have been, and that it scarcely matters if there wasn’t. Drolly and persuasively, the movie demonstrates that when it comes to evoking the artist and the nature of his art, historical fidelity and literal-minded dramatization go only so far. Fiction, lovingly and imaginatively rendered, can bring us much closer to the truth.

“We must dream our way,” Neruda once wrote, and it is nothing short of enchanting to encounter a biographical drama that, rather than merely shoving that quote into its protagonist’s mouth, treats it as a guiding aesthetic and philosophical principle. Like (and yet completely unlike) “I’m Not There,” Todd Haynes’ fragmented 2007 cine-riff on Bob Dylan, “Neruda” is less a straightforward portrait of a great contemporary poet (and eventual Nobel laureate) than a rigorously sustained investigation of his inner world.

Although informed by the busy workings of history, politics and personal affairs, “Neruda” proceeds like a light-footed chase thriller filtered through an episode of “The Twilight Zone,” by the end of which the audience is lost in a crazily spiraling meta-narrative. Who exactly is the star and author of that narrative is one of the film’s more enticing mysteries.

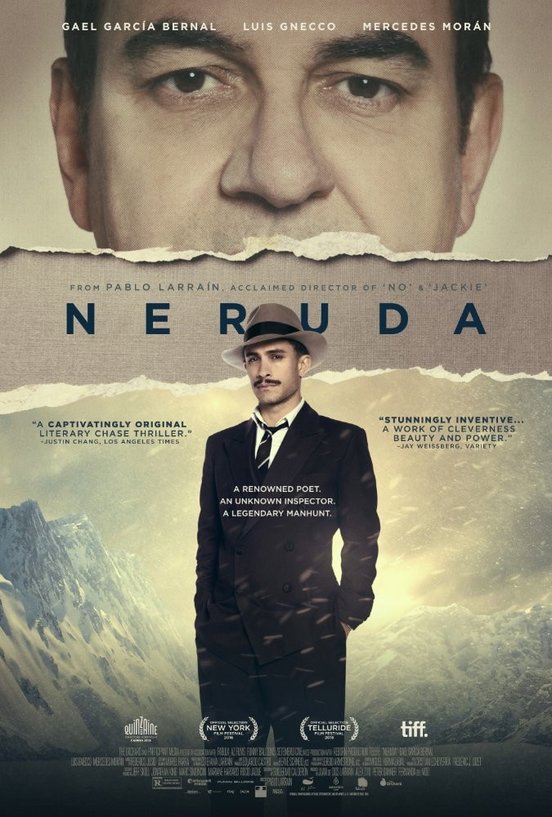

Initially it seems both roles must be filled by Pablo Neruda, played with prickly, preening brilliance by Luis Gnecco (“Narcos”), who donned a wig and gained more than 50 pounds to achieve his remarkable physical resemblance to the real deal. The key to the performance is that, despite the shimmering inspiration of Neruda’s poetry, neither Gnecco nor Larraín seems to feel any obligation to make Neruda himself a particularly inspiring figure.

From the opening scene, a political gathering wittily set in an enormous public lavatory, Neruda, a senator and member of the Chilean Communist Party, is shown to be a proud and vociferous critic of his country’s leadership. But in the very next sequence, a lavish party crammed with half-naked revelers, the film presents the idea of Neruda as a Champagne socialist — a vain, hedonistic hypocrite who, like so many left-wing elites, loves “to soak up other people’s sweat and suffering.”

That damning bit of mockery is delivered by the aforementioned detective, Oscar Peluchonneau (played with mustachioed elan by Gael García Bernal), who slyly complicates the film’s notions of authorship and agency. When Chilean President Gabriel González Videla (Alfredo Castro) outlaws communism in 1948, responding to mounting Cold War anxieties, Peluchonneau eagerly leads the manhunt for Neruda, who has gone into hiding in the port city of Valparaíso with his second wife, the painter Delia del Carril (Mercedes Morán, excellent).

Many of the individual scenes in “Neruda” serve a fairly clear narrative purpose. We see the poet consorting with his allies, arguing with his wife, and disobeying his party-appointed bodyguard (Michael Silva) to slip out for a frolic at a nearby brothel or bohemian enclave. We rarely see him writing, though his poems are shown being secretly distributed and playing a huge role in keeping the communist movement alive underground. But even these relatively simple moments are transformed and complicated by the sheer audacity of Larraín’s stylistic conceits.

In the hands of the editor Hervé Schneid, an extended conversation between two people might span three or four different locations, transporting the viewer without warning from a private room to a perch overlooking the Chilean countryside. Elsewhere, Sergio Armstrong’s sensuous digital photography evokes the mood of the past even as it encourages us to view the film as a formalist construct, from the faded, purplish coloration of the images to the use of phony-looking rear projection in the driving scenes.

In one of Larraín and Calderon’s most telling flourishes, it is Peluchonneau who provides the film’s running voice-over commentary, often in contrapuntal harmony with Neruda’s journey. The two men are almost never seen in the same frame, and yet the ever-mobile camera seems to ping-pong restlessly between them, as though blurring them into one shared, active consciousness.

Peluchonneau’s words may be sardonic and self-flattering, but as the film advances and his own footing in the narrative begins to shift, they also take on their own mysterious, downright Nerudian poetry. (A few verses from his posthumously published “For All to Know” might seem appropriate here: “I am everybody and every time/I always call myself by your name.”)

“Neruda’s” formal spryness and nontraditional appreciation of history will come as little surprise to admirers of “Jackie,” Larraín’s other great bio-experiment of the moment, or his 2012 drama, “No,” a compelling snapshot of the end of the Augusto Pinochet regime that also starred Bernal (with Gnecco and Castro in prominent supporting roles). His filmography, which includes such festival-acclaimed favorites as “Tony Manero,” “Post Mortem” and “The Club,” has sealed his reputation as one of the most distinctive and continually surprising talents in world cinema, though nothing he’s done to date has forced him to take such intuitive leaps, to abandon realism so completely, as “Neruda.”

Unspooling the picture earlier this year at the Cannes Film Festival, Larraín confessed that, even after making the movie, he wasn’t at all sure he knew who Neruda was. And in a typically counter-intuitive gesture, “Neruda” doesn’t pretend to know, either. It keeps the man at a playful distance, firm in its belief that the art will sustain our interest, long after the passing of the artist and his historical moment. It’s possible that Pablo Neruda himself would have concurred with this sentiment, though Oscar Peluchonneau might have begged to differ. In Spanish with English Subtitles.

Please join us for our thought provoking post screening discussion!