“We are in the hands of one of cinema’s modern masters.” --Pete Hammond, Deadline

“Sorrentino’s most personal movie is also his best” --IndieWire

“A joy to witness.” --Time Out

“A sublime masterpiece.” --AwardsWatch

“Sorrentino’s most personal movie is also his best” --IndieWire

“A joy to witness.” --Time Out

“A sublime masterpiece.” --AwardsWatch

The Oscar-winning Italian director pens a love letter to his native Naples, looking back poignantly at the formative experiences of his youth in the 1980s.

Reviewed by David Rooney | Hollywood Reporter

If The Great Beauty was Paolo Sorrentino’s extravagant homage to La Dolce Vita — with nods also to 8½ and Roma — The Hand of God is the Italian Oscar winner’s Amarcord. But although the Fellini inspiration is acknowledged in the story in an amusing audition scene, this is an intensely personal film, very much imprinted with Sorrentino’s own signature. Returning to his Neapolitan roots to reflect on the experiences of the tender teenage years that shaped him has brought out sumptuous veins of joy and sorrow that feel richer, deeper, more searingly poignant than anything the director has done before.

This exquisitely crafted homecoming doubles as a hymn to the glories of Naples — the beauty of its gulf coast, the decaying splendor of its architecture, the lusty musicality of its vernacular and the vitality and natural humor of its people. It’s the work of a director in full command of his gifts, from the kaleidoscopic vignettes of family life that make the first half such a constant delight through the supple modulation of tone midway, when shocking tragedy prompts a shift into a more ruminative mood.

The whimsical opening captures the overlapping influences of religion and superstition so prevalent in Neapolitan culture. Daria D’Antonio’s camera speeds across the Bay of Naples, its waters glimmering in the evening sun, as a vintage auto putts along the road that hugs the coast before pulling up at a city bus stop.

Standing out among a line of weary-looking commuters is Patrizia (Luisa Ranieri), a strikingly sensual woman poured into a revealing white summer dress. The chauffeured car’s passenger identifies himself as San Gennaro (Enzo Decaro), patron saint of Naples. Patrizia is disconcerted that the stranger knows her name, that of her husband and their problems conceiving a child. But when he offers her a lift home and a solution to her childlessness, she climbs aboard.

The scene that follows — involving the Neapolitan folkloric figure of a child monk in a crumbling yet magnificent palazzo with a fallen chandelier that still glows — gets even more eccentric. But when Patrizia returns home that night convinced she’s experienced a miracle, her jealous husband, Franco (Massimiliano Gallo), accuses her of staying out whoring. Seemingly not for the first time, she calls her big sister, Maria (Teresa Saponangelo), for help when Franco threatens violence.

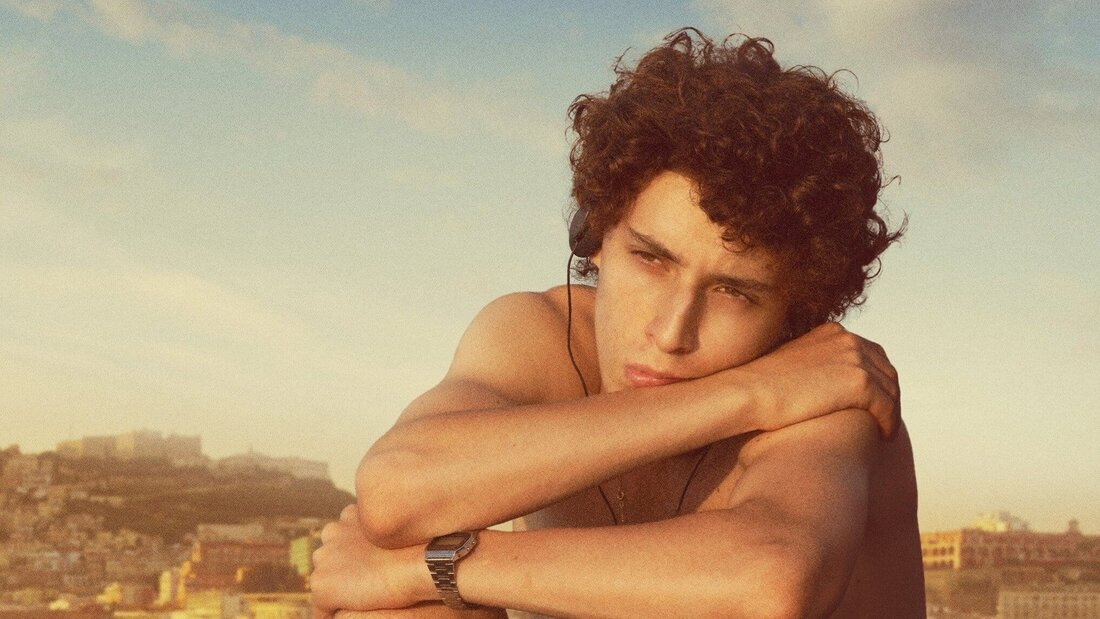

Maria speeds across town to defuse the situation with a few calming words, squished on a moped between her husband, Saverio (Toni Servillo), clinging precariously behind her, and their son, Fabietto (Filippo Scotti), at the wheel. That precious moment will return to the teenager — Sorrentino’s fictionalized stand-in — later in the film, a happy memory of the three of them laughing with the wind in their hair.

The entire opening almost could have been plucked from a classic commedia all’italiana, with its collision of the absurd and the domestic. Sorrentino’s fond recollections of the miracles of family life and of his own coming of age — magical and mundane, holy and profane — give the film its furiously beating heart.

The title comes from a controversial goal scored by Diego Maradona in the 1986 World Cup quarterfinal. The will-he-or-won’t-he question of the Argentine soccer superstar being signed to play for Naples runs through the early scenes with a note of low-key suspense, eventually bringing a shot of galvanizing pride to the city. And it’s Maradona, the divinity of the soccer field, who inadvertently saves Fabietto from a terrible fate later in the film.

Anyone who’s ever been in Italy during a big game will recognize the deserted streets and the explosion of noisy celebration from every window and balcony whenever the local team scores. That collective elation, Fabietto comes to realize, is no less present in the ephemeral pleasures of a quick zip across town to help his emotionally unstable aunt or an extended family lunch.

About that lunch: The raucous family meal has a long and treasured history in Italian comedies, and this al fresco get-together at the seaside home of a cheerfully corrupt health inspector and his hilariously sour, foul-mouthed old mother is especially memorable. Sorrentino’s attention to character detail enlivens every moment with warmth and humor, as the entire party then migrates to the shore for a swim off the host’s new boat. Patrizia strips naked to catch some rays, leaving them all dumbstruck and Franco quietly enraged. She fuels the erotic fantasies of Fabietto and his older brother Marchino (Marlon Joubert), an aspiring actor too conventionally handsome to be of interest to the great Fellini.

There’s a lovely, limber quality to the way Sorrentino strings these scenes together, more like an immersive mosaic than a traditional narrative, with none of the ironic distance that has often characterized his work, and few of the stylistic flourishes. “Cinema is a distraction, reality is second-rate,” Fellini is overheard saying at an audition that attracts all manner of fabulous freaks. But the reality of home and family is a grounding force, a source of comfort and security that outlasts all the escapes that life and the pursuit of a career can provide. Sorrentino conjures the lasting memories of his youth for the screen as a loving act of reclamation.

The devastating loss that Fabietto suffers at 17 shatters but also strangely fortifies him as he stumbles forward. He sheds his virginity thanks to an unexpected gesture from a much older neighbor (the priceless Betti Pedrazzi), who explains that she’s simply giving him a hand to see the future. And he is drawn instantly to the wonders of moviemaking when he observes a shoot in the historic Galleria Umberto I. The volatile director of that film, Antonio Capuano (Ciro Capano), becomes an unlikely mentor, encouraging Fabietto to overcome his fears and find his creative voice. (Sorrentino co-wrote Capuano’s 1998 feature The Dust of Naples, when his own career was in its infancy.)

During a sorrowful trip to the volcanic island of Stromboli, a location with its own cinematic history, Marchino admits to his brother that he lacks the perseverance to be an actor. Their sister has even less direction, virtually never leaving the bathroom, in a running gag with a sweet payoff. And Armando (Biagio Manna), a small-time crook who befriends Fabietto, reveals the fragility of all his big talk about living large. As Fabietto evolves into the more mature Fabio, however, he finds the strength of character to trust in his instincts and seize his liberation.

There’s no self-aggrandizement in Sorrentino’s introspection, and no sticky sentimentality in his nostalgia. Instead, there’s an intimate candor that sneaks up on you as the film’s fragmented storytelling comes together into something quite special, a coming-of-age story marked by indelible tragedy, an unspeakable pain that becomes a companion. The emotional resonance is amplified by the elegant compositions of D’Antonio’s cinematography and the melancholy pull of Lele Marchitelli’s score.

While Servillo has long been the expressively world-weary face of Sorrentino’s films, his Saverio, a flawed yet steadfast father, blends here into a large ensemble full of zesty characterizations, with memorable work in particular from Saponangelo and Ranieri as the polar-opposite sisters. But the indispensable glue is provided by relative newcomer Scotti’s Fabietto, whose carefree behavior in the early scenes doesn’t mask his sensitivity. Watching him learn to see his world and the people in it with new eyes after absorbing a crushing blow is profoundly affecting.

Reviewed by David Rooney | Hollywood Reporter

If The Great Beauty was Paolo Sorrentino’s extravagant homage to La Dolce Vita — with nods also to 8½ and Roma — The Hand of God is the Italian Oscar winner’s Amarcord. But although the Fellini inspiration is acknowledged in the story in an amusing audition scene, this is an intensely personal film, very much imprinted with Sorrentino’s own signature. Returning to his Neapolitan roots to reflect on the experiences of the tender teenage years that shaped him has brought out sumptuous veins of joy and sorrow that feel richer, deeper, more searingly poignant than anything the director has done before.

This exquisitely crafted homecoming doubles as a hymn to the glories of Naples — the beauty of its gulf coast, the decaying splendor of its architecture, the lusty musicality of its vernacular and the vitality and natural humor of its people. It’s the work of a director in full command of his gifts, from the kaleidoscopic vignettes of family life that make the first half such a constant delight through the supple modulation of tone midway, when shocking tragedy prompts a shift into a more ruminative mood.

The whimsical opening captures the overlapping influences of religion and superstition so prevalent in Neapolitan culture. Daria D’Antonio’s camera speeds across the Bay of Naples, its waters glimmering in the evening sun, as a vintage auto putts along the road that hugs the coast before pulling up at a city bus stop.

Standing out among a line of weary-looking commuters is Patrizia (Luisa Ranieri), a strikingly sensual woman poured into a revealing white summer dress. The chauffeured car’s passenger identifies himself as San Gennaro (Enzo Decaro), patron saint of Naples. Patrizia is disconcerted that the stranger knows her name, that of her husband and their problems conceiving a child. But when he offers her a lift home and a solution to her childlessness, she climbs aboard.

The scene that follows — involving the Neapolitan folkloric figure of a child monk in a crumbling yet magnificent palazzo with a fallen chandelier that still glows — gets even more eccentric. But when Patrizia returns home that night convinced she’s experienced a miracle, her jealous husband, Franco (Massimiliano Gallo), accuses her of staying out whoring. Seemingly not for the first time, she calls her big sister, Maria (Teresa Saponangelo), for help when Franco threatens violence.

Maria speeds across town to defuse the situation with a few calming words, squished on a moped between her husband, Saverio (Toni Servillo), clinging precariously behind her, and their son, Fabietto (Filippo Scotti), at the wheel. That precious moment will return to the teenager — Sorrentino’s fictionalized stand-in — later in the film, a happy memory of the three of them laughing with the wind in their hair.

The entire opening almost could have been plucked from a classic commedia all’italiana, with its collision of the absurd and the domestic. Sorrentino’s fond recollections of the miracles of family life and of his own coming of age — magical and mundane, holy and profane — give the film its furiously beating heart.

The title comes from a controversial goal scored by Diego Maradona in the 1986 World Cup quarterfinal. The will-he-or-won’t-he question of the Argentine soccer superstar being signed to play for Naples runs through the early scenes with a note of low-key suspense, eventually bringing a shot of galvanizing pride to the city. And it’s Maradona, the divinity of the soccer field, who inadvertently saves Fabietto from a terrible fate later in the film.

Anyone who’s ever been in Italy during a big game will recognize the deserted streets and the explosion of noisy celebration from every window and balcony whenever the local team scores. That collective elation, Fabietto comes to realize, is no less present in the ephemeral pleasures of a quick zip across town to help his emotionally unstable aunt or an extended family lunch.

About that lunch: The raucous family meal has a long and treasured history in Italian comedies, and this al fresco get-together at the seaside home of a cheerfully corrupt health inspector and his hilariously sour, foul-mouthed old mother is especially memorable. Sorrentino’s attention to character detail enlivens every moment with warmth and humor, as the entire party then migrates to the shore for a swim off the host’s new boat. Patrizia strips naked to catch some rays, leaving them all dumbstruck and Franco quietly enraged. She fuels the erotic fantasies of Fabietto and his older brother Marchino (Marlon Joubert), an aspiring actor too conventionally handsome to be of interest to the great Fellini.

There’s a lovely, limber quality to the way Sorrentino strings these scenes together, more like an immersive mosaic than a traditional narrative, with none of the ironic distance that has often characterized his work, and few of the stylistic flourishes. “Cinema is a distraction, reality is second-rate,” Fellini is overheard saying at an audition that attracts all manner of fabulous freaks. But the reality of home and family is a grounding force, a source of comfort and security that outlasts all the escapes that life and the pursuit of a career can provide. Sorrentino conjures the lasting memories of his youth for the screen as a loving act of reclamation.

The devastating loss that Fabietto suffers at 17 shatters but also strangely fortifies him as he stumbles forward. He sheds his virginity thanks to an unexpected gesture from a much older neighbor (the priceless Betti Pedrazzi), who explains that she’s simply giving him a hand to see the future. And he is drawn instantly to the wonders of moviemaking when he observes a shoot in the historic Galleria Umberto I. The volatile director of that film, Antonio Capuano (Ciro Capano), becomes an unlikely mentor, encouraging Fabietto to overcome his fears and find his creative voice. (Sorrentino co-wrote Capuano’s 1998 feature The Dust of Naples, when his own career was in its infancy.)

During a sorrowful trip to the volcanic island of Stromboli, a location with its own cinematic history, Marchino admits to his brother that he lacks the perseverance to be an actor. Their sister has even less direction, virtually never leaving the bathroom, in a running gag with a sweet payoff. And Armando (Biagio Manna), a small-time crook who befriends Fabietto, reveals the fragility of all his big talk about living large. As Fabietto evolves into the more mature Fabio, however, he finds the strength of character to trust in his instincts and seize his liberation.

There’s no self-aggrandizement in Sorrentino’s introspection, and no sticky sentimentality in his nostalgia. Instead, there’s an intimate candor that sneaks up on you as the film’s fragmented storytelling comes together into something quite special, a coming-of-age story marked by indelible tragedy, an unspeakable pain that becomes a companion. The emotional resonance is amplified by the elegant compositions of D’Antonio’s cinematography and the melancholy pull of Lele Marchitelli’s score.

While Servillo has long been the expressively world-weary face of Sorrentino’s films, his Saverio, a flawed yet steadfast father, blends here into a large ensemble full of zesty characterizations, with memorable work in particular from Saponangelo and Ranieri as the polar-opposite sisters. But the indispensable glue is provided by relative newcomer Scotti’s Fabietto, whose carefree behavior in the early scenes doesn’t mask his sensitivity. Watching him learn to see his world and the people in it with new eyes after absorbing a crushing blow is profoundly affecting.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$7.00 Members | $11.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue | Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 | classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs

$7.00 Members | $11.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue | Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 | classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs