Reviewed by MoiraMacdonald / Seattle Times

The art of Andy Goldsworthy is not about the complex systems of the natural world. Instead, it’s in collaboration with them. Goldsworthy’s projects — in the woods of Scotland, the streets of Edinburgh, the cliffs of Gabon — often flow from those systems and then are destroyed by them. Witness him layering gold-yellow leaves he’s gathered across the faces of black rocks on a hillside, only to see the wind tear his work away before he’s finished. Watch him create his Rain Shadows: He lies flat on his back on an outcrop or sidewalk as the rain or snow starts, and then stands some moments later, leaving behind a patch of dry silhouette that quickly, beautifully, darkens from the precipitation. The work lasts for a breath, maybe two.

In the first scene of Leaning Into the Wind, the follow-up to 2001’s Rivers and Tides: Andy Goldsworthy Working With Time, Goldsworthy, now sixty, makes his way, with awed solemnity, through an abandoned stone home in Brazil’s Ibitipoca Reserve. A shaft of sunlight beams down through a hole in the ceiling of an otherwise dark back room. The artist scoops dust from the earthen floor and tosses it into the light. It billows and clouds. He reaches into the beam, breaking it, and then pulls his hand back. He repeats this, again and again, faster and faster, strobing the sun. Director Thomas Riedelsheimer then employs a four-way split screen, showing Goldsworthy’s protracted engagement with the light, his zeal to discover every interesting interaction he could have with it. It’s art but also play and even dance. Then, this being the restlessly curious Goldsworthy, the film soon cuts to the English artist and his local guides interviewing locals in a similar home about their clay floors, about how they built something so smooth and strong upon the soil yet from the soil.

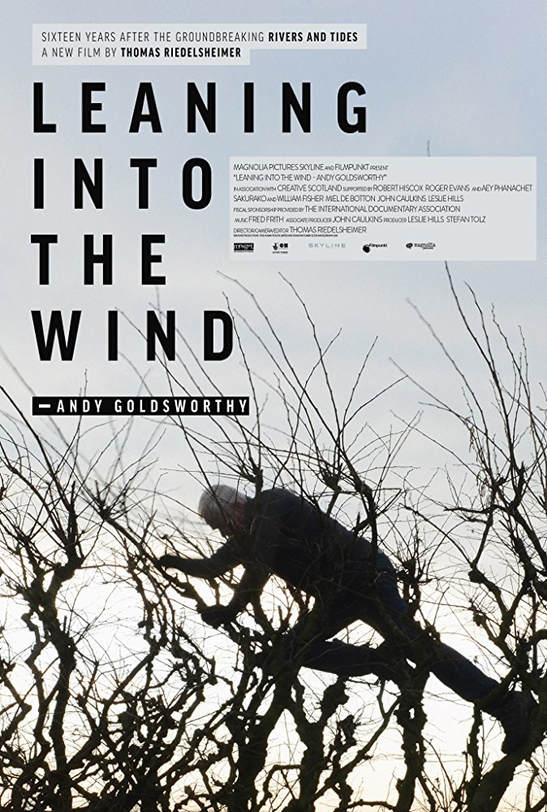

Like Rivers and Tides, also directed by Riedelsheimer, Leaning Into the Wind is a study in seeing, in subordinating one’s self to the elements, in creating with nature rather than from it. (Fred Frith once again furnishes a score.) The film ranges more widely than its predecessor, surveying more landscapes and a greater variety of projects. But it’s still a contemplative beauty, a chance to consider and be moved by a richer sort of connectedness than our lives typically allow. Goldsworthy steeps himself in forests and streams, creating sculpture from driftwood or stones, works that honor the flow of the elements around them — and will eventually be overwhelmed by them.

Goldsworthy has created some permanent works, which we see in the film, but even these are built with humility. Late in the documentary, he apologizes to the crew because he just can’t bring himself to perform the work he had planned for the morning — drill into bedrock. He does subtly alter some landscapes: Inspired by the remains of stone walls built long ago by the first farmers in New England, Goldsworthy splits native boulders in two and then carves a path between them. Much of the work is purely ephemeral, with the film and Goldsworthy’s photographs our only record of it: He and his daughter/assistant wrap his finger and hands in ruby-red flower petals, creating an alien skin. He then dips each hand into a stream, the current tugging the petals away. They parade along with the flow.

One permanent work involves a canvas and could even be hung in a gallery. But here Goldsworthy’s collaborator is sheep: He and his daughter lay a white canvas out in a muddy pasture and then set a bucket of feed in the center. Soon, the flock comes to eat. The completed work, all brown hoofprints, charts the patterns of their milling, making a study of the instinctual choices of livestock. At the center of this muddy study: a circle of white where the bucket had stood.

The title comes from Goldsworthy’s own efforts to get himself fully into the flow of systems indifferent to us. In England, during a windstorm, he stands upon a grassy bluff and faces the gusts, outstretching his hands, leaning his body forward. He stumbles back and forth, sometimes in danger of tumbling over the precipice. The winds batter him backward. But sometimes, for a heartbeat, he’s held there, standing at an almost 45 degree angle, buffeted and supported at one. It’s a dance.

The art of Andy Goldsworthy is not about the complex systems of the natural world. Instead, it’s in collaboration with them. Goldsworthy’s projects — in the woods of Scotland, the streets of Edinburgh, the cliffs of Gabon — often flow from those systems and then are destroyed by them. Witness him layering gold-yellow leaves he’s gathered across the faces of black rocks on a hillside, only to see the wind tear his work away before he’s finished. Watch him create his Rain Shadows: He lies flat on his back on an outcrop or sidewalk as the rain or snow starts, and then stands some moments later, leaving behind a patch of dry silhouette that quickly, beautifully, darkens from the precipitation. The work lasts for a breath, maybe two.

In the first scene of Leaning Into the Wind, the follow-up to 2001’s Rivers and Tides: Andy Goldsworthy Working With Time, Goldsworthy, now sixty, makes his way, with awed solemnity, through an abandoned stone home in Brazil’s Ibitipoca Reserve. A shaft of sunlight beams down through a hole in the ceiling of an otherwise dark back room. The artist scoops dust from the earthen floor and tosses it into the light. It billows and clouds. He reaches into the beam, breaking it, and then pulls his hand back. He repeats this, again and again, faster and faster, strobing the sun. Director Thomas Riedelsheimer then employs a four-way split screen, showing Goldsworthy’s protracted engagement with the light, his zeal to discover every interesting interaction he could have with it. It’s art but also play and even dance. Then, this being the restlessly curious Goldsworthy, the film soon cuts to the English artist and his local guides interviewing locals in a similar home about their clay floors, about how they built something so smooth and strong upon the soil yet from the soil.

Like Rivers and Tides, also directed by Riedelsheimer, Leaning Into the Wind is a study in seeing, in subordinating one’s self to the elements, in creating with nature rather than from it. (Fred Frith once again furnishes a score.) The film ranges more widely than its predecessor, surveying more landscapes and a greater variety of projects. But it’s still a contemplative beauty, a chance to consider and be moved by a richer sort of connectedness than our lives typically allow. Goldsworthy steeps himself in forests and streams, creating sculpture from driftwood or stones, works that honor the flow of the elements around them — and will eventually be overwhelmed by them.

Goldsworthy has created some permanent works, which we see in the film, but even these are built with humility. Late in the documentary, he apologizes to the crew because he just can’t bring himself to perform the work he had planned for the morning — drill into bedrock. He does subtly alter some landscapes: Inspired by the remains of stone walls built long ago by the first farmers in New England, Goldsworthy splits native boulders in two and then carves a path between them. Much of the work is purely ephemeral, with the film and Goldsworthy’s photographs our only record of it: He and his daughter/assistant wrap his finger and hands in ruby-red flower petals, creating an alien skin. He then dips each hand into a stream, the current tugging the petals away. They parade along with the flow.

One permanent work involves a canvas and could even be hung in a gallery. But here Goldsworthy’s collaborator is sheep: He and his daughter lay a white canvas out in a muddy pasture and then set a bucket of feed in the center. Soon, the flock comes to eat. The completed work, all brown hoofprints, charts the patterns of their milling, making a study of the instinctual choices of livestock. At the center of this muddy study: a circle of white where the bucket had stood.

The title comes from Goldsworthy’s own efforts to get himself fully into the flow of systems indifferent to us. In England, during a windstorm, he stands upon a grassy bluff and faces the gusts, outstretching his hands, leaning his body forward. He stumbles back and forth, sometimes in danger of tumbling over the precipice. The winds batter him backward. But sometimes, for a heartbeat, he’s held there, standing at an almost 45 degree angle, buffeted and supported at one. It’s a dance.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com