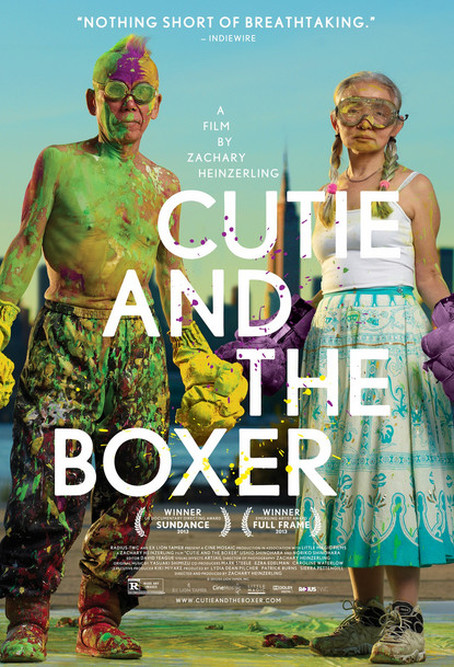

FILM DETAILS

Documentary by Zachary Heinzerling

Featuring Ushio & Noriko Shinohara

Running time: 82 minutes

Rated R

Reviewed by Betsy Sharkey – LA Times

There is a scene early in "Cutie and the Boxer" of 80-year-old Ushio Shinohara brushing his teeth, although attacking his teeth would come closer to the ferocity with which he goes at the job.

It's a small detail, but like so many in Zachary Heinzerling's remarkable documentary debut, a carefully chosen one. The director wants us to understand Shinohara is a fierce man.

An artist, Shinohara is known for his "boxing" technique, part of his action painting style that is arguably performance art by itself. We see a demonstration, the boxing gloves dipped into, then dripping with paint, the man hurling himself at a huge canvas — punching, whirling, punching again and again, creating an explosion of imagery and color in real time. Shinohara's body and the canvas are both streaked when he's done, the man exhausted, the art vibrating with energy.

As riveting as Shinohara is, the filmmaker is only setting the groundwork for the real artist he is interested in — Noriko, Shinohara's wife of 40 years.

Unlike her frenetic husband, Noriko, 59, is the rock in the relationship, the lion tamer. The lion keeper. Cutting the fish for a meal, sorting through old canvases with Shinohara for a display of his work the Guggenheim is considering, worrying over the bills that pile up. The artist is still struggling and the artist's assistant is too. At one point Shinohara says dismissively that her role is to serve the artist, so the artist can serve the art.

It is a remarkably unfiltered moment that speaks as much to human relationships as it does to the artistic life. In "Cutie," Heinzerling gives us both brilliantly; it earned him the top directing award at Sundance earlier this year.

That so much of the personal makes it on-screen is thanks to a filmmaker who is fearless and invisible. Working as director and cinematographer, Heinzerling earned the couple's trust before turning his camera on their days and nights. But once that camera was running, there was no blinking, no turning away.

The Shinoharas' past is built out of old footage and photos. There are shots of the young Shinohara in Tokyo in the '60s, sporting a mohawk as he made his manic art on the streets. Then in New York, we see him as a member of the avant-garde scene, rubbing shoulders with Andy Warhol among others. The tone shifts to footage of late nights and too much drink — Shinohara regaling his buddies. It would lead to a very difficult alcohol-drenched stretch for the artist.

When the focus shifts to Noriko, she is 19 and newly arrived in New York on a student visa. Her quick absorption into Shinohara's scene, his life, leads within a year to their marriage and a baby. Her artistic dreams are soon overrun by taking care of Shinohara and their son. There is a telling shot of those early days, Noriko in her artist smock, working on a canvas in a corner of the studio.

It is in plumbing the tension between his dreams and hers that the film is at its most intriguing. Noriko had only recently picked up the brush again when Heinzerling began filming. It was a director's gift. Years of pent-up emotions began flowing through a new, fertile stream of art — watercolor panels that tell the story of a naked superhero called Cutie, her braids a perky version of Noriko's silver ones, and the Boxer she must face down. It is a refined comic-book style, leavened by the inky-blue softness of the style. But like Noriko, you can't let Cutie's perky braids fool you. She is fierce as she battles her nemesis.

Heinzerling not only shows Noriko making art, he's animated it, using it throughout the film to reveal the real contours of Noriko's journey.

Money issues are as much a factor as the artistic tensions. There is a crazy section that follows Shinohara's spur-of-the-moment decision to pack up some of his sculpture and take it Japan to sell. It is a DIY moment of such strangeness that the clip would probably be a YouTube sensation.

An upcoming gallery show of Shinohara's work also helps propels the artist and the film. At some point in the discussions with the gallery owner, Noriko mentions her work, and the ground shifts once again.

For all of the eccentricities that come in any telling of an artist's life, "Cutie and

the Boxer's" real magic is in so beautifully telling a familiar story of husbands and wives. The Shinoharas' floors may be splattered by years of inspiration, their rooms stacked with canvases, but the ways in which time and circumstance, success and failure, disappointment and joy frame and change their relationship — that is universal.

There is a scene early in "Cutie and the Boxer" of 80-year-old Ushio Shinohara brushing his teeth, although attacking his teeth would come closer to the ferocity with which he goes at the job.

It's a small detail, but like so many in Zachary Heinzerling's remarkable documentary debut, a carefully chosen one. The director wants us to understand Shinohara is a fierce man.

An artist, Shinohara is known for his "boxing" technique, part of his action painting style that is arguably performance art by itself. We see a demonstration, the boxing gloves dipped into, then dripping with paint, the man hurling himself at a huge canvas — punching, whirling, punching again and again, creating an explosion of imagery and color in real time. Shinohara's body and the canvas are both streaked when he's done, the man exhausted, the art vibrating with energy.

As riveting as Shinohara is, the filmmaker is only setting the groundwork for the real artist he is interested in — Noriko, Shinohara's wife of 40 years.

Unlike her frenetic husband, Noriko, 59, is the rock in the relationship, the lion tamer. The lion keeper. Cutting the fish for a meal, sorting through old canvases with Shinohara for a display of his work the Guggenheim is considering, worrying over the bills that pile up. The artist is still struggling and the artist's assistant is too. At one point Shinohara says dismissively that her role is to serve the artist, so the artist can serve the art.

It is a remarkably unfiltered moment that speaks as much to human relationships as it does to the artistic life. In "Cutie," Heinzerling gives us both brilliantly; it earned him the top directing award at Sundance earlier this year.

That so much of the personal makes it on-screen is thanks to a filmmaker who is fearless and invisible. Working as director and cinematographer, Heinzerling earned the couple's trust before turning his camera on their days and nights. But once that camera was running, there was no blinking, no turning away.

The Shinoharas' past is built out of old footage and photos. There are shots of the young Shinohara in Tokyo in the '60s, sporting a mohawk as he made his manic art on the streets. Then in New York, we see him as a member of the avant-garde scene, rubbing shoulders with Andy Warhol among others. The tone shifts to footage of late nights and too much drink — Shinohara regaling his buddies. It would lead to a very difficult alcohol-drenched stretch for the artist.

When the focus shifts to Noriko, she is 19 and newly arrived in New York on a student visa. Her quick absorption into Shinohara's scene, his life, leads within a year to their marriage and a baby. Her artistic dreams are soon overrun by taking care of Shinohara and their son. There is a telling shot of those early days, Noriko in her artist smock, working on a canvas in a corner of the studio.

It is in plumbing the tension between his dreams and hers that the film is at its most intriguing. Noriko had only recently picked up the brush again when Heinzerling began filming. It was a director's gift. Years of pent-up emotions began flowing through a new, fertile stream of art — watercolor panels that tell the story of a naked superhero called Cutie, her braids a perky version of Noriko's silver ones, and the Boxer she must face down. It is a refined comic-book style, leavened by the inky-blue softness of the style. But like Noriko, you can't let Cutie's perky braids fool you. She is fierce as she battles her nemesis.

Heinzerling not only shows Noriko making art, he's animated it, using it throughout the film to reveal the real contours of Noriko's journey.

Money issues are as much a factor as the artistic tensions. There is a crazy section that follows Shinohara's spur-of-the-moment decision to pack up some of his sculpture and take it Japan to sell. It is a DIY moment of such strangeness that the clip would probably be a YouTube sensation.

An upcoming gallery show of Shinohara's work also helps propels the artist and the film. At some point in the discussions with the gallery owner, Noriko mentions her work, and the ground shifts once again.

For all of the eccentricities that come in any telling of an artist's life, "Cutie and

the Boxer's" real magic is in so beautifully telling a familiar story of husbands and wives. The Shinoharas' floors may be splattered by years of inspiration, their rooms stacked with canvases, but the ways in which time and circumstance, success and failure, disappointment and joy frame and change their relationship — that is universal.