After Hours Virtual Cinema

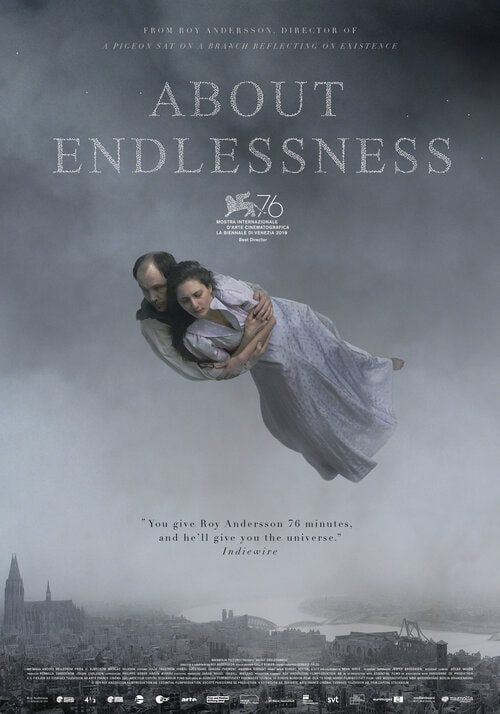

Director: Roy Andersson

Featuring Amanda Davies, Ania Nova, Anja Broms,

Genre(s): Drama, Fantasy

Rating: Not Rated

Runtime: 78 min

In Swedish, with subtitles

Featuring Amanda Davies, Ania Nova, Anja Broms,

Genre(s): Drama, Fantasy

Rating: Not Rated

Runtime: 78 min

In Swedish, with subtitles

“About Endlessness.”

By A.O. Scott | New York Times

In his elegy for William Butler Yeats, W.H. Auden instructed poets to “sing of human unsuccess/in a rapture of distress.” The Swedish filmmaker Roy Andersson may be the great cinematic bard of failure and futility, though his version of rapture is a decidedly low-key affair. “About Endlessness,” his new feature, is at once gloomy and vivid, 76 minutes worth of vignettes that are individually somber and cumulatively exhilarating.

Anyone who has seen his “You, the Living” (2009) or “A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence” (2015) will be primed for this paradox. Viewers lucky enough to be discovering Andersson for the first time will receive a concise introduction to his method and sensibility.

This isn’t to say that “About Endlessness” is exactly like the other films. As ever, Andersson favors washed-out colors and lived-in faces, people who move slowly and a camera that doesn’t move at all. Each shot is a kind of sight gag, a visual and philosophical joke with absurdity in the setup and sorrow in the punchline. But this time, more of the jokes are one-liners, in which the premise and the payoff are one and the same.

Some of them are accompanied by the voice of a female narrator who calmly witnesses what we are watching. Her script is like the lyrics of Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”: a simple list of things she’s seen that is full of mystery and portent. “I saw a woman who had a problem with her shoe,” she says, as a woman breaks a high heel against the hard floor of a train station. Later, a man will have a problem with his car. But not everything our invisible guide sees is so mundane. “I saw a man who tried to conquer the world and failed,” she says, as actors playing Adolf Hitler and other high-ranking Nazis gather in a room while bombs fall outside.

She also sees a few people more than once, notably a priest who has lost his faith. He appears first in a dream, hauling a heavy cross up a Stockholm street while being screamed at, flogged and kicked by ordinary-looking modern city residents. The image is jarring because it is incongruous and also completely transparent. We don’t expect to see this particular form of cruelty in this setting, but at the same time we know exactly what it means.

Later, the priest will visit a psychiatrist, an encounter echoed in a later meeting between a dentist and a patient who refuses anesthesia. He’s afraid of needles, he explains, before his howls of pain drive the doctor out of the office and into a bar downstairs. Not that liquor is much of a palliative. The pain that Andersson diagnoses is incurable.

Though perhaps not entirely untreatable. Against the misery of existence, there is the discipline of art, which can be, in the right hands, a kind of homeopathy. There is something unmistakably tender about the way Andersson regards his mopey, weary, self-defeating characters, most of whom are as gray and lumpy as the clouds that hover over them. They are the kind company that misery loves, and therefore a source of unexpected consolation.

By A.O. Scott | New York Times

In his elegy for William Butler Yeats, W.H. Auden instructed poets to “sing of human unsuccess/in a rapture of distress.” The Swedish filmmaker Roy Andersson may be the great cinematic bard of failure and futility, though his version of rapture is a decidedly low-key affair. “About Endlessness,” his new feature, is at once gloomy and vivid, 76 minutes worth of vignettes that are individually somber and cumulatively exhilarating.

Anyone who has seen his “You, the Living” (2009) or “A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence” (2015) will be primed for this paradox. Viewers lucky enough to be discovering Andersson for the first time will receive a concise introduction to his method and sensibility.

This isn’t to say that “About Endlessness” is exactly like the other films. As ever, Andersson favors washed-out colors and lived-in faces, people who move slowly and a camera that doesn’t move at all. Each shot is a kind of sight gag, a visual and philosophical joke with absurdity in the setup and sorrow in the punchline. But this time, more of the jokes are one-liners, in which the premise and the payoff are one and the same.

Some of them are accompanied by the voice of a female narrator who calmly witnesses what we are watching. Her script is like the lyrics of Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”: a simple list of things she’s seen that is full of mystery and portent. “I saw a woman who had a problem with her shoe,” she says, as a woman breaks a high heel against the hard floor of a train station. Later, a man will have a problem with his car. But not everything our invisible guide sees is so mundane. “I saw a man who tried to conquer the world and failed,” she says, as actors playing Adolf Hitler and other high-ranking Nazis gather in a room while bombs fall outside.

She also sees a few people more than once, notably a priest who has lost his faith. He appears first in a dream, hauling a heavy cross up a Stockholm street while being screamed at, flogged and kicked by ordinary-looking modern city residents. The image is jarring because it is incongruous and also completely transparent. We don’t expect to see this particular form of cruelty in this setting, but at the same time we know exactly what it means.

Later, the priest will visit a psychiatrist, an encounter echoed in a later meeting between a dentist and a patient who refuses anesthesia. He’s afraid of needles, he explains, before his howls of pain drive the doctor out of the office and into a bar downstairs. Not that liquor is much of a palliative. The pain that Andersson diagnoses is incurable.

Though perhaps not entirely untreatable. Against the misery of existence, there is the discipline of art, which can be, in the right hands, a kind of homeopathy. There is something unmistakably tender about the way Andersson regards his mopey, weary, self-defeating characters, most of whom are as gray and lumpy as the clouds that hover over them. They are the kind company that misery loves, and therefore a source of unexpected consolation.