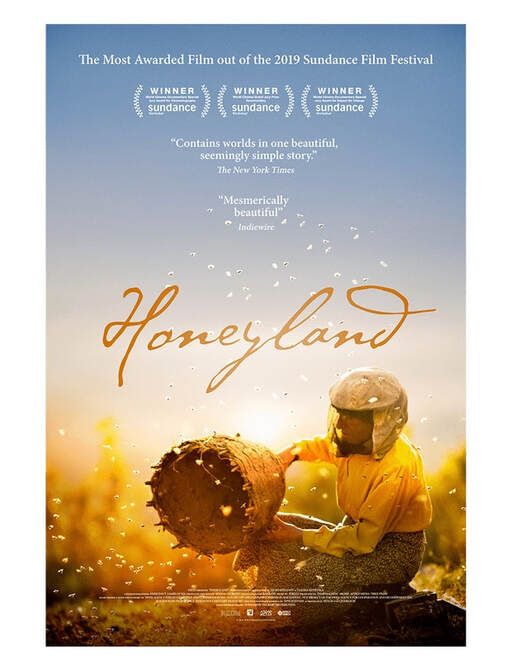

HONEYLAND

Monday, February 17, 7:30 pm

CAST & CREW

Directed by Ljubomir Stefanov and Tamara Kotevska

Featuring Hatidze Muratova,

Hussein Sam & Ljutvie Sam

Not Rated 90 mins.

Directed by Ljubomir Stefanov and Tamara Kotevska

Featuring Hatidze Muratova,

Hussein Sam & Ljutvie Sam

Not Rated 90 mins.

Reviewed by Ty Burr | Boston Globe

A documentary about a Macedonian beekeeper doesn’t sound like one of the best films of the year, does it? But few movies capture the great wheel of nature turning with as much beauty and empathy as “Honeyland,” and fewer still show how easily the wheel can slip its track and come crashing to pieces. Directed by Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov, it won three awards at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, including cinematography and grand jury prizes, and everyone who sees it seems to come away with their senses scrubbed clean.

“Honeyland” introduces us to Hatidze Muratova, a great character and a natural-born movie star. She lives in the ruins of a farming village several hours from the capital city of Skopje, a 50-something woman with terrible teeth and an unquenchable spirit. In the film’s opening sequence, Muratova climbs up into the mountains surrounding her home — the camerawork by Fejmi Daut and Samir Ljuma revels in the vastness of the land — and pulls away a piece of rocky ledge to reveal a honeybee colony fizzing away beneath. It’s a breathtaking reveal; proof of magic yanked straight from the earth.

Muratova tends to several of these natural colonies as well as a number of homemade hives; she harvests the honey and takes the long bus ride into Skopje to sell it at open-air markets, sweet-talking the stall owners and netting 10 euros a jar. When taking the honeycombs, she always makes sure to leave half in the hives, to keep the colony flourishing. Back at Hatidze’s hut, her only companions are a rangy dog and her 84-year-old mother, Nazife, bedridden and nearly blind. They all seem to have been there for centuries. Certainly this way of life has.

Kotevska and Stefanov filmed with lightweight, unobtrusive equipment over three years, and they record the slow eruption of a conflict. One day a family arrives in the valley: father Hussein Sam, his wife, Ljutvie, seven fractious kids, a herd of cattle, and several vehicles and trailers in various states of disrepair. A long shot of Muratova peering over a wall at the interlopers tells you everything you need to know about her wariness, but she befriends the children and then, slowly, the parents. And then Hussein decides to get in on the honeybee business himself.

What happens next in “Honeyland” feels like a push-pull as old as time — between man and nature, men and women, living off the land versus living with it — yet it’s absolutely relevant to where we find ourselves now, in a time of worldwide honeybee colony collapse disorder. That’s the film’s genius: It’s both allegory and example, a symbolic tale about the importance of nature’s balance and a specific story about these specific lives.

As such, the movie’s funny and wrenching, depressing and full of wonders. There’s no narration (although Hatidze talks easily to the camera, her mother, her dog, herself), and the film’s details tumble out the way life does. We feel for the father — he has eight mouths to feed and cattle farming doesn’t seem his forte — but we also note where need turns to overuse turns to plunder. “Honeyland” resists villainizing; even the city merchant pressuring Hussein to provide more honey has his reasons. The larger problem is too big for these people to understand (although we do). The solution is right there at hand, for anyone with the patience and willingness to see.

One of the boys sees. The second to oldest, he takes an interest in Muratova’s methods, and she starts to take him along on her trips to the highlands, teaching him the hidden arts of beekeeping. This is how it happens, you realize — the handing on of lore, the fanning of the flame — even as the modern world treats that wisdom the same way Hussein treats his son, with a condescending cuff to the back of the head.

Grave and wise, “Honeyland” is ultimately an act of faith, and the filmmakers extend the idea of balance all the way to the film’s implicit moral. And Hatidze herself is a figure for the ages, drawing the honey from life while working to ensure it’s there for the generations to come. The hive she tends is bigger than she knows.

In Turkish, Bosnian and Macedonian with English subtitles.

A documentary about a Macedonian beekeeper doesn’t sound like one of the best films of the year, does it? But few movies capture the great wheel of nature turning with as much beauty and empathy as “Honeyland,” and fewer still show how easily the wheel can slip its track and come crashing to pieces. Directed by Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov, it won three awards at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, including cinematography and grand jury prizes, and everyone who sees it seems to come away with their senses scrubbed clean.

“Honeyland” introduces us to Hatidze Muratova, a great character and a natural-born movie star. She lives in the ruins of a farming village several hours from the capital city of Skopje, a 50-something woman with terrible teeth and an unquenchable spirit. In the film’s opening sequence, Muratova climbs up into the mountains surrounding her home — the camerawork by Fejmi Daut and Samir Ljuma revels in the vastness of the land — and pulls away a piece of rocky ledge to reveal a honeybee colony fizzing away beneath. It’s a breathtaking reveal; proof of magic yanked straight from the earth.

Muratova tends to several of these natural colonies as well as a number of homemade hives; she harvests the honey and takes the long bus ride into Skopje to sell it at open-air markets, sweet-talking the stall owners and netting 10 euros a jar. When taking the honeycombs, she always makes sure to leave half in the hives, to keep the colony flourishing. Back at Hatidze’s hut, her only companions are a rangy dog and her 84-year-old mother, Nazife, bedridden and nearly blind. They all seem to have been there for centuries. Certainly this way of life has.

Kotevska and Stefanov filmed with lightweight, unobtrusive equipment over three years, and they record the slow eruption of a conflict. One day a family arrives in the valley: father Hussein Sam, his wife, Ljutvie, seven fractious kids, a herd of cattle, and several vehicles and trailers in various states of disrepair. A long shot of Muratova peering over a wall at the interlopers tells you everything you need to know about her wariness, but she befriends the children and then, slowly, the parents. And then Hussein decides to get in on the honeybee business himself.

What happens next in “Honeyland” feels like a push-pull as old as time — between man and nature, men and women, living off the land versus living with it — yet it’s absolutely relevant to where we find ourselves now, in a time of worldwide honeybee colony collapse disorder. That’s the film’s genius: It’s both allegory and example, a symbolic tale about the importance of nature’s balance and a specific story about these specific lives.

As such, the movie’s funny and wrenching, depressing and full of wonders. There’s no narration (although Hatidze talks easily to the camera, her mother, her dog, herself), and the film’s details tumble out the way life does. We feel for the father — he has eight mouths to feed and cattle farming doesn’t seem his forte — but we also note where need turns to overuse turns to plunder. “Honeyland” resists villainizing; even the city merchant pressuring Hussein to provide more honey has his reasons. The larger problem is too big for these people to understand (although we do). The solution is right there at hand, for anyone with the patience and willingness to see.

One of the boys sees. The second to oldest, he takes an interest in Muratova’s methods, and she starts to take him along on her trips to the highlands, teaching him the hidden arts of beekeeping. This is how it happens, you realize — the handing on of lore, the fanning of the flame — even as the modern world treats that wisdom the same way Hussein treats his son, with a condescending cuff to the back of the head.

Grave and wise, “Honeyland” is ultimately an act of faith, and the filmmakers extend the idea of balance all the way to the film’s implicit moral. And Hatidze herself is a figure for the ages, drawing the honey from life while working to ensure it’s there for the generations to come. The hive she tends is bigger than she knows.

In Turkish, Bosnian and Macedonian with English subtitles.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.