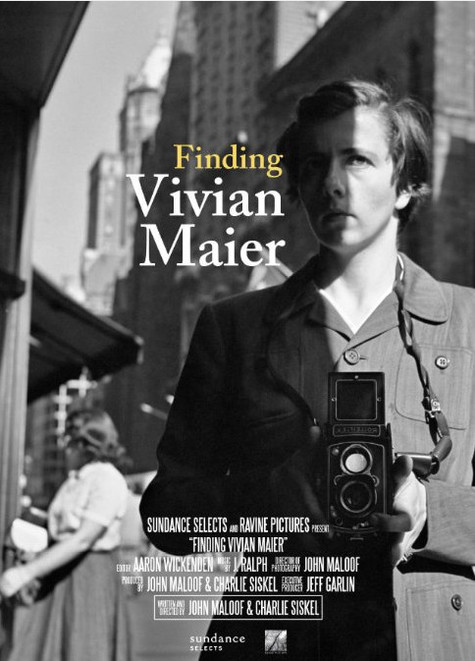

CAST & CREDITS

Featuring: Vivian Maier, John Maloof, Mary Ellen Mark.

Directors: John Maloof, Charlie Siskel

Rating: Not rated Running Time: 83 Mins.

Featuring: Vivian Maier, John Maloof, Mary Ellen Mark.

Directors: John Maloof, Charlie Siskel

Rating: Not rated Running Time: 83 Mins.

Reviewed by Peter Rainer – Christian Science Monitor

Here’s the strange part: In her lifetime, Maier shot more than 100,000 photos and yet didn’t print or even develop most of them. Had Maloof not bought that box, it’s likely her work would have been jettisoned to a junk heap.

“Finding Vivian Maier,” a documentary by Maloof and Charlie Siskel, is a great detective story. How could it be that someone so gifted could limit herself mostly to nannydom all those years? And why did she keep her work hidden away, unexposed even to herself?

As one might imagine, Maloof felt compelled to get answers. Buying up whatever else of Maier’s he was able to locate – and she was a major hoarder, as it turns out – he was able to track down close to a hundred people who knew Maier, including many of the children she cared for, and their parents. One of her employers, for a brief time, was single dad Phil Donahue, who, like the others, is interviewed in the film at length.

In the pre-Internet era, Maier’s trail might have dead-ended. Even so, when Maloof Googled her, nothing came up. But because Maloof is something of a world-class obsessive, he stayed with the story and rooted out as much as anybody will probably ever know about Maier. If the movie, in a sense, is as much about Maloof as it is about Maier, so be it. Their stories, by necessity, are twinned. But behind it all is Maloof’s simple declaration: “I just wanted people to see this marvelous work.”

We don’t have to take his word for its quality. He lavishes us with her photos, and one after the other is a classic, especially the ones shot in the street of children and the homeless and the dispossessed. Maier, not surprisingly, was an outsider herself, even though she worked most of her life in the bourgeois precincts of suburbia. Unmarried and childless, and reputedly fearful of men, she was born in New York but raised in France with her French mother and Austrian father (who ditched the family early on). Maier moved to Manhattan in her mid-20s and worked in a sweatshop before working on and off as a nanny in Chicago beginning in the mid-1950s.

Most of her photos (which have been collected in a book by Maloof and exhibited widely as a result of his efforts) were taken with her little kids in tow, in the stockyards, on the streets, all over the city. She used a Rolleiflex twin-lens reflex camera, which, as the celebrated photographer (and Maier enthusiast) Joel Meyerowitz notes, allows its user to unobtrusively capture its subjects – the perfect instrument for an artist as fiercely secretive as Maier. (She rarely gave out her real name to people, often calling herself “V. Smith.”)

Maier’s relations with her employers and their children elicit contradictory responses. A few of the grown-up kids speak of a dark side and violent outbursts; others so revered her that, in her later years, when she was close to homeless, they paid for her rent and storage. It’s likely that Maier became a nanny in part because she was trying to capture a happy childhood she never experienced for herself. But amateur psychologizing doesn’t really resolve her mystery; in some ways, the more we learn about her, the greater the enigma.

Her story seems especially enigmatic because in the modern age we are so inured to the culture of celebrity that it seems impossible to imagine anyone disdaining it. Maier is a great artist who discounted adulation entirely. Her life was a masquerade; her genius, quite literally, was unexposed.

Here’s the strange part: In her lifetime, Maier shot more than 100,000 photos and yet didn’t print or even develop most of them. Had Maloof not bought that box, it’s likely her work would have been jettisoned to a junk heap.

“Finding Vivian Maier,” a documentary by Maloof and Charlie Siskel, is a great detective story. How could it be that someone so gifted could limit herself mostly to nannydom all those years? And why did she keep her work hidden away, unexposed even to herself?

As one might imagine, Maloof felt compelled to get answers. Buying up whatever else of Maier’s he was able to locate – and she was a major hoarder, as it turns out – he was able to track down close to a hundred people who knew Maier, including many of the children she cared for, and their parents. One of her employers, for a brief time, was single dad Phil Donahue, who, like the others, is interviewed in the film at length.

In the pre-Internet era, Maier’s trail might have dead-ended. Even so, when Maloof Googled her, nothing came up. But because Maloof is something of a world-class obsessive, he stayed with the story and rooted out as much as anybody will probably ever know about Maier. If the movie, in a sense, is as much about Maloof as it is about Maier, so be it. Their stories, by necessity, are twinned. But behind it all is Maloof’s simple declaration: “I just wanted people to see this marvelous work.”

We don’t have to take his word for its quality. He lavishes us with her photos, and one after the other is a classic, especially the ones shot in the street of children and the homeless and the dispossessed. Maier, not surprisingly, was an outsider herself, even though she worked most of her life in the bourgeois precincts of suburbia. Unmarried and childless, and reputedly fearful of men, she was born in New York but raised in France with her French mother and Austrian father (who ditched the family early on). Maier moved to Manhattan in her mid-20s and worked in a sweatshop before working on and off as a nanny in Chicago beginning in the mid-1950s.

Most of her photos (which have been collected in a book by Maloof and exhibited widely as a result of his efforts) were taken with her little kids in tow, in the stockyards, on the streets, all over the city. She used a Rolleiflex twin-lens reflex camera, which, as the celebrated photographer (and Maier enthusiast) Joel Meyerowitz notes, allows its user to unobtrusively capture its subjects – the perfect instrument for an artist as fiercely secretive as Maier. (She rarely gave out her real name to people, often calling herself “V. Smith.”)

Maier’s relations with her employers and their children elicit contradictory responses. A few of the grown-up kids speak of a dark side and violent outbursts; others so revered her that, in her later years, when she was close to homeless, they paid for her rent and storage. It’s likely that Maier became a nanny in part because she was trying to capture a happy childhood she never experienced for herself. But amateur psychologizing doesn’t really resolve her mystery; in some ways, the more we learn about her, the greater the enigma.

Her story seems especially enigmatic because in the modern age we are so inured to the culture of celebrity that it seems impossible to imagine anyone disdaining it. Maier is a great artist who discounted adulation entirely. Her life was a masquerade; her genius, quite literally, was unexposed.