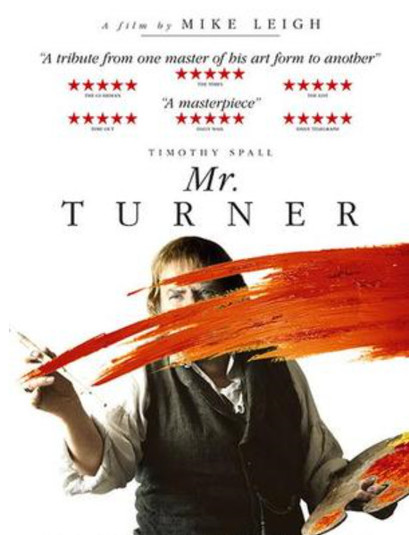

CAST & CREW

Featuring Timothy Spall

Dorothy Atkinson & Marion Bailey

Written & Directed by Mike Leigh

Rated R 149 Mins.

Featuring Timothy Spall

Dorothy Atkinson & Marion Bailey

Written & Directed by Mike Leigh

Rated R 149 Mins.

Reviewed by A. O. Scott - NY Times

“Cynicism has no place in the reviewing of art.” Words to live by, for sure, and all the more so for being uttered by John Ruskin, one of the giants of 19th-century British art criticism. But nothing is quite so simple. In “Mr. Turner,” Mike Leigh’s revelatory new film, Ruskin (Joshua McGuire) appears as a pretentious carrot-topped nitwit with a voice like a posh Elmer Fudd. In one scene, he offers up “controversial” theories about landscapes and seascapes to a roomful of harrumphing artists. It’s all very well, one says, to opine and interpret, but unless you have braved the elements with brush in hand, you don’t really know what you’re talking about.

Fair enough. Though he and his parents are admirers and collectors of good paintings — and steadfast champions of the film’s hero, J. M. W. Turner — the Ruskin of Mr. Leigh’s film is a cruelly etched, cautionary figure, a warning that even those people most passionately devoted to the cause of art are likely to get it wrong. A bit of well-placed cynicism might even be in order.

Not here, though. “Mr. Turner” is a mighty work of critical imagination, a loving, unsentimental portrait of a rare creative soul. But even as it celebrates a glorious painter and illuminates the sources of his pictures with startling clarity and insight, the movie patiently and thoroughly demolishes more than a century’s worth of mythology about what art is and how artists work. You may have had the good fortune to study Turner’s watercolors and martial tableaus up close, to linger over his storms and placid river scenes, but somehow Mr. Leigh makes it all look newly painted, fresh and strange.

Turner, played with blunt, brutish, grunting delicacy by Timothy Spall, is both a genius and an ordinary man, with the usual emotions and appetites. His art does not arise from any special torment or trauma, though he has his share of unhappiness. Nor is the unhappiness he inflicts on others — women in particular — excused as the prerogative of talent. The son of a barber, Turner takes a disciplined, businesslike, artisanal approach to his vocation, and even though he often seems gripped by an almost otherworldly inspiration, he and his art belong very much to the everyday world. With other artists, Turner is convivial, collegial and competitive. He is conscious of his celebrity, protective of his reputation and tireless in his labor.

It might be risking Ruskinesque folly to take “Mr. Turner” as a self-portrait of its director, but Turner shares with Mr. Leigh an ability to travel the circuit between the sublime and the ordinary, to bring into view aspects of reality that had been somehow invisible in plain sight. All of Mr. Leigh’s films are personal to the extent that they reflect his sensibility, his politics and his ethical concerns, but his methods — characters and stories developed over many months of rehearsal, improvisation and research in collaboration with actors and crew members — resist the imposition of a singular authorial vision. He is best known for anatomizing the pervasive indignities and saving graces of modern Britain, with particular attention to the low and middle rungs of the class ladder and the stresses and pleasures of family life. Social life for him is what sea air was to Turner: an atmospheric element that becomes a vehicle of meaning and emotion.

Mr. Leigh’s twin portraits of important 19th-century cultural figures (Gilbert and Sullivan in “Topsy-Turvy,” and now Turner in “Mr. Turner”) extend the range of his sympathy and curiosity into a past that is neither the mirror of the present nor wholly alien to the world as we know it. Turner, with his lumbering gait and broad, suety face, dominates the picture, seeming to personify his age and all its contradictions. His speech is a symphony of growls, snorts and flights of guttural eloquence. As he traipses from London to the seaside town of Margate and back, paces in his studio and prowls the galleries of the Royal Academy, we witness an act of creation that seems more sculptural than cinematic, as if Mr. Spall and Mr. Leigh were molding Turner in molten bronze.

At the same time, though, we might be reading a novel, a Victorian triple-decker thick with information about the organizing principles and deep contradictions of a complex civilization. We meet Turner in middle age, already successful and living with his cheerful father (Paul Jesson) and Hannah Danby (Dorothy Atkinson), a housekeeper whose patient, masochistic devotion is a source of occasional comedy and more frequent pathos.

Turner also has an angry, semi-estranged wife (Ruth Sheen) and two grown daughters (Sandy Foster and Amy Dawson), though when asked if he has children, he replies that he has none. On his visits to Margate, where he keeps amorous company with Sophia Booth (Marion Bailey), a kindhearted widow, he sheds his identity altogether, adopting his lady friend’s last name. The tenderness he shows her is missing from most of his relations with women, with the exception of Mary Somerville (Leslie Manville), a Scottish scientist who shares his interest in the properties of light.

Turner’s public life is no less complicated. He basks in the praise of critics and the envy of colleagues, and suffers when his work falls out of fashion, enduring overheard snark from the young Queen Victoria and mockery in a music hall sketch. He welcomes potential buyers and believes that his work should survive him as the property of the British people.

We not only see that work as it might have looked in its moment. We also, thanks to the exquisite, painterly cinematography of Dick Pope, see the world as Turner saw it. And as we do, an almost alchemical transformation takes place, as our various sensory and cognitive impressions merge into a thrilling and powerful form of understanding. By the end, we may not be able to summarize Turner’s life, explain his paintings or pass a midterm on British history. But we may find that our knowledge of all those things has deepened, and the compass by which we measure our own experience has grown wider. Only art can do that, and it may be all that art can do.

“Cynicism has no place in the reviewing of art.” Words to live by, for sure, and all the more so for being uttered by John Ruskin, one of the giants of 19th-century British art criticism. But nothing is quite so simple. In “Mr. Turner,” Mike Leigh’s revelatory new film, Ruskin (Joshua McGuire) appears as a pretentious carrot-topped nitwit with a voice like a posh Elmer Fudd. In one scene, he offers up “controversial” theories about landscapes and seascapes to a roomful of harrumphing artists. It’s all very well, one says, to opine and interpret, but unless you have braved the elements with brush in hand, you don’t really know what you’re talking about.

Fair enough. Though he and his parents are admirers and collectors of good paintings — and steadfast champions of the film’s hero, J. M. W. Turner — the Ruskin of Mr. Leigh’s film is a cruelly etched, cautionary figure, a warning that even those people most passionately devoted to the cause of art are likely to get it wrong. A bit of well-placed cynicism might even be in order.

Not here, though. “Mr. Turner” is a mighty work of critical imagination, a loving, unsentimental portrait of a rare creative soul. But even as it celebrates a glorious painter and illuminates the sources of his pictures with startling clarity and insight, the movie patiently and thoroughly demolishes more than a century’s worth of mythology about what art is and how artists work. You may have had the good fortune to study Turner’s watercolors and martial tableaus up close, to linger over his storms and placid river scenes, but somehow Mr. Leigh makes it all look newly painted, fresh and strange.

Turner, played with blunt, brutish, grunting delicacy by Timothy Spall, is both a genius and an ordinary man, with the usual emotions and appetites. His art does not arise from any special torment or trauma, though he has his share of unhappiness. Nor is the unhappiness he inflicts on others — women in particular — excused as the prerogative of talent. The son of a barber, Turner takes a disciplined, businesslike, artisanal approach to his vocation, and even though he often seems gripped by an almost otherworldly inspiration, he and his art belong very much to the everyday world. With other artists, Turner is convivial, collegial and competitive. He is conscious of his celebrity, protective of his reputation and tireless in his labor.

It might be risking Ruskinesque folly to take “Mr. Turner” as a self-portrait of its director, but Turner shares with Mr. Leigh an ability to travel the circuit between the sublime and the ordinary, to bring into view aspects of reality that had been somehow invisible in plain sight. All of Mr. Leigh’s films are personal to the extent that they reflect his sensibility, his politics and his ethical concerns, but his methods — characters and stories developed over many months of rehearsal, improvisation and research in collaboration with actors and crew members — resist the imposition of a singular authorial vision. He is best known for anatomizing the pervasive indignities and saving graces of modern Britain, with particular attention to the low and middle rungs of the class ladder and the stresses and pleasures of family life. Social life for him is what sea air was to Turner: an atmospheric element that becomes a vehicle of meaning and emotion.

Mr. Leigh’s twin portraits of important 19th-century cultural figures (Gilbert and Sullivan in “Topsy-Turvy,” and now Turner in “Mr. Turner”) extend the range of his sympathy and curiosity into a past that is neither the mirror of the present nor wholly alien to the world as we know it. Turner, with his lumbering gait and broad, suety face, dominates the picture, seeming to personify his age and all its contradictions. His speech is a symphony of growls, snorts and flights of guttural eloquence. As he traipses from London to the seaside town of Margate and back, paces in his studio and prowls the galleries of the Royal Academy, we witness an act of creation that seems more sculptural than cinematic, as if Mr. Spall and Mr. Leigh were molding Turner in molten bronze.

At the same time, though, we might be reading a novel, a Victorian triple-decker thick with information about the organizing principles and deep contradictions of a complex civilization. We meet Turner in middle age, already successful and living with his cheerful father (Paul Jesson) and Hannah Danby (Dorothy Atkinson), a housekeeper whose patient, masochistic devotion is a source of occasional comedy and more frequent pathos.

Turner also has an angry, semi-estranged wife (Ruth Sheen) and two grown daughters (Sandy Foster and Amy Dawson), though when asked if he has children, he replies that he has none. On his visits to Margate, where he keeps amorous company with Sophia Booth (Marion Bailey), a kindhearted widow, he sheds his identity altogether, adopting his lady friend’s last name. The tenderness he shows her is missing from most of his relations with women, with the exception of Mary Somerville (Leslie Manville), a Scottish scientist who shares his interest in the properties of light.

Turner’s public life is no less complicated. He basks in the praise of critics and the envy of colleagues, and suffers when his work falls out of fashion, enduring overheard snark from the young Queen Victoria and mockery in a music hall sketch. He welcomes potential buyers and believes that his work should survive him as the property of the British people.

We not only see that work as it might have looked in its moment. We also, thanks to the exquisite, painterly cinematography of Dick Pope, see the world as Turner saw it. And as we do, an almost alchemical transformation takes place, as our various sensory and cognitive impressions merge into a thrilling and powerful form of understanding. By the end, we may not be able to summarize Turner’s life, explain his paintings or pass a midterm on British history. But we may find that our knowledge of all those things has deepened, and the compass by which we measure our own experience has grown wider. Only art can do that, and it may be all that art can do.