas batted back and forth. Larrain shoots in a low-definition, '88-era approximation of a second-rate video camera of the time, blending archival footage seamlessly. None of the aspects of the story, domestic or political or workplace-focused, feels forced or cheap.

Very much in the "Argo" spirit, we have here, at heart, the tale of a man in marital churn, a devoted father who engineers a bloodless and happy resolution to a geopolitical situation seemingly destined for failure. Simplifications? All over the place. Effective, exciting cinema? Absolutely, and "No" does both sides of the political fence the honor of treating nearly everyone on screen as someone with a brain, if not a fully developed conscience.

"No" is a terrific film, and word got out very quickly at last year's Cannes Film Festival, where the Chilean docudrama deservedly made a lot of noise even though it played outside the main competition categories. No less than "Argo," "Lincoln" and "Zero Dark Thirty," director Pablo Larrain's achievement feeds the debate regarding truth and fiction and how much of the former a viewer needs when watching a movie that is, by definition, the latter.

Here's why this historical fiction is worth seeing: "No" stands proudly in a select sub-category of historical fiction films that work, completely and satisfyingly, as their own movies. It stars Gael Garcia Bernal as one of Santiago's hotshot "creatives." The character, Rene Saavedra, essentially apolitical at the outset, is the son of a political exile. Rene, who commutes to work on a skateboard, has been separated from his activist wife for some time. He is the primary custodian of their young son; at home, he thinks nothing of kicking his son out of the room so he can commandeer the model train set. It helps him think up ad campaigns selling soda, or soap operas.

Or politics. In 1988, owing to international pressure and to look fair and balanced at home, Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet authorized a plebiscite allowing the citizenry, many of whom had relatives "disappear" or worse under the general's orders, a vote on whether Pinochet deserved eight more years.

Rene, in this version of events, becomes the spearhead of the "no" campaign. Beyond political dissent or one man's dawning realization that he can make a difference, "No" has been described by its director as a study in marketing.

The script makes Rene the object of intense scrutiny from his right-leaning boss. Each new step in the "no" campaign brings upon Rene and his colleagues fresh government surveillance, harassment, serious threats to their livelihoods and their lives. While Pinochet's ad campaign stresses paternalistic authority with a warm glow (at one point Pinochet says, "If I made mistakes ... forgive me"), the "no" campaign focuses on selling happiness and freedom. In real life the monthlong campaign featured endorsements from Jane Fonda, Christopher Reeve and Richard Dreyfuss, seen here in snippets near the end.

It worked, though "No" has taken some heat from various quarters for its focus on one fictional adman, portrayed with enormous skill and charisma by Bernal. Based on a play, the script takes all sorts of legitimate (in my view) liberties with invented characters and situations. (So did "Argo," a film a little less good than this one.)

The real-life director of the "no" ad campaign, Genaro Arriagada, was quoted by The New York Times as calling Larrain's movie "a gross oversimplification that has nothing to do with reality." It's inarguable that "No" leaves out a key component of Pinochet's downfall: the left-wing grass-roots voter registration drive that got enough people to the polls to oust him.

And yet "No" succeeds, wonderfully, because it knows how to sell itself. It is cool, witty, technically dazzling in a low-key and convincing way. The whole film constitutes a rolling bull session, with ideas batted back and forth. Larrain shoots in a low-definition, '88-era approximation of a second-rate video camera of the time, blending archival footage seamlessly. None of the aspects of the story, domestic or political or workplace-focused, feels forced or cheap.

Very much in the "Argo" spirit, we have here, at heart, the tale of a man in marital churn, a devoted father who engineers a bloodless and happy resolution to a geopolitical situation seemingly destined for failure. Simplifications? All over the place. Effective, exciting cinema? Absolutely, and "No" does both sides of the political fence the honor of treating nearly everyone on screen as someone with a brain, if not a fully developed conscience.