“Knocks the wind right out of you and lingers in your mind for days.”

NEW YORK POST

“Intense, moving and thought-provoking.”

DEADLINE

“By the end you’ll feel you touched the core of something real.”

VARIETY

NEW YORK POST

“Intense, moving and thought-provoking.”

DEADLINE

“By the end you’ll feel you touched the core of something real.”

VARIETY

CAST & CREW

Directed by Fran Kranz

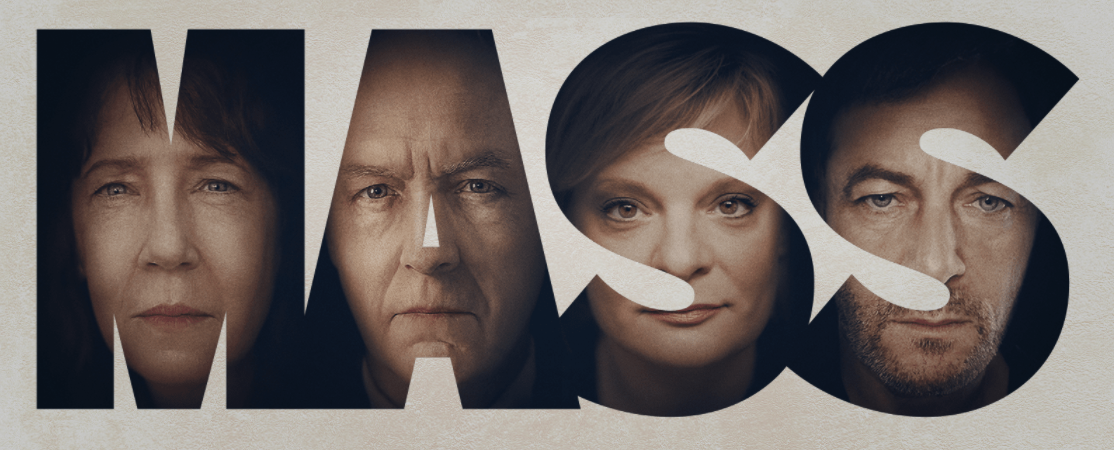

Featuring Reed Birney, Ann Dowd, Jason Isaac, Martha Plimpton

Rated PG-13 | Running Time: 111 min

Directed by Fran Kranz

Featuring Reed Birney, Ann Dowd, Jason Isaac, Martha Plimpton

Rated PG-13 | Running Time: 111 min

Ann Hornaday | Washington Post

In a sparsely appointed meeting room of an Episcopal church somewhere out West, two couples gather, doffing overcoats and making small talk. The mood is wary, tense. They sit. And in the conversation that ensues — as the point of their encounter becomes clear — what begins as an impressive exercise in acting and character development assumes the contours of something bigger, more seismic and emotionally shattering.

“Mass” marks the writing-directing debut of actor Fran Kranz, who brings a tasteful and judicious eye to a project that could be easily sundered by melodrama and opportunism. It turns out that Gail and Jay (Martha Plimpton and Jason Isaacs) have agreed to meet with Linda and Richard (Ann Dowd and Reed Birney) to discuss a school shooting that transpired six years earlier. Each couple lost a son in the tragedy, and all are being haunted, in some way, by denial, guilt, rage and unresolved grief.

Kranz doles out information with such care and thoughtfulness in “Mass” that more precise descriptions don’t do the film justice: As the confrontation plays out in real time, viewers become privy to the distinct, often diametrically opposed, perspectives of the participants. Plimpton’s Gail, a spiky combination of simmering anger and raw pain, seems to be the polar opposite of Dowd’s Linda, who has clearly done more interior work toward healing and understanding. Isaacs’s Jay has processed his loss by throwing himself into action and activism, which bears more than a little resemblance to the task-oriented conventionality of Birney’s Richard.

Those descriptions fit up to a point, at least until these complex, sometimes contradictory characters begin to shed their defensive layers. What makes “Mass” such an absorbing and ultimately moving film is the way Kranz constantly goes deeper, his spare, unadorned visual language allowing words and behavior — channeled through four extraordinarily brave performances — to do their revelatory work. Although it’s true that “Mass” resembles a theater piece in its style and structure, it takes cinema to bore into peoples’ most tender psyches with such intensity; similar in some ways to Yasmina Reza’s 2008 play “God of Carnage,” Kranz approaches his portrait of moral injury and its sequelae with a carefully calibrated mix of ruthlessness and compassion.

With the help of his outstanding ensemble — each of whom delivers a breathtaking performance in his or her own right — Kranz also punctures the misapprehension that the practice of restorative justice, which focuses on healing, accountability and meaningful restitution, is less rigorous or demanding than the traditional adversarial system of punishment and retribution. As the conversation in “Mass” reaches its cathartic climax, it becomes clear just how agonizing it is to stay in the room, despite every impulse to seek comfort in the resentments, beliefs and self-flagellation that the characters have resorted to for solace.

Reportedly, Kranz considered several titles before settling on “Mass,” which can be interpreted in myriad ways: On its surface, the film asks if forgiveness is possible in the wake of unspeakable injustice and violence. At its core, “Mass” exerts the power of ritual at its most reflective and galvanizing, reveling in human connection at its most arduous, persistent and sublime.

In a sparsely appointed meeting room of an Episcopal church somewhere out West, two couples gather, doffing overcoats and making small talk. The mood is wary, tense. They sit. And in the conversation that ensues — as the point of their encounter becomes clear — what begins as an impressive exercise in acting and character development assumes the contours of something bigger, more seismic and emotionally shattering.

“Mass” marks the writing-directing debut of actor Fran Kranz, who brings a tasteful and judicious eye to a project that could be easily sundered by melodrama and opportunism. It turns out that Gail and Jay (Martha Plimpton and Jason Isaacs) have agreed to meet with Linda and Richard (Ann Dowd and Reed Birney) to discuss a school shooting that transpired six years earlier. Each couple lost a son in the tragedy, and all are being haunted, in some way, by denial, guilt, rage and unresolved grief.

Kranz doles out information with such care and thoughtfulness in “Mass” that more precise descriptions don’t do the film justice: As the confrontation plays out in real time, viewers become privy to the distinct, often diametrically opposed, perspectives of the participants. Plimpton’s Gail, a spiky combination of simmering anger and raw pain, seems to be the polar opposite of Dowd’s Linda, who has clearly done more interior work toward healing and understanding. Isaacs’s Jay has processed his loss by throwing himself into action and activism, which bears more than a little resemblance to the task-oriented conventionality of Birney’s Richard.

Those descriptions fit up to a point, at least until these complex, sometimes contradictory characters begin to shed their defensive layers. What makes “Mass” such an absorbing and ultimately moving film is the way Kranz constantly goes deeper, his spare, unadorned visual language allowing words and behavior — channeled through four extraordinarily brave performances — to do their revelatory work. Although it’s true that “Mass” resembles a theater piece in its style and structure, it takes cinema to bore into peoples’ most tender psyches with such intensity; similar in some ways to Yasmina Reza’s 2008 play “God of Carnage,” Kranz approaches his portrait of moral injury and its sequelae with a carefully calibrated mix of ruthlessness and compassion.

With the help of his outstanding ensemble — each of whom delivers a breathtaking performance in his or her own right — Kranz also punctures the misapprehension that the practice of restorative justice, which focuses on healing, accountability and meaningful restitution, is less rigorous or demanding than the traditional adversarial system of punishment and retribution. As the conversation in “Mass” reaches its cathartic climax, it becomes clear just how agonizing it is to stay in the room, despite every impulse to seek comfort in the resentments, beliefs and self-flagellation that the characters have resorted to for solace.

Reportedly, Kranz considered several titles before settling on “Mass,” which can be interpreted in myriad ways: On its surface, the film asks if forgiveness is possible in the wake of unspeakable injustice and violence. At its core, “Mass” exerts the power of ritual at its most reflective and galvanizing, reveling in human connection at its most arduous, persistent and sublime.