Reviewed by Peter Debruge – Variety

Cover your ears and open your hearts: In French director Xavier Giannoli’s pitch-perfect comedy of manners, “Marguerite,” a shameless chanteuse with a surplus of money and a shortage of talent buys her way into the spotlight, exposing the hypocrisy of her unctuous social circle in the process. Inspired by screechy American soprano Florence Foster Jenkins — the selfsame warbler soon to be embodied by Meryl Streep in a forthcoming Stephen Frears biopic — this splendid satire benefits not only from being the first to reach the screen, but also from “The Singer” director Giannoli’s gift for striking just the right tone with such tricky material.

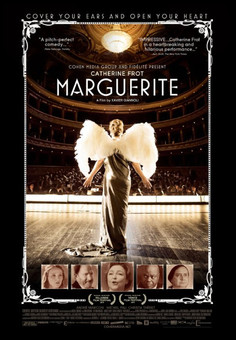

Time will tell what approach Frears’ version will take, though this competing project, starring Cesar-winning French chameleon Catherine Frot (whose awards record ain’t so shabby next to Streep’s), presents the ridiculous baroness in such a way that we laugh at her strangled ululations, but not the fragile soul responsible. In another director’s hands, Marguerite Dumont — whose fictitious moniker sounds an awful lot like the Marx Brothers’ matriarchal foil — might have been easily reduced to the butt of a cruel joke, as Jenkins was in several stage plays, including “Souvenir” and “Glorious!” But Giannoli approaches Marguerite with sympathy, casting Frot for her ability to bring out the character’s human side.

In the decades since her death (tellingly, one month after a career-ending 1944 concert at Carnegie Hall), Marguerite’s real-life model hasn’t been so fortunate: Jenkins’ notoriously horrendous voice lives on today in the form of novelty records, and one need only search her name on YouTube to hear the tone-deaf soprano mauling Mozart’s “Queen of the Night” — an impossibly difficult aria that demands a properly trained coloratura to navigate its tricky arpeggio minefield and capture that high-F flag. Naturally, this is the same song Marguerite selects to perform in the film’s opening number.

Giannoli sets the scene by following the arrival of a nervous young music student at the Dumont estate (mousily played by Christa Theret, whose subplot barely survives a film that’s arguably overlong as-is). The unsuspecting girl has been hired to sing a duet at a benefit for war orphans hosted by Marguerite herself, where this enigmatic aristocratic (who fussily prepares herself upstairs and offcamera) will be the main attraction. Meanwhile, determined to hear her voice for themselves, two young men — one a journalist (Sylvain Dieuaide), the other a self-styled anarchist (Aubert Fenoy) — scale the wall and sneak into the recital.

Like Jenkins, Marguerite restricts her concerts to a by-invitation-only audience of sycophantic acquaintances, who offer nothing but compliments to her face, while whispering insults behind her back. As the anticipation mounts, her husband (Andre Marcon) invents an excuse not to attend by faking the breakdown of his gorgeous Sima-Standard automobile, clearly determined to avoid the embarrassment — a view counterbalanced by Marguerite’s over-protective butler, Madelbos (Denis Mpunga), who personally encourages her fantasy, even going so far as to photograph his employer in campy secondhand opera costumes.

And so, with all ears on her, Marguerite descends, the music starts … and the manor’s chandeliers tremble in fear of her crystal-shattering trills. While the theater audience can’t help but chuckle, the assembled guests are held prisoner by her caterwauling — players in a sort of modern-day “Emperor’s New Clothes,” wherein no one has the courage to tell Marguerite the truth. That dynamic grows even more heightened later when Madelbos blackmails an insolvent opera star (played as a limelight-loving fop by Michel Fau, who milks the role for maximum drama) into giving her voice lessons.

The day after her war-orphan debacle, Marguerite is overwhelmed by a double-edged “rave” in the party-crashing reporter’s paper and a parlor full of white flowers from her “admirers.” (Like the elegant lady that she is, Marguerite favors all things alabaster, giving the film its tony, almost-monochrome aesthetic.) She opts to take these tokens at face value, though Giannoli deliciously implies that they are not what they seem: Madelbos discreetly clips the crueler reviews from the Paris broadsheets so Marguerite won’t see them, exchanging knowing looks with the baron that suggest he was the one to have ordered the flowers.

While “Marguerite” is first and foremost the fable of a woman so smitten with music (and later, by the thrill of an audience) that she feels compelled to practice it well beyond the all-too-evident limits of her own ability, Giannoli’s script encompasses multiple love stories in one. Less cynical than “Superstar,” but not quite as sensitive as “The Singer” (his underseen 2006 romance, in which a talented musician is reduced to working as a lounge singer), the film also explores the marital dynamic between Marguerite and her opportunistic husband, who tells his mistress that “she bought my title, not me,” but gradually comes to redeem himself.

More moving still is the way Madelbos treats Marguerite, cueing the audience as to how they should view her as well: with empathy and patience. Though he occasionally fades into the woodwork (or else stands out a bit too prominently, as in one jarring sex scene), Madelbos quietly enables — one might even say “orchestrates” — Marguerite’s fantasy. Congolese actor Mpunga plays the subtext as needed, underscoring the film’s exquisite class commentary in the process. Just as last year’s “Foxcatcher” dared to expose the ugliness of America’s oligarchical tendencies, “Marguerite” skewers France’s two-faced upper crust, where sincerity seems a foreign concept and money can buy neither taste nor talent.

Jenkins, who was rendered partly deaf by syphilis, dismissed the haters who dared to criticize her singing, whereas Marguerite is too naive to even realize she’s awful — leading to a rather awkward “they’re all gonna laugh at you” montage in the film’s finale. At her faux-friends’ urging, Marguerite takes to the stage wearing a pair of feathered wings. Like nearly every detail that might seem “too much,” this costume hails from Jenkins’ life. If anything, it’s in the emotionally sincere bits that Giannoli has allowed himself a certain amount of dramatic license.

The helmer, who has been featured twice in competition at Cannes, is a maestro when it comes to the classical aspects of the medium, employing production design, costumes and props to their utmost potential, while heightening our involvement through strategic use of music and mise-en-scene. If Marguerite’s climactic public concert feels bathetic — the ugly duckling to “Black Swan’s” all-or-nothing curtain call — that’s only because her folly doesn’t end there. It’s the poetic epilogue that follows in which Marguerite’s fate shall be decided, while we are left to interpret whether her acoustic hubris ultimately destroyed her life or saved her marriage.

A DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

Cover your ears and open your hearts: In French director Xavier Giannoli’s pitch-perfect comedy of manners, “Marguerite,” a shameless chanteuse with a surplus of money and a shortage of talent buys her way into the spotlight, exposing the hypocrisy of her unctuous social circle in the process. Inspired by screechy American soprano Florence Foster Jenkins — the selfsame warbler soon to be embodied by Meryl Streep in a forthcoming Stephen Frears biopic — this splendid satire benefits not only from being the first to reach the screen, but also from “The Singer” director Giannoli’s gift for striking just the right tone with such tricky material.

Time will tell what approach Frears’ version will take, though this competing project, starring Cesar-winning French chameleon Catherine Frot (whose awards record ain’t so shabby next to Streep’s), presents the ridiculous baroness in such a way that we laugh at her strangled ululations, but not the fragile soul responsible. In another director’s hands, Marguerite Dumont — whose fictitious moniker sounds an awful lot like the Marx Brothers’ matriarchal foil — might have been easily reduced to the butt of a cruel joke, as Jenkins was in several stage plays, including “Souvenir” and “Glorious!” But Giannoli approaches Marguerite with sympathy, casting Frot for her ability to bring out the character’s human side.

In the decades since her death (tellingly, one month after a career-ending 1944 concert at Carnegie Hall), Marguerite’s real-life model hasn’t been so fortunate: Jenkins’ notoriously horrendous voice lives on today in the form of novelty records, and one need only search her name on YouTube to hear the tone-deaf soprano mauling Mozart’s “Queen of the Night” — an impossibly difficult aria that demands a properly trained coloratura to navigate its tricky arpeggio minefield and capture that high-F flag. Naturally, this is the same song Marguerite selects to perform in the film’s opening number.

Giannoli sets the scene by following the arrival of a nervous young music student at the Dumont estate (mousily played by Christa Theret, whose subplot barely survives a film that’s arguably overlong as-is). The unsuspecting girl has been hired to sing a duet at a benefit for war orphans hosted by Marguerite herself, where this enigmatic aristocratic (who fussily prepares herself upstairs and offcamera) will be the main attraction. Meanwhile, determined to hear her voice for themselves, two young men — one a journalist (Sylvain Dieuaide), the other a self-styled anarchist (Aubert Fenoy) — scale the wall and sneak into the recital.

Like Jenkins, Marguerite restricts her concerts to a by-invitation-only audience of sycophantic acquaintances, who offer nothing but compliments to her face, while whispering insults behind her back. As the anticipation mounts, her husband (Andre Marcon) invents an excuse not to attend by faking the breakdown of his gorgeous Sima-Standard automobile, clearly determined to avoid the embarrassment — a view counterbalanced by Marguerite’s over-protective butler, Madelbos (Denis Mpunga), who personally encourages her fantasy, even going so far as to photograph his employer in campy secondhand opera costumes.

And so, with all ears on her, Marguerite descends, the music starts … and the manor’s chandeliers tremble in fear of her crystal-shattering trills. While the theater audience can’t help but chuckle, the assembled guests are held prisoner by her caterwauling — players in a sort of modern-day “Emperor’s New Clothes,” wherein no one has the courage to tell Marguerite the truth. That dynamic grows even more heightened later when Madelbos blackmails an insolvent opera star (played as a limelight-loving fop by Michel Fau, who milks the role for maximum drama) into giving her voice lessons.

The day after her war-orphan debacle, Marguerite is overwhelmed by a double-edged “rave” in the party-crashing reporter’s paper and a parlor full of white flowers from her “admirers.” (Like the elegant lady that she is, Marguerite favors all things alabaster, giving the film its tony, almost-monochrome aesthetic.) She opts to take these tokens at face value, though Giannoli deliciously implies that they are not what they seem: Madelbos discreetly clips the crueler reviews from the Paris broadsheets so Marguerite won’t see them, exchanging knowing looks with the baron that suggest he was the one to have ordered the flowers.

While “Marguerite” is first and foremost the fable of a woman so smitten with music (and later, by the thrill of an audience) that she feels compelled to practice it well beyond the all-too-evident limits of her own ability, Giannoli’s script encompasses multiple love stories in one. Less cynical than “Superstar,” but not quite as sensitive as “The Singer” (his underseen 2006 romance, in which a talented musician is reduced to working as a lounge singer), the film also explores the marital dynamic between Marguerite and her opportunistic husband, who tells his mistress that “she bought my title, not me,” but gradually comes to redeem himself.

More moving still is the way Madelbos treats Marguerite, cueing the audience as to how they should view her as well: with empathy and patience. Though he occasionally fades into the woodwork (or else stands out a bit too prominently, as in one jarring sex scene), Madelbos quietly enables — one might even say “orchestrates” — Marguerite’s fantasy. Congolese actor Mpunga plays the subtext as needed, underscoring the film’s exquisite class commentary in the process. Just as last year’s “Foxcatcher” dared to expose the ugliness of America’s oligarchical tendencies, “Marguerite” skewers France’s two-faced upper crust, where sincerity seems a foreign concept and money can buy neither taste nor talent.

Jenkins, who was rendered partly deaf by syphilis, dismissed the haters who dared to criticize her singing, whereas Marguerite is too naive to even realize she’s awful — leading to a rather awkward “they’re all gonna laugh at you” montage in the film’s finale. At her faux-friends’ urging, Marguerite takes to the stage wearing a pair of feathered wings. Like nearly every detail that might seem “too much,” this costume hails from Jenkins’ life. If anything, it’s in the emotionally sincere bits that Giannoli has allowed himself a certain amount of dramatic license.

The helmer, who has been featured twice in competition at Cannes, is a maestro when it comes to the classical aspects of the medium, employing production design, costumes and props to their utmost potential, while heightening our involvement through strategic use of music and mise-en-scene. If Marguerite’s climactic public concert feels bathetic — the ugly duckling to “Black Swan’s” all-or-nothing curtain call — that’s only because her folly doesn’t end there. It’s the poetic epilogue that follows in which Marguerite’s fate shall be decided, while we are left to interpret whether her acoustic hubris ultimately destroyed her life or saved her marriage.

A DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members