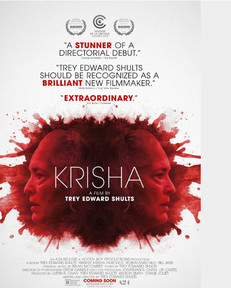

Reviewed by Manohla Dargis – New York Times

Few movies bore into a character’s head as deeply as “Krisha,” and with such uncompromising ferocity. A family drama in alternately appalling and queasily hilarious extremis, this bravura first feature takes place over an epically terrible Thanksgiving that may inspire you to start leafing through the collected poems of Philip Larkin, looking for that one about Mum and Dad. It takes some time to grasp who wronged whom here, but it’s clear from the get go that serious damage has been done.

The young director Trey Edward Shults suggests as much by opening with a close-up of Krisha (played by the director’s aunt Krisha Fairchild) staring into the camera, her lined, tanned face framed by a mass of springy gray hair that might as well be a mess of snakes. She’s isolated in the shot, and, as she continues to stare and the eerie music gets to shrieking, you might think — it won’t be for the first time — that this looks and feels a lot like a horror movie. Though it’s one, after a fashion and too many drinks, that finally owes more to the likes of John Cassavetes than the usual genre influences.

Most of the movie takes place in a sprawling McMansion in Austin, Tex., a multitiered theater that’s already populated with yelling, yammering relations and barking, agitated dogs when Krisha (CREE-sha) rings the doorbell. She arrives in a pickup and, notably, first approaches the wrong house. Mr. Shults, who also wrote the streamlined script, lets the story emerge through such seemingly minor incidents, as well as through conversational snippets, private rituals and the sort of choreography of chaos that — as bodies and cameras pirouette — suggests he has put in time with some touchstones of Eastern European art cinema (Emir Kusturica, Alexei German).

Even as Mr. Shults goes light on the exposition, the characters — with their rapid gestures, cacophonous movements and ductile faces — express a great deal. The extraordinary peripatetic camerawork and fluid editing (the cinematographer is Drew Daniels; Mr. Shults is the editor) bring characters together, even when they’re not talking to one another, the rapid lateral pans mapping relationships with revelatory geometric precision. And while Mr. Shults does leave Krisha to check in on the other relatives (wrestling, shouting, nuzzling, conspiring), the camera is largely associated with her, beginning with the long take that starts at her truck and ends in the house.

At once a stage and a confessional, the house becomes the site of Krisha’s undoing, a process she hurries along with furtively swallowed pills she keeps in a small locked box marked “private.” This little safe, with its childish scrawl and adult contents (a Pandora’s boxful of woe), is a perfect manifestation of Krisha, who is herself in mysterious lockdown. (She keeps the key to her safe on a chain around her neck.) Much of the movie, which runs a very fast, expertly jammed 82 minutes, involves opening Krisha, as it were. It’s a revelation (at times more like an exhumation) that involves old and new wounds and reaches a frenzied climax with a culinary catastrophe.

Mr. Shults maintains tight control over his whirring parts almost to the frenetic finish, so it’s all the more impressive that he cast not just his aunt, but also himself, his mother and grandmother in several critical roles. This gives the movie an extra frisson, adding to its portrait of a self-destructive woman. There can be something pitiless about Mr. Shults’s gaze, but the steadiness of his look is that of the artist who refuses to sell the truth out for sentimentalism. When Krisha stands in the kitchen, wild-eyed amid all these human sights and sounds, you see a woman overwhelmed by life itself, as well as a movie that is an expressionistic tour de force.

A DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

Few movies bore into a character’s head as deeply as “Krisha,” and with such uncompromising ferocity. A family drama in alternately appalling and queasily hilarious extremis, this bravura first feature takes place over an epically terrible Thanksgiving that may inspire you to start leafing through the collected poems of Philip Larkin, looking for that one about Mum and Dad. It takes some time to grasp who wronged whom here, but it’s clear from the get go that serious damage has been done.

The young director Trey Edward Shults suggests as much by opening with a close-up of Krisha (played by the director’s aunt Krisha Fairchild) staring into the camera, her lined, tanned face framed by a mass of springy gray hair that might as well be a mess of snakes. She’s isolated in the shot, and, as she continues to stare and the eerie music gets to shrieking, you might think — it won’t be for the first time — that this looks and feels a lot like a horror movie. Though it’s one, after a fashion and too many drinks, that finally owes more to the likes of John Cassavetes than the usual genre influences.

Most of the movie takes place in a sprawling McMansion in Austin, Tex., a multitiered theater that’s already populated with yelling, yammering relations and barking, agitated dogs when Krisha (CREE-sha) rings the doorbell. She arrives in a pickup and, notably, first approaches the wrong house. Mr. Shults, who also wrote the streamlined script, lets the story emerge through such seemingly minor incidents, as well as through conversational snippets, private rituals and the sort of choreography of chaos that — as bodies and cameras pirouette — suggests he has put in time with some touchstones of Eastern European art cinema (Emir Kusturica, Alexei German).

Even as Mr. Shults goes light on the exposition, the characters — with their rapid gestures, cacophonous movements and ductile faces — express a great deal. The extraordinary peripatetic camerawork and fluid editing (the cinematographer is Drew Daniels; Mr. Shults is the editor) bring characters together, even when they’re not talking to one another, the rapid lateral pans mapping relationships with revelatory geometric precision. And while Mr. Shults does leave Krisha to check in on the other relatives (wrestling, shouting, nuzzling, conspiring), the camera is largely associated with her, beginning with the long take that starts at her truck and ends in the house.

At once a stage and a confessional, the house becomes the site of Krisha’s undoing, a process she hurries along with furtively swallowed pills she keeps in a small locked box marked “private.” This little safe, with its childish scrawl and adult contents (a Pandora’s boxful of woe), is a perfect manifestation of Krisha, who is herself in mysterious lockdown. (She keeps the key to her safe on a chain around her neck.) Much of the movie, which runs a very fast, expertly jammed 82 minutes, involves opening Krisha, as it were. It’s a revelation (at times more like an exhumation) that involves old and new wounds and reaches a frenzied climax with a culinary catastrophe.

Mr. Shults maintains tight control over his whirring parts almost to the frenetic finish, so it’s all the more impressive that he cast not just his aunt, but also himself, his mother and grandmother in several critical roles. This gives the movie an extra frisson, adding to its portrait of a self-destructive woman. There can be something pitiless about Mr. Shults’s gaze, but the steadiness of his look is that of the artist who refuses to sell the truth out for sentimentalism. When Krisha stands in the kitchen, wild-eyed amid all these human sights and sounds, you see a woman overwhelmed by life itself, as well as a movie that is an expressionistic tour de force.

A DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members