Reviewed by Jordan Hoffman – The Guardian

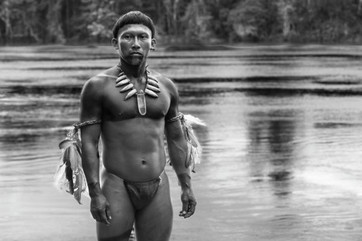

“You are nothing but a white!” So shouts indigenous Amazonian shaman Karamakate (Nilbio Torres) to the seemingly on-the-level but still suspicious German scientist/explorer Theodor (Jan Bijvoet) in Ciro Guerra’s enthralling, politically tinged, psychedelic, historical adventure film Embrace of the Serpent. Reversing the perspective of more familiar movies such as Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo or Roland Joffé’s The Mission, Embrace of the Serpent’s snaky crawl up the river investigates imperialism’s cultural pollution from the inside out, with the mystical Karamakate as a reluctant tour guide in two time periods.

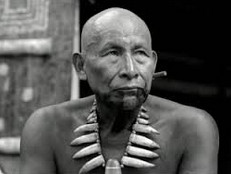

One of the film’s many exciting features is how it slowly cuts between parallel expeditions. Theodor, accompanied by a westernised local, arrives in a canoe, sick with fever. Begrudgingly, the loincloth-wearing Karamakate nurses him back to health by regularly blasting massive doses of white powder (“the sun’s semen”) up his nose. It is 1909 and Theodor is searching for something called the yakruna flower, the only thing that can cure him. Many years later (the exact date’s revelation is something of an unexpected plot turn), an American botanist, Evans (Brionne Davis), paddles up to a much older Karamakate (Antonio Bolívar) hoping to finish Theodor’s work. Evans has a book of Theodor’s final trek, which his aide sent back to Europe, as he did not survive the jungle. The book includes an image of Karamakate, which he refers to as his chullachaqui, a native term for hollow spirit.

The older Karamakate is a broken man who has forgotten the customs of his own people (“Now they are just pictures on rocks,” he laments, looking at petroglyphs) but he agrees to help Evans look for yakruna. When Evans describes himself as someone who has devoted himself to plants, Karamakate counters that this is the first reasonable thing he’s ever heard a white man say.

If this theme of “noble savage” seems a bit passé, know that you are in good hands with Ciro Guerra. The bulk of the film is devoted to dreamlike exploration, observing the folklore of individual tribes and learning about their greater spiritual belief system. A marvellous side trip stumbles upon a Spanish mission, both in 1909 and later. Our first visit, at the height of Colombia’s rubber wars, presents a lone, slightly sadistic priest “saving the souls” of orphaned boys with the lash and scrubbing them of their native language. Our party only dips in for the night, rowing away when things get a bit Lord of the Flies. The decades-later return shows the children grown into a surreal Apocalypse Now scenario. Their society has pieced together scraps of Catholicism and their forgotten indigenous culture creating, as a demoralised Karamakate puts it, the worst of two worlds.

While this bombastic sequence (which includes a rather literal interpretation of the “body of Christ”) takes the familiar “don’t play God” attitude concerning emerging societies (a position familiar to anyone who has seen more than one episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation), an earlier moment puts some spin on the notion of cultural interference. When Theodor realises his compass has been nicked by tribal children, he’s about to resort to violence to get it back. “These people navigate by the moon and stars,” he argues to Karamakate, exuding the misdirected good will of the privileged westerner. “Who are you to withhold knowledge?” Karamakate spits back. You are nothing but a white.

Arriving full circle is appropriate for a film of twin voyages, and Embrace of the Serpent finds its port in a fitting but far-out place. A little post-screening research shows that the two westerners are, indeed, based on real people, even if the yakruna plant is fiction. Richard Evans Schultes’ work in the Amazon exceeded the secretive purposes shown in the film. His research led to important developments in the cultivation of rubber and medicine, and to crucial breakthroughs in psychedelics. In 1979, he and Dr Albert Hofmann, discoverer of LSD, published a book called Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers. Embrace of the Serpent is photographed in shimmering black and white save for one mind-bending scene in explosive colour.

Enough can’t be said about the character Karamakate, in both his old and new versions. He’s a vision of pride and of tragedy, a sorcerer and a saint but also just a man facing the unstoppable current of history. He is wise, but not above laughing when a know-it-all white guy is acting foolishly. Good luck finding a richer, more fascinating character than he at the movies this year.

When I first saw the film at Cannes (where it won the top prize at the Director’s Fortnight sidebar), it was the middle of a hot day during a sleep-deprived week. The atmospheric music, unhurried pace and the accompanying sound of water lapping against the side of a canoe had me convinced that I must have nodded off at some point during its more-than-two-hour run time. Watching the film again in New York for its theatrical release, timed for the Oscars (where it is nominated for best foreign language film), I was surprised to find that, no, I hadn’t dozed during that scorching day in the south of France. Ciro Guerra’s gorgeous picture just has that ripped-from-your-dreams sensibility, where surprising turns float alongside a story you feel like you’ve known your whole life. Embrace of the Serpent is the type of film we’re always searching for, yet seems so obvious once we’ve found it.

A DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Member

“You are nothing but a white!” So shouts indigenous Amazonian shaman Karamakate (Nilbio Torres) to the seemingly on-the-level but still suspicious German scientist/explorer Theodor (Jan Bijvoet) in Ciro Guerra’s enthralling, politically tinged, psychedelic, historical adventure film Embrace of the Serpent. Reversing the perspective of more familiar movies such as Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo or Roland Joffé’s The Mission, Embrace of the Serpent’s snaky crawl up the river investigates imperialism’s cultural pollution from the inside out, with the mystical Karamakate as a reluctant tour guide in two time periods.

One of the film’s many exciting features is how it slowly cuts between parallel expeditions. Theodor, accompanied by a westernised local, arrives in a canoe, sick with fever. Begrudgingly, the loincloth-wearing Karamakate nurses him back to health by regularly blasting massive doses of white powder (“the sun’s semen”) up his nose. It is 1909 and Theodor is searching for something called the yakruna flower, the only thing that can cure him. Many years later (the exact date’s revelation is something of an unexpected plot turn), an American botanist, Evans (Brionne Davis), paddles up to a much older Karamakate (Antonio Bolívar) hoping to finish Theodor’s work. Evans has a book of Theodor’s final trek, which his aide sent back to Europe, as he did not survive the jungle. The book includes an image of Karamakate, which he refers to as his chullachaqui, a native term for hollow spirit.

The older Karamakate is a broken man who has forgotten the customs of his own people (“Now they are just pictures on rocks,” he laments, looking at petroglyphs) but he agrees to help Evans look for yakruna. When Evans describes himself as someone who has devoted himself to plants, Karamakate counters that this is the first reasonable thing he’s ever heard a white man say.

If this theme of “noble savage” seems a bit passé, know that you are in good hands with Ciro Guerra. The bulk of the film is devoted to dreamlike exploration, observing the folklore of individual tribes and learning about their greater spiritual belief system. A marvellous side trip stumbles upon a Spanish mission, both in 1909 and later. Our first visit, at the height of Colombia’s rubber wars, presents a lone, slightly sadistic priest “saving the souls” of orphaned boys with the lash and scrubbing them of their native language. Our party only dips in for the night, rowing away when things get a bit Lord of the Flies. The decades-later return shows the children grown into a surreal Apocalypse Now scenario. Their society has pieced together scraps of Catholicism and their forgotten indigenous culture creating, as a demoralised Karamakate puts it, the worst of two worlds.

While this bombastic sequence (which includes a rather literal interpretation of the “body of Christ”) takes the familiar “don’t play God” attitude concerning emerging societies (a position familiar to anyone who has seen more than one episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation), an earlier moment puts some spin on the notion of cultural interference. When Theodor realises his compass has been nicked by tribal children, he’s about to resort to violence to get it back. “These people navigate by the moon and stars,” he argues to Karamakate, exuding the misdirected good will of the privileged westerner. “Who are you to withhold knowledge?” Karamakate spits back. You are nothing but a white.

Arriving full circle is appropriate for a film of twin voyages, and Embrace of the Serpent finds its port in a fitting but far-out place. A little post-screening research shows that the two westerners are, indeed, based on real people, even if the yakruna plant is fiction. Richard Evans Schultes’ work in the Amazon exceeded the secretive purposes shown in the film. His research led to important developments in the cultivation of rubber and medicine, and to crucial breakthroughs in psychedelics. In 1979, he and Dr Albert Hofmann, discoverer of LSD, published a book called Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers. Embrace of the Serpent is photographed in shimmering black and white save for one mind-bending scene in explosive colour.

Enough can’t be said about the character Karamakate, in both his old and new versions. He’s a vision of pride and of tragedy, a sorcerer and a saint but also just a man facing the unstoppable current of history. He is wise, but not above laughing when a know-it-all white guy is acting foolishly. Good luck finding a richer, more fascinating character than he at the movies this year.

When I first saw the film at Cannes (where it won the top prize at the Director’s Fortnight sidebar), it was the middle of a hot day during a sleep-deprived week. The atmospheric music, unhurried pace and the accompanying sound of water lapping against the side of a canoe had me convinced that I must have nodded off at some point during its more-than-two-hour run time. Watching the film again in New York for its theatrical release, timed for the Oscars (where it is nominated for best foreign language film), I was surprised to find that, no, I hadn’t dozed during that scorching day in the south of France. Ciro Guerra’s gorgeous picture just has that ripped-from-your-dreams sensibility, where surprising turns float alongside a story you feel like you’ve known your whole life. Embrace of the Serpent is the type of film we’re always searching for, yet seems so obvious once we’ve found it.

A DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Member