Reviewed by Geoffrey O'Brien--New York Times

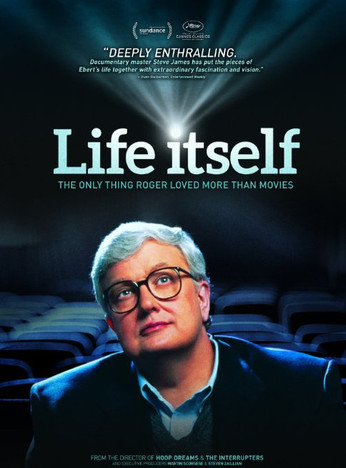

“Life Itself,” Steve James’s documentary on the life of Roger Ebert, is in many ways like a wake at which intimate acquaintances warmly recall their departed friend in all his aspects, foibles and quirks along with his talents and triumphs. Deep currents of love and sorrow flow under the succession of often funny recollections of a busy life. But it is a wake where the departed is still present.

This is not only a film about Roger Ebert but also a film very much with and by Roger Ebert, who was the most famous and affectionately regarded of American movie critics, the Pulitzer Prize-winning reviewer for The Chicago Sun-Times who, in company with Gene Siskel, improbably became a globally known television star, and who refused to be laid low by the medical catastrophes of his last years. A friend describes him as having been, early on, “not just the chief character and star of the movie that was his life, he was also the director.” “Life Itself” is indeed broadly shaped by Ebert’s own interpretation of his life and clearly marked by his sense of what kind of film it should be.

At a crucial point, as the extent of his latest (and, as it turned out, final) medical crisis emerges, he sends an email urging Mr. James to be frank in his depiction, reminding him, “This is not only your film.” Even after years of dealing with a cancer whose treatment disfigured him and deprived him of the ability to eat, drink or speak, he remained a forceful presence — perhaps more forceful than he had ever been. On camera, his jaw gone, communicating ceaselessly by voice synthesizer or handwritten notes or gestures, he holds us with the depth of awareness in his eyes, as if he remained the alert spectator he had always been, not missing a moment of a spectacle from which he had no desire to retreat: “This is the third act,” he wrote, “and it is an experience.”

The film began as a proposed adaptation of Ebert’s 2011 memoir of the same title, a self-portrait whose calm and open tone is the more remarkable for the circumstances under which it was written. Mr. James — whose own career was buoyed by his subject’s early praise for his documentary “Hoop Dreams” — first met with Ebert and his wife, Chaz, five months before Ebert’s death in April of last year. He had hoped to track Ebert as he continued to lead his determinedly productive life as critic and commentator, both in print and on the social media in which he had become a major presence.

Ebert’s condition deteriorated just before shooting began, so what Mr. James ended up filming were scenes of a hospital and a rehab center, culminating in some extraordinarily raw moments of pain, uncertainty, exhaustion and grief. Any sense of intrusion is mitigated by the feeling that Ebert’s intent is being honored, up to the point where he acknowledges his inability to go on in a terse last email to the director: “i can’t.”

As these scenes unfold, a parallel narrative takes us through Ebert’s past. An actor reads passages from the memoir while we are shown countless artifacts of a well-documented life: the hectographed newspaper he produced himself while still in grade school in Urbana, Ill.; a powerful political editorial from the college paper he edited; his own pen-and-ink drawings of the Cannes Film Festival. Excerpts from Ebert’s film reviews are accompanied by clips from movies important to him — from “Bonnie and Clyde” to “The Tree of Life” — figuring not as milestones of film history but as scenes from his life, peak experiences that prompted eloquent writing.

Ebert’s words are joined by those of many others: filmmaker friends like Martin Scorsese and Werner Herzog, and old acquaintances whose deep fondness is apparent but who don’t gloss over his complications and confusions, from his outwardly rowdy days hanging out at O’Rourke’s in Chicago (he stopped drinking in the late ’70s) to the defensive petulance sometimes provoked by Siskel during their on-air critical brawls. (“He is a nice guy,” one friend smilingly comments, “but he’s not that nice.”) There is a rich aura of journalistic camaraderie and Chicago solidarity. When The Washington Post’s editors tried to lure him away with a big-money offer, Ebert told them, “I’m not gonna learn new streets.”

Ebert was often described as egalitarian and populist in his approach to movies and life. “Life Itself” opens by citing his definition of cinema as “a machine that generates empathy,” and he was not interested in rarefied or exclusionary approaches to aesthetics. Even if he was writing about Bergman or Bresson, he was writing for the widest possible readership. Yet, as A. O. Scott of The New York Times comments, he never pandered or condescended.

As we apprehend Ebert through the testimony given here, it becomes clear that his abilities were prodigious — a natural writer, he could, by one account, “knock out a full thought-out movie review in 30 minutes” — and his personality more than a little eccentrically uncommon. There are glimpses of depression and loneliness withheld from public view and of a controlling temperament that met its match when he was teamed with Siskel, of The Chicago Tribune, for a local show that finally made them both stars.

“Gene,” an observer notes, “was a rogue planet in Roger’s solar system.” Shouting matches and withering put-downs were hallmarks of their show — critical argument became comic performance art — but the tensions were real enough. When Ebert yells, “I disagree particularly about the part you like!,” it is almost like intruding on a family argument. A series of outtakes in which they trade insults between fluffed lines is both hilarious and a bit harrowing. Interpersonal dynamics (and eye-popping ’70s fashions) aside, the frustratingly brief clips shown here provoke an appetite for more.

“Life Itself” is a work of deftness and delicacy, by turns a film about illness and death, about writing, about cinema and, finally, and very movingly a film about love. Ebert was, by his own and others’ accounts, transformed by meeting and marrying Chaz when he was 50. She was an African-American civil rights lawyer more interested, as he put it, in who he was than in what he did. He became part of her extended family, and as we watch him in home videos from the good days before his troubles started, it is like watching a man blossoming before our eyes.

It cannot have been easy for Chaz Ebert to be filmed at a time of the most extreme vulnerability. With her wrenching account of his last days — “He was beginning to feel trapped inside” — we are at last unavoidably caught up face to face with the absence that even the liveliest of wakes must finally acknowledge.

“Life Itself,” Steve James’s documentary on the life of Roger Ebert, is in many ways like a wake at which intimate acquaintances warmly recall their departed friend in all his aspects, foibles and quirks along with his talents and triumphs. Deep currents of love and sorrow flow under the succession of often funny recollections of a busy life. But it is a wake where the departed is still present.

This is not only a film about Roger Ebert but also a film very much with and by Roger Ebert, who was the most famous and affectionately regarded of American movie critics, the Pulitzer Prize-winning reviewer for The Chicago Sun-Times who, in company with Gene Siskel, improbably became a globally known television star, and who refused to be laid low by the medical catastrophes of his last years. A friend describes him as having been, early on, “not just the chief character and star of the movie that was his life, he was also the director.” “Life Itself” is indeed broadly shaped by Ebert’s own interpretation of his life and clearly marked by his sense of what kind of film it should be.

At a crucial point, as the extent of his latest (and, as it turned out, final) medical crisis emerges, he sends an email urging Mr. James to be frank in his depiction, reminding him, “This is not only your film.” Even after years of dealing with a cancer whose treatment disfigured him and deprived him of the ability to eat, drink or speak, he remained a forceful presence — perhaps more forceful than he had ever been. On camera, his jaw gone, communicating ceaselessly by voice synthesizer or handwritten notes or gestures, he holds us with the depth of awareness in his eyes, as if he remained the alert spectator he had always been, not missing a moment of a spectacle from which he had no desire to retreat: “This is the third act,” he wrote, “and it is an experience.”

The film began as a proposed adaptation of Ebert’s 2011 memoir of the same title, a self-portrait whose calm and open tone is the more remarkable for the circumstances under which it was written. Mr. James — whose own career was buoyed by his subject’s early praise for his documentary “Hoop Dreams” — first met with Ebert and his wife, Chaz, five months before Ebert’s death in April of last year. He had hoped to track Ebert as he continued to lead his determinedly productive life as critic and commentator, both in print and on the social media in which he had become a major presence.

Ebert’s condition deteriorated just before shooting began, so what Mr. James ended up filming were scenes of a hospital and a rehab center, culminating in some extraordinarily raw moments of pain, uncertainty, exhaustion and grief. Any sense of intrusion is mitigated by the feeling that Ebert’s intent is being honored, up to the point where he acknowledges his inability to go on in a terse last email to the director: “i can’t.”

As these scenes unfold, a parallel narrative takes us through Ebert’s past. An actor reads passages from the memoir while we are shown countless artifacts of a well-documented life: the hectographed newspaper he produced himself while still in grade school in Urbana, Ill.; a powerful political editorial from the college paper he edited; his own pen-and-ink drawings of the Cannes Film Festival. Excerpts from Ebert’s film reviews are accompanied by clips from movies important to him — from “Bonnie and Clyde” to “The Tree of Life” — figuring not as milestones of film history but as scenes from his life, peak experiences that prompted eloquent writing.

Ebert’s words are joined by those of many others: filmmaker friends like Martin Scorsese and Werner Herzog, and old acquaintances whose deep fondness is apparent but who don’t gloss over his complications and confusions, from his outwardly rowdy days hanging out at O’Rourke’s in Chicago (he stopped drinking in the late ’70s) to the defensive petulance sometimes provoked by Siskel during their on-air critical brawls. (“He is a nice guy,” one friend smilingly comments, “but he’s not that nice.”) There is a rich aura of journalistic camaraderie and Chicago solidarity. When The Washington Post’s editors tried to lure him away with a big-money offer, Ebert told them, “I’m not gonna learn new streets.”

Ebert was often described as egalitarian and populist in his approach to movies and life. “Life Itself” opens by citing his definition of cinema as “a machine that generates empathy,” and he was not interested in rarefied or exclusionary approaches to aesthetics. Even if he was writing about Bergman or Bresson, he was writing for the widest possible readership. Yet, as A. O. Scott of The New York Times comments, he never pandered or condescended.

As we apprehend Ebert through the testimony given here, it becomes clear that his abilities were prodigious — a natural writer, he could, by one account, “knock out a full thought-out movie review in 30 minutes” — and his personality more than a little eccentrically uncommon. There are glimpses of depression and loneliness withheld from public view and of a controlling temperament that met its match when he was teamed with Siskel, of The Chicago Tribune, for a local show that finally made them both stars.

“Gene,” an observer notes, “was a rogue planet in Roger’s solar system.” Shouting matches and withering put-downs were hallmarks of their show — critical argument became comic performance art — but the tensions were real enough. When Ebert yells, “I disagree particularly about the part you like!,” it is almost like intruding on a family argument. A series of outtakes in which they trade insults between fluffed lines is both hilarious and a bit harrowing. Interpersonal dynamics (and eye-popping ’70s fashions) aside, the frustratingly brief clips shown here provoke an appetite for more.

“Life Itself” is a work of deftness and delicacy, by turns a film about illness and death, about writing, about cinema and, finally, and very movingly a film about love. Ebert was, by his own and others’ accounts, transformed by meeting and marrying Chaz when he was 50. She was an African-American civil rights lawyer more interested, as he put it, in who he was than in what he did. He became part of her extended family, and as we watch him in home videos from the good days before his troubles started, it is like watching a man blossoming before our eyes.

It cannot have been easy for Chaz Ebert to be filmed at a time of the most extreme vulnerability. With her wrenching account of his last days — “He was beginning to feel trapped inside” — we are at last unavoidably caught up face to face with the absence that even the liveliest of wakes must finally acknowledge.