After Hours Virtual Cinema

New Deal for Artists

By Jennifer Dunning | New York Times | 1981

''I think one of the horrors of our society - American society - is this break with the past, this lack of continuity. Young people know nothing of the past. For that matter, even people who lived through the past have forgotten. And I think the New Deal and its arts projects are a case in point. It's as though they never existed. Not even in the history books. Not even in the memories of people.''

The speaker is Studs Terkel, the writer and oral historian. He speaks from a crowded desk, his head butting exuberantly at the camera. The past to which he refers was a time of paradoxical hope when, out of the country's seemingly irrevocable stumble into economic depression in the mid-1930's grew an innovative and lively public arts program, an unlikely offshoot of a pragmatic plan to provide the millions of jobless Americans across the country with both work and economic relief.

That period in American history has been recalled by a German documentarist in ''The New Deal for Artists,'' a 90-minute film narrated by Orson Welles and written, directed and produced by Wieland Schulz-Keil, a 36-year-old Frankfurt-born filmmaker and publisher who is now living in New York. Made originally for German television, it will be seen in New York on WNET tomorrow evening at 9:30.

In September 1935, $5 billion in Federal funds was allocated to President Roosevelt's New Deal Works Progress Administration, an emergency relief program based on the notion that the unemployed might feel less hopeless if they received relief not as charity but as a salary for work done within their own occupations. With less than one percent of that allocation, the Federal arts projects created programs in theater, art, music and writing, in which some 40,000 professionals in their fields were employed by the end of the year. ''They didn't ask whether you painted this way or that,'' Bernarda Bryson-Shahn, who participated in the Federal Art Project with her husband, the late Ben Shahn, recalls in ''The New Deal for Artists.'' ''They asked whether you needed help.''

''The artists were not paid a lot, but they were not unemployed,'' Mr. Schulz-Keil said. ''That $23.86! The first thing they remember today is that magical figure!'' They earned it in a wide variety of ways, most of them documented in the film's panoramic overview of the creation, administering and dissolution of the programs. Actors took to the fields in truck theater marionette plays or presented ''living newspapers'' in urban theaters for 25 cents a ticket. Artists produced 2,566 murals - many of them still to be seen in post offices across the country, 17,750 municipal sculptures, 110,000 paintings and over a quarter of a million graphic designs including postage stamps. Photographers documented rural poverty for the Farm Security Administration. (''We hoped that time would never be repeated,'' the late Rexford Guy Tugwell, one of the original members of President Roosevelt's Brain Trust, remarks in the film. ''So a record seemed important.'')

Writers compiled highly detailed and still valuable guides to every corner of the United States. ''There were a lot of oral history projects,'' Mr. Schulz-Keil said. ''I came across one by Ralph Ellison, who wrote 'The Invisible Man,' in a library in Boston. It dealt with the image of the sinking of the Titanic and its meaning to blacks. There were black ballads on the subject, some about a black sailor who warned the captain, who wouldn't listen, then swam away when the ship did sink.''

The indigenous and populist arts of the past were rediscovered. Minority artists came to the fore for a time. And new artists developed by working with the more experienced. The arts projects opened up new worlds to both the participating artists and their audiences. ''The American artist finally looked at his own country for his subject matter,'' the painter Aaron Bohrod says in the film. ''New light was thrown on the American character,'' Jerre Mangione, the author and cultural historian and a Federal Writers' Project participant, says in the documentary. ''We found evidence that Americans were not thrifty and hardworking but ingenuous, naive and gambling, tossing coins to establish land boundaries.''

There was a certain amount of naivete among the program's practitioners, too. The Farm Security Administration's photography project, which helped to develop American photo journalism, expressed a typically New Deal reformist attitude as it documented and made public the fact of rural poverty. ''People in Mississippi were thought to be starving because the rich in New York just didn't know about them,'' Mr. Schulz-Keil said.

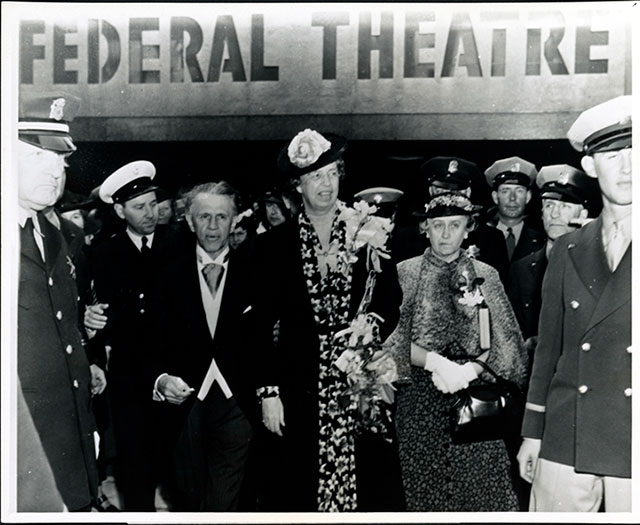

Conceived in suspicion, to murmurs of ''socialism'' and ''communism,'' the arts projects wound down by the end of the decade amid louder cries of dangerous politics and social practices. Though World War II and a growing prosperity played a part in bringing the projects to an end, the greatest blow came with public notice that a guide book to Massachusetts devoted a good deal more space to Sacco and Vanzetti than to the Boston Tea Party, or that a children's theater production ended with the overthrow of ''Ben, the Boss Beaver,'' or that there seemed to be dating among members of the racially integrated cast of ''Haiti,'' a Federal Theater Project in New York City. Martin Dies and his House Un-American Activities Committee had come to power and bore down not only on the programs but on the lives and futures of many of the artists.

Access New Deal for Artists for three days for $10. All sales will help support the After Hours Film Society as we navigate the challenges of COVID-19.

Available Now through July 31

By Jennifer Dunning | New York Times | 1981

''I think one of the horrors of our society - American society - is this break with the past, this lack of continuity. Young people know nothing of the past. For that matter, even people who lived through the past have forgotten. And I think the New Deal and its arts projects are a case in point. It's as though they never existed. Not even in the history books. Not even in the memories of people.''

The speaker is Studs Terkel, the writer and oral historian. He speaks from a crowded desk, his head butting exuberantly at the camera. The past to which he refers was a time of paradoxical hope when, out of the country's seemingly irrevocable stumble into economic depression in the mid-1930's grew an innovative and lively public arts program, an unlikely offshoot of a pragmatic plan to provide the millions of jobless Americans across the country with both work and economic relief.

That period in American history has been recalled by a German documentarist in ''The New Deal for Artists,'' a 90-minute film narrated by Orson Welles and written, directed and produced by Wieland Schulz-Keil, a 36-year-old Frankfurt-born filmmaker and publisher who is now living in New York. Made originally for German television, it will be seen in New York on WNET tomorrow evening at 9:30.

In September 1935, $5 billion in Federal funds was allocated to President Roosevelt's New Deal Works Progress Administration, an emergency relief program based on the notion that the unemployed might feel less hopeless if they received relief not as charity but as a salary for work done within their own occupations. With less than one percent of that allocation, the Federal arts projects created programs in theater, art, music and writing, in which some 40,000 professionals in their fields were employed by the end of the year. ''They didn't ask whether you painted this way or that,'' Bernarda Bryson-Shahn, who participated in the Federal Art Project with her husband, the late Ben Shahn, recalls in ''The New Deal for Artists.'' ''They asked whether you needed help.''

''The artists were not paid a lot, but they were not unemployed,'' Mr. Schulz-Keil said. ''That $23.86! The first thing they remember today is that magical figure!'' They earned it in a wide variety of ways, most of them documented in the film's panoramic overview of the creation, administering and dissolution of the programs. Actors took to the fields in truck theater marionette plays or presented ''living newspapers'' in urban theaters for 25 cents a ticket. Artists produced 2,566 murals - many of them still to be seen in post offices across the country, 17,750 municipal sculptures, 110,000 paintings and over a quarter of a million graphic designs including postage stamps. Photographers documented rural poverty for the Farm Security Administration. (''We hoped that time would never be repeated,'' the late Rexford Guy Tugwell, one of the original members of President Roosevelt's Brain Trust, remarks in the film. ''So a record seemed important.'')

Writers compiled highly detailed and still valuable guides to every corner of the United States. ''There were a lot of oral history projects,'' Mr. Schulz-Keil said. ''I came across one by Ralph Ellison, who wrote 'The Invisible Man,' in a library in Boston. It dealt with the image of the sinking of the Titanic and its meaning to blacks. There were black ballads on the subject, some about a black sailor who warned the captain, who wouldn't listen, then swam away when the ship did sink.''

The indigenous and populist arts of the past were rediscovered. Minority artists came to the fore for a time. And new artists developed by working with the more experienced. The arts projects opened up new worlds to both the participating artists and their audiences. ''The American artist finally looked at his own country for his subject matter,'' the painter Aaron Bohrod says in the film. ''New light was thrown on the American character,'' Jerre Mangione, the author and cultural historian and a Federal Writers' Project participant, says in the documentary. ''We found evidence that Americans were not thrifty and hardworking but ingenuous, naive and gambling, tossing coins to establish land boundaries.''

There was a certain amount of naivete among the program's practitioners, too. The Farm Security Administration's photography project, which helped to develop American photo journalism, expressed a typically New Deal reformist attitude as it documented and made public the fact of rural poverty. ''People in Mississippi were thought to be starving because the rich in New York just didn't know about them,'' Mr. Schulz-Keil said.

Conceived in suspicion, to murmurs of ''socialism'' and ''communism,'' the arts projects wound down by the end of the decade amid louder cries of dangerous politics and social practices. Though World War II and a growing prosperity played a part in bringing the projects to an end, the greatest blow came with public notice that a guide book to Massachusetts devoted a good deal more space to Sacco and Vanzetti than to the Boston Tea Party, or that a children's theater production ended with the overthrow of ''Ben, the Boss Beaver,'' or that there seemed to be dating among members of the racially integrated cast of ''Haiti,'' a Federal Theater Project in New York City. Martin Dies and his House Un-American Activities Committee had come to power and bore down not only on the programs but on the lives and futures of many of the artists.

Access New Deal for Artists for three days for $10. All sales will help support the After Hours Film Society as we navigate the challenges of COVID-19.

Available Now through July 31