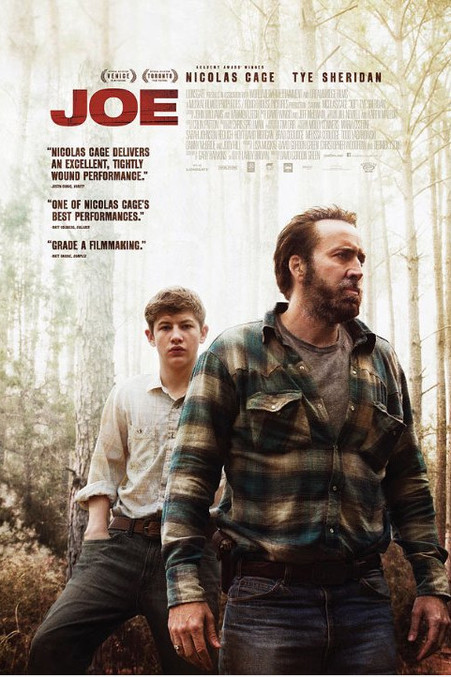

CAST & CREDITS

Featuring Nicolas Cage

Tye Sheridan

Gary Poulter

Directed by David Gordon Green

2014 Running time: 117 minutes.

Featuring Nicolas Cage

Tye Sheridan

Gary Poulter

Directed by David Gordon Green

2014 Running time: 117 minutes.

Reviewed by Stephen Holden – NYT

The most indelible scenes in David Gordon Green’s “Joe,” filmed in the backwoods of Texas, have the fierce clarity of illuminations glimpsed in a lightning flash. In one lingering afterimage, a team of mostly African-American laborers, toiling in a desiccated pine forest, methodically poison sickly trees with “juice hatchets” (small axes that squirt deadly herbicide) to kill them off and make room for the planting of hardier species. These woodsmen, played by nonprofessionals, share an easy, rough-hewn camaraderie. They are the least tormented characters in “Joe,” a punishing exercise in Southern miserablism.

Watching these early scenes in the movie, whose screenplay was adapted by Gary Hawkins from a 1990 novel by Larry Brown, I had the sensation of being thrust into a primitive, half-forgotten world, somewhere out of time. Brought to scorching life by Mr. Green’s longtime cinematographer Tim Orr, it registers as simultaneously ordinary and mythic, the wild, scruffy landscape evoking the tragic weight of American history. These ignorant, desperate rural poor people are so cut off from modern civilization, they seem hardly aware of the outside world.

At the heart of the movie stands its conflicted title character, Joe (Nicolas Cage), the good-bad supervisor of the tree poisoners. A hothead who has served time in a penitentiary, Joe is watched wherever he goes by the police, who try to goad him into lashing out. Also hounding Joe is Willie (Ronnie Gene Blevins), a snarling scar-faced sociopath who has been stalking him with a gun since they tangled in a bar.

In a scene that illustrates the movie’s bestial view of humanity, Joe brings his beloved brown-and-white bulldog to a brothel, where he leaves the animal to fight with another unleashed dog while he enjoys a quickie with a prostitute.

Dogs are everywhere, barking, snarling, snapping and straining at their leashes whenever a stranger approaches a house. In one of the more disturbing, if unsubtle, comparisons the movie makes, “Joe” wonders: Which are more feral, the dogs or their human keepers? Throughout the film, the dog-eat-dog metaphor is worked nearly to death.

This is a society in which women shrink into the background, and the men seem to subsist on cigarettes and cheap liquor, which they swill from the bottle and use to fuel a rage that makes them feel alive. It’s all they can do not to kill one another.

The local color is so pungent that it overwhelms the too-sentimental story of Joe’s redemptive mentoring of an ingenuous, hardy 15-year-old boy, Gary (Tye Sheridan, seen in “The Tree of Life” and “Mud”), who approaches Joe in the pine lands looking for work. As the days pass, Joe warms to Gary and becomes a surrogate father to someone who needs all the paternal encouragement he can get.

Gary’s real father, Wade (Gary Poulter, a nonprofessional actor who died after “Joe” was completed), is a violent drunk and scraggly parasite with a cowering wife and an abused daughter too traumatized to speak. Once Gary starts working for Joe, Wade begins stealing his cash and beating him up. Wade is a wild creature not unlike the poisonous snake Joe catches early in the movie.

From the start, “Joe” reads as a quasi-biblical parable in which Joe’s good and bad instincts are at war. It leads to a grisly but ultimately anticlimactic showdown in which Joe goes after Willie and Wade, who have joined forces in a kidnapping scheme.

Mr. Cage gives his most committed performance in years as this divided soul, but it still looks like acting when compared with Mr. Poulter’s embodiment of pure evil. No glib psychological explanation is offered to explain Wade, a predator whose hatred of the world leaks out of his eyes like a toxin that can’t be contained in his wiry body. Like snakes, some men are born venomous.

The most indelible scenes in David Gordon Green’s “Joe,” filmed in the backwoods of Texas, have the fierce clarity of illuminations glimpsed in a lightning flash. In one lingering afterimage, a team of mostly African-American laborers, toiling in a desiccated pine forest, methodically poison sickly trees with “juice hatchets” (small axes that squirt deadly herbicide) to kill them off and make room for the planting of hardier species. These woodsmen, played by nonprofessionals, share an easy, rough-hewn camaraderie. They are the least tormented characters in “Joe,” a punishing exercise in Southern miserablism.

Watching these early scenes in the movie, whose screenplay was adapted by Gary Hawkins from a 1990 novel by Larry Brown, I had the sensation of being thrust into a primitive, half-forgotten world, somewhere out of time. Brought to scorching life by Mr. Green’s longtime cinematographer Tim Orr, it registers as simultaneously ordinary and mythic, the wild, scruffy landscape evoking the tragic weight of American history. These ignorant, desperate rural poor people are so cut off from modern civilization, they seem hardly aware of the outside world.

At the heart of the movie stands its conflicted title character, Joe (Nicolas Cage), the good-bad supervisor of the tree poisoners. A hothead who has served time in a penitentiary, Joe is watched wherever he goes by the police, who try to goad him into lashing out. Also hounding Joe is Willie (Ronnie Gene Blevins), a snarling scar-faced sociopath who has been stalking him with a gun since they tangled in a bar.

In a scene that illustrates the movie’s bestial view of humanity, Joe brings his beloved brown-and-white bulldog to a brothel, where he leaves the animal to fight with another unleashed dog while he enjoys a quickie with a prostitute.

Dogs are everywhere, barking, snarling, snapping and straining at their leashes whenever a stranger approaches a house. In one of the more disturbing, if unsubtle, comparisons the movie makes, “Joe” wonders: Which are more feral, the dogs or their human keepers? Throughout the film, the dog-eat-dog metaphor is worked nearly to death.

This is a society in which women shrink into the background, and the men seem to subsist on cigarettes and cheap liquor, which they swill from the bottle and use to fuel a rage that makes them feel alive. It’s all they can do not to kill one another.

The local color is so pungent that it overwhelms the too-sentimental story of Joe’s redemptive mentoring of an ingenuous, hardy 15-year-old boy, Gary (Tye Sheridan, seen in “The Tree of Life” and “Mud”), who approaches Joe in the pine lands looking for work. As the days pass, Joe warms to Gary and becomes a surrogate father to someone who needs all the paternal encouragement he can get.

Gary’s real father, Wade (Gary Poulter, a nonprofessional actor who died after “Joe” was completed), is a violent drunk and scraggly parasite with a cowering wife and an abused daughter too traumatized to speak. Once Gary starts working for Joe, Wade begins stealing his cash and beating him up. Wade is a wild creature not unlike the poisonous snake Joe catches early in the movie.

From the start, “Joe” reads as a quasi-biblical parable in which Joe’s good and bad instincts are at war. It leads to a grisly but ultimately anticlimactic showdown in which Joe goes after Willie and Wade, who have joined forces in a kidnapping scheme.

Mr. Cage gives his most committed performance in years as this divided soul, but it still looks like acting when compared with Mr. Poulter’s embodiment of pure evil. No glib psychological explanation is offered to explain Wade, a predator whose hatred of the world leaks out of his eyes like a toxin that can’t be contained in his wiry body. Like snakes, some men are born venomous.