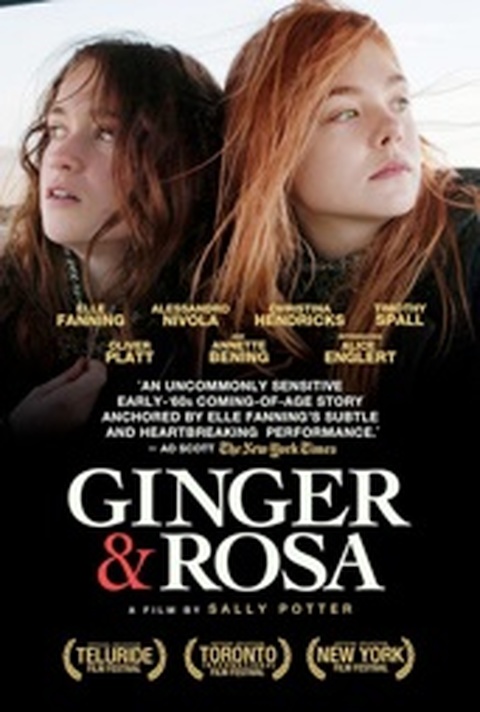

CAST & CREW

Featuring

Elle Fanning

Alice Englert & Christina Hendricks

Directed by Sally Potter

Running time: 90 minutes

Rated R PG-13

Featuring

Elle Fanning

Alice Englert & Christina Hendricks

Directed by Sally Potter

Running time: 90 minutes

Rated R PG-13

Reviewed by Ty Burr

What makes a coming-of-age movie work? Lord knows we get enough of them: overripe period pieces in which a filmmaker re-creates a precise cultural moment and his or her adolescent struggles with parents and injustice and best friends and sex. Usually, it comes down to the metaphysics of personal observation, which means the secondary characters can be well drawn while the protagonist remains an underwritten blank. It’s hard to see yourself when you’re looking through your own eyes.

Playing at: Kendall Square That isn’t a problem in Sally Potter’s “Ginger & Rosa,” but only because Elle Fanning has the lead role of Ginger, a 16-year-old girl in 1962 London. Only 13 when the film was shot, the actress has a luminous naturalism that seems the opposite of performance: Emotions tumble forth from inside her, often in tight close-up, with a tremulousness that’s specific and real and heartbreaking. Where her older sister, Dakota, has the brazen skills of a born trouper, Elle’s acting feels artless and naive, and all the more powerful for it. Fanning easily convinces you of Ginger’s emotional reality — that every moment is the only moment.

It’s a great performance in a good movie, one that represents a daunting filmmaker’s most mainstream work to date. Potter got her start with experimental films and performance art in the ’60s and ’70s, and her 1992 Virginia Woolf adaptation “Orlando” remains her best-known movie. As recently as 2004’s “Yes” she was writing modern-day dramas in iambic pentameter, and, with 2009’s little-seen “Rage,” she premiered a motion picture via cellphone.

“Ginger & Rosa” is comparatively straightforward stuff, Potter’s gracefully fictionalized reminiscences of growing up in the shadow of the Cuban Missile Crisis and imminent nuclear annihilation. Ginger’s mother and father are bohemian intellectuals (as Potter’s parents were; the film’s dedicated to her mother), part of the British generation that came of age, hard, during WWII. Roland (Alessandro Nivola) was a conscientious objector during the war and wears his prison time as a badge of honor; he’s also a Hot Dad, and he knows it. When Ginger’s best friend, Rosa (Alice Englert), starts playing eye-hockey with him in a car’s rear-view mirror, you dread what’s coming and feel powerless to stop it.

Ginger’s mother, Natalie, is an artist who has given up painting for a life of domesticity, and in her Potter acknowledges a generation of strong women neutered by feckless men. (Some of the same concerns turn up in the adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road,” also opening in the area today.) Christina Hendricks — Joan of “Mad Men” — is a striking visual presence but a hesitant dramatic one in the role, hobbled by a hither-and-yon English accent. Timothy Spall, Oliver Platt, and especially Annette Bening register with more force as concerned family friends, the latter two bluff and American.

The focus is, as it should be, on Ginger as she goes to Ban the Bomb marches, ignores the growing attraction between her father and her friend, and struggles to become a poet. (“I thought you already were one,” Rosa drily observes.) “Ginger & Rosa” gets the period details exactly right — girls ironing their hair and wearing blue jeans in the bathtub — and the music choices are unerring, from “Tutti-Frutti” blaring on a jukebox to Thelonious Monk’s “The Man I Love” under the end credits, a helpless admission of a filmmaker’s ongoing love for a flawed father.

Still, it’s Fanning’s movie, and Potter films her from an aching teenage point of view, the camera looming in too close, the emotions too big to say. It’s not a showy performance; rather, the actress holds back and lets her big, watchful eyes well up with betrayals global and familial, until the panic finally crashes to the surface. Englert, a good actress with an interesting pedigree of her own (she’s the daughter of director Jane Campion) recedes into the background. “Ginger & Rosa” is about adolescence as a state of absolute idealism and absolute self-absorption — a time when there’s no difference between the world’s calamities and one’s own. In Fanning, Potter has found the perfect vessel, and the miracle is that the actress doesn’t even seem to be trying. She just is.

What makes a coming-of-age movie work? Lord knows we get enough of them: overripe period pieces in which a filmmaker re-creates a precise cultural moment and his or her adolescent struggles with parents and injustice and best friends and sex. Usually, it comes down to the metaphysics of personal observation, which means the secondary characters can be well drawn while the protagonist remains an underwritten blank. It’s hard to see yourself when you’re looking through your own eyes.

Playing at: Kendall Square That isn’t a problem in Sally Potter’s “Ginger & Rosa,” but only because Elle Fanning has the lead role of Ginger, a 16-year-old girl in 1962 London. Only 13 when the film was shot, the actress has a luminous naturalism that seems the opposite of performance: Emotions tumble forth from inside her, often in tight close-up, with a tremulousness that’s specific and real and heartbreaking. Where her older sister, Dakota, has the brazen skills of a born trouper, Elle’s acting feels artless and naive, and all the more powerful for it. Fanning easily convinces you of Ginger’s emotional reality — that every moment is the only moment.

It’s a great performance in a good movie, one that represents a daunting filmmaker’s most mainstream work to date. Potter got her start with experimental films and performance art in the ’60s and ’70s, and her 1992 Virginia Woolf adaptation “Orlando” remains her best-known movie. As recently as 2004’s “Yes” she was writing modern-day dramas in iambic pentameter, and, with 2009’s little-seen “Rage,” she premiered a motion picture via cellphone.

“Ginger & Rosa” is comparatively straightforward stuff, Potter’s gracefully fictionalized reminiscences of growing up in the shadow of the Cuban Missile Crisis and imminent nuclear annihilation. Ginger’s mother and father are bohemian intellectuals (as Potter’s parents were; the film’s dedicated to her mother), part of the British generation that came of age, hard, during WWII. Roland (Alessandro Nivola) was a conscientious objector during the war and wears his prison time as a badge of honor; he’s also a Hot Dad, and he knows it. When Ginger’s best friend, Rosa (Alice Englert), starts playing eye-hockey with him in a car’s rear-view mirror, you dread what’s coming and feel powerless to stop it.

Ginger’s mother, Natalie, is an artist who has given up painting for a life of domesticity, and in her Potter acknowledges a generation of strong women neutered by feckless men. (Some of the same concerns turn up in the adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road,” also opening in the area today.) Christina Hendricks — Joan of “Mad Men” — is a striking visual presence but a hesitant dramatic one in the role, hobbled by a hither-and-yon English accent. Timothy Spall, Oliver Platt, and especially Annette Bening register with more force as concerned family friends, the latter two bluff and American.

The focus is, as it should be, on Ginger as she goes to Ban the Bomb marches, ignores the growing attraction between her father and her friend, and struggles to become a poet. (“I thought you already were one,” Rosa drily observes.) “Ginger & Rosa” gets the period details exactly right — girls ironing their hair and wearing blue jeans in the bathtub — and the music choices are unerring, from “Tutti-Frutti” blaring on a jukebox to Thelonious Monk’s “The Man I Love” under the end credits, a helpless admission of a filmmaker’s ongoing love for a flawed father.

Still, it’s Fanning’s movie, and Potter films her from an aching teenage point of view, the camera looming in too close, the emotions too big to say. It’s not a showy performance; rather, the actress holds back and lets her big, watchful eyes well up with betrayals global and familial, until the panic finally crashes to the surface. Englert, a good actress with an interesting pedigree of her own (she’s the daughter of director Jane Campion) recedes into the background. “Ginger & Rosa” is about adolescence as a state of absolute idealism and absolute self-absorption — a time when there’s no difference between the world’s calamities and one’s own. In Fanning, Potter has found the perfect vessel, and the miracle is that the actress doesn’t even seem to be trying. She just is.