September 27 | 7:30 pm

CAST & CREW

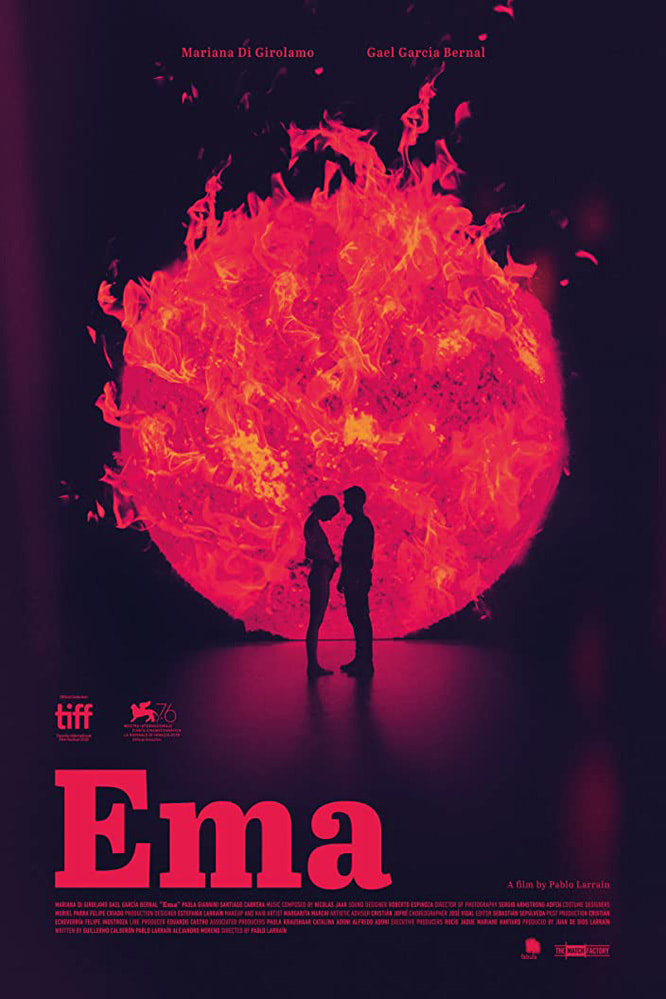

Directed by Pablo Larraín

Starring: Mariana Di Girolamo, Gael García Bernal and Paola Giannini

In Spanish with English Subtitles

Rated R | Running Time: 107 min

Directed by Pablo Larraín

Starring: Mariana Di Girolamo, Gael García Bernal and Paola Giannini

In Spanish with English Subtitles

Rated R | Running Time: 107 min

Ema

Reviewed by David Ehrlich | IndieWire

An anarchic, liberated, and contagiously alive character study that feels like it was born out of a three-way between “Amélie,” “Oldboy,” and Gaspar Noé before maturing into a force of nature all its own, Pablo Larraín’s “Ema” doesn’t always dance to a clear or recognizable beat, but anybody willing to get on its wavelength will be rewarded with one of the year’s most dynamic and electrifying films. Which isn’t to suggest the movie — Larraín’s first since the one-two punch of “Neruda” and “Jackie” in 2016 — doesn’t grab you from the moment it starts, only that it keeps you on your toes for a little while before you can figure out the steps, and it never lets you take the lead.

Or maybe the film’s initial veil of impenetrability would be more accurately likened to the billowing smoke that obfuscates a burning car wreck. At least the identity of the firestarter is never in doubt. Her name is Ema, she’s a Reggaeton dancer in her late twenties, and she’s first introduced walking through the pre-dawn streets of Valparaiso with a flamethrower strapped to her back. You’re drawn to her right away, and not just because gasoline is leaking down her back. It’s the inverted tidal wave of bleached-blonde hair; the leopard-print belly shirt; the hawk-like hunger (for we-don’t-know-what) that makes everyone she looks at seem like prey. It’s like every other person on Earth is sleeping, and she’s out there blazing her own trail.

But Ema, played by Mariana Di Girolamo in the kind of unforgettably self-possessed breakthrough performance that could forge her to this role forever, isn’t quite as free as she seems. The details are fuzzy. Something about a son that’s no longer under her custody. A social worker speaks to Ema in a way that feels… unusually heated. “Surely he’s been adopted by another mom who’s better than you!” she yells. Larráin repeatedly and frustratingly interrupts our first extended glimpse of Ema in her element — she bobbles around with the rest of her dance troupe against the backdrop of a solar flare as Nicolas Jaar’s warm ambient score pulsates over the soundtrack — with expository cut-aways to fights she’s had with her choreographer husband, Gastón (a great, petulant Gael García Bernal). The sequence refuses any sort of rhythm; it’s as if we’re inside Ema’s head and subject to all the thoughts that are taking her out of the moment.

And hot damn the things Ema and Gastón say to each other when they argue, each of them hurling the most incredibly hurtful insults straight into the lens of Sergio Armstrong’s camera. He’s infertile, she’s a monster, and neither of them could stand the 7-year-old kid they adopted together and just gave back. But if little Polo (Cristián Suárez) was such a terror — he locked their friend’s cat in the freezer! — then why are they so broken up about the decision? Maybe it’s guilt over a foster system that’s prejudiced against Colombian and Venezuelan kids, or maybe Ema just has a primal need to mother something. Either way, there doesn’t seem to be much of a way forward. “You have to do what a lizard does when their tail gets cut off,” someone suggests. But they can’t grow a new kid. That’s the problem. And besides, Gastón notes, lizards don’t just sprout a new appendage. First, “they get all disoriented and f***ed-up.”

Larraín does eventually carve out a clear(ish) plot, but most of “Ema” is about someone — someone who’s lost a valuable part of themselves, and tries to find it again by following her own unquenchable life force — getting all disoriented and messed-up. It’s not as depressing as it sounds. In fact, it’s not depressing at all. This isn’t a sad-faced social drama about an unprepared mother who throws herself at the mercy of the courts and promises to reform her wicked ways, this is a feral and deliriously non-conformist riot of sex and rage; it’s the spray-painted portrait of a torrential young woman who refuses to water herself down.

Ema, who hardly goes anywhere without her free-loving, body-rocking, do-not-f***-with-us sisterhood of the traveling spanx, has no interest in changing. In being a “good” girl. That would be like Furiosa going back to the way things were under Immortan Joe. Men have to meet her on her terms, and her son — if she can ever call him that again — is the only one who gets free reign. Without any feminist platitudes, but tons of collateral damage, Ema is going to remake the world in her own image, and Di Girolamo’s combustible performance leaves no doubt that she’s able to do just that. That she’ll be able to pull off a vague but demented master plan that starts with seducing everyone in sight.

Larraín never spells things out, and it’s entirely possible that a certain amount of social context might be lost for non-Chileans. Story is never the main focus here, as the director lavishes more attention on the day-glo sunsets of Valparaíso, the hyper-saturated city streets, and the palpable steam that rises off of them whenever Ema and her friends decide to screw around. The film is carried along by elemental forces and emotional undercurrents; scenes don’t spur the narrative forward so much as they work to melt the space between hearts and bodies. Eventually, the way Ema moves — the way she twitches her nose at someone or straddles them into a fluorescent sex montage — becomes the story.

“I teach freedom,” she tells someone interviewing her for a job at an elementary school, and she’s not lying. She knows how to wiggle out of the mess she’s made for herself, but she’ll have to teach other people to go along with it. That process can be stultifying at first, especially in the early stretches where Ema is even more frustrated than we are. But once she starts working things out, it’s like Di Girolamo endows Larraín with new life, and the movie starts spraying raw feeling in all directions. One wildly unpredictable scene gyrates into another as “Ema” builds towards a magical, swing-for-the-fences ending that its namesake has been telegraphing for us every step of the way. “The system is made to cut people like you out!” Ema’s social worker tells her. But the fact of the matter is that there really isn’t anyone quite like Ema.

Reviewed by David Ehrlich | IndieWire

An anarchic, liberated, and contagiously alive character study that feels like it was born out of a three-way between “Amélie,” “Oldboy,” and Gaspar Noé before maturing into a force of nature all its own, Pablo Larraín’s “Ema” doesn’t always dance to a clear or recognizable beat, but anybody willing to get on its wavelength will be rewarded with one of the year’s most dynamic and electrifying films. Which isn’t to suggest the movie — Larraín’s first since the one-two punch of “Neruda” and “Jackie” in 2016 — doesn’t grab you from the moment it starts, only that it keeps you on your toes for a little while before you can figure out the steps, and it never lets you take the lead.

Or maybe the film’s initial veil of impenetrability would be more accurately likened to the billowing smoke that obfuscates a burning car wreck. At least the identity of the firestarter is never in doubt. Her name is Ema, she’s a Reggaeton dancer in her late twenties, and she’s first introduced walking through the pre-dawn streets of Valparaiso with a flamethrower strapped to her back. You’re drawn to her right away, and not just because gasoline is leaking down her back. It’s the inverted tidal wave of bleached-blonde hair; the leopard-print belly shirt; the hawk-like hunger (for we-don’t-know-what) that makes everyone she looks at seem like prey. It’s like every other person on Earth is sleeping, and she’s out there blazing her own trail.

But Ema, played by Mariana Di Girolamo in the kind of unforgettably self-possessed breakthrough performance that could forge her to this role forever, isn’t quite as free as she seems. The details are fuzzy. Something about a son that’s no longer under her custody. A social worker speaks to Ema in a way that feels… unusually heated. “Surely he’s been adopted by another mom who’s better than you!” she yells. Larráin repeatedly and frustratingly interrupts our first extended glimpse of Ema in her element — she bobbles around with the rest of her dance troupe against the backdrop of a solar flare as Nicolas Jaar’s warm ambient score pulsates over the soundtrack — with expository cut-aways to fights she’s had with her choreographer husband, Gastón (a great, petulant Gael García Bernal). The sequence refuses any sort of rhythm; it’s as if we’re inside Ema’s head and subject to all the thoughts that are taking her out of the moment.

And hot damn the things Ema and Gastón say to each other when they argue, each of them hurling the most incredibly hurtful insults straight into the lens of Sergio Armstrong’s camera. He’s infertile, she’s a monster, and neither of them could stand the 7-year-old kid they adopted together and just gave back. But if little Polo (Cristián Suárez) was such a terror — he locked their friend’s cat in the freezer! — then why are they so broken up about the decision? Maybe it’s guilt over a foster system that’s prejudiced against Colombian and Venezuelan kids, or maybe Ema just has a primal need to mother something. Either way, there doesn’t seem to be much of a way forward. “You have to do what a lizard does when their tail gets cut off,” someone suggests. But they can’t grow a new kid. That’s the problem. And besides, Gastón notes, lizards don’t just sprout a new appendage. First, “they get all disoriented and f***ed-up.”

Larraín does eventually carve out a clear(ish) plot, but most of “Ema” is about someone — someone who’s lost a valuable part of themselves, and tries to find it again by following her own unquenchable life force — getting all disoriented and messed-up. It’s not as depressing as it sounds. In fact, it’s not depressing at all. This isn’t a sad-faced social drama about an unprepared mother who throws herself at the mercy of the courts and promises to reform her wicked ways, this is a feral and deliriously non-conformist riot of sex and rage; it’s the spray-painted portrait of a torrential young woman who refuses to water herself down.

Ema, who hardly goes anywhere without her free-loving, body-rocking, do-not-f***-with-us sisterhood of the traveling spanx, has no interest in changing. In being a “good” girl. That would be like Furiosa going back to the way things were under Immortan Joe. Men have to meet her on her terms, and her son — if she can ever call him that again — is the only one who gets free reign. Without any feminist platitudes, but tons of collateral damage, Ema is going to remake the world in her own image, and Di Girolamo’s combustible performance leaves no doubt that she’s able to do just that. That she’ll be able to pull off a vague but demented master plan that starts with seducing everyone in sight.

Larraín never spells things out, and it’s entirely possible that a certain amount of social context might be lost for non-Chileans. Story is never the main focus here, as the director lavishes more attention on the day-glo sunsets of Valparaíso, the hyper-saturated city streets, and the palpable steam that rises off of them whenever Ema and her friends decide to screw around. The film is carried along by elemental forces and emotional undercurrents; scenes don’t spur the narrative forward so much as they work to melt the space between hearts and bodies. Eventually, the way Ema moves — the way she twitches her nose at someone or straddles them into a fluorescent sex montage — becomes the story.

“I teach freedom,” she tells someone interviewing her for a job at an elementary school, and she’s not lying. She knows how to wiggle out of the mess she’s made for herself, but she’ll have to teach other people to go along with it. That process can be stultifying at first, especially in the early stretches where Ema is even more frustrated than we are. But once she starts working things out, it’s like Di Girolamo endows Larraín with new life, and the movie starts spraying raw feeling in all directions. One wildly unpredictable scene gyrates into another as “Ema” builds towards a magical, swing-for-the-fences ending that its namesake has been telegraphing for us every step of the way. “The system is made to cut people like you out!” Ema’s social worker tells her. But the fact of the matter is that there really isn’t anyone quite like Ema.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$7.00 Members | $11.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue | Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 | classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs

$7.00 Members | $11.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue | Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 | classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs