After Hours Virtual Cinema

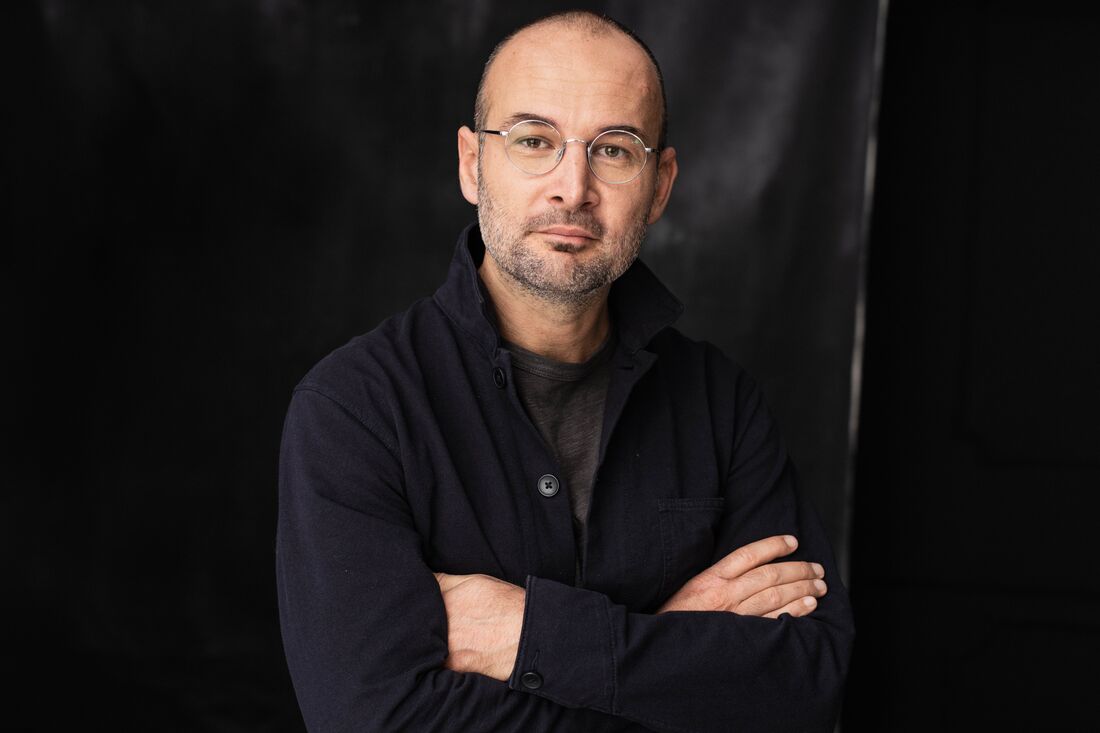

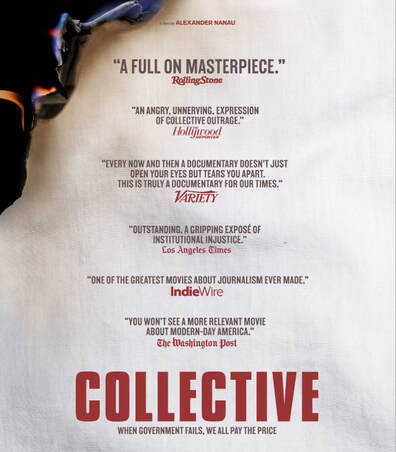

Directed by Alexander Nanau

Genre: Documentary

Running Time: 109 mins.

Not Rated

In Romanian with English Subtitles

Genre: Documentary

Running Time: 109 mins.

Not Rated

In Romanian with English Subtitles

By Jay Weissberg | Variety

Every now and then a documentary doesn’t just open your eyes but tears you apart by exposing a moral rift with resonance far beyond the film’s home country. “Collective,” Alexander Nanau’s explosive observational documentary about unfathomable corruption at the heart of the Romanian medical industry, is such a work. Taken on its own, this chilling exposé should send shockwaves through a system so mired in venality that politicians as well as a large segment of the medical profession thought nothing of letting people die so they could stay in power and ensure their kickbacks. But the corrosive corruption revealed has ramifications far greater than just in Romania, for it’s indicative of a worldwide phenomenon in which people feel so disconnected from others that empathy has been replaced by avarice, and strangers are viewed as abstractions. This is truly a documentary for our times, deserving of widespread exposure.

In 2015, a fire in the Bucharest club Colectiv immediately claimed 27 lives, but 37 more people died during the weeks that followed thanks to inadequate hospital facilities and rampant infections. The shameless lies spouted by the Romanian ministers and the revelations that followed brought down the government, though their time out of power was remarkably brief.

Nanau (“Toto and his Sisters”) began shooting during the early days of the scandal, when journalist Cătălin Tolontan, incongruously writing for the sports newspaper “Gazeta Sporturilor,” started questioning the official stories put out by the Minister of Health Nicolae Bănicioiu, who proclaimed that Romanian hospitals were perfectly prepared for emergencies and every bit as good as ones in Germany.

Tolontan and his investigative team revealed what the government wanted to keep quiet: Not only were the hospitals, even the so-called specialized burn unit, unequipped to handle burn victims, but the disinfectant used in medical facilities nationwide was being diluted to the point of losing all effectiveness at killing bacteria. As if the immediate deaths following the fire weren’t bad enough, parents were watching their children with agonizing injuries die weeks later from preventable infections. One father even testified that a facility in Vienna offered to take his son but the Bucharest hospital refused to sign off on the transfer. As victims kept dying, the Health Ministry claimed they tested the disinfectants and found they were 95% effective, a reprehensible lie concocted to make the scandal go away.

Instead, the journalists traced the antibacterial liquids to Hexi Pharma and its owner, Dan Condrea, who had the solutions diluted before selling them to hospitals, where they were watered down even further. In a complete betrayal of the Hippocratic Oath, medical professionals were in on it all, pocketing bribe money that was going up and down the chain of command. One brave doctor had been secretly passing documents on to the State Security Services since 2008, alerting them to what was going on, but nothing was done and Intelligence claimed that eight years of reports had mysteriously gone missing.

The second part of the documentary was shot after massive protests forced a change in the technocrat government. The young new Minister of Health, Vlad Voiculescu, was a patients’ rights advocate and, like most of the new ministers, invested in the kind of transparency previously unseen in the country. He granted the director unprecedented access to private meetings, which means Nanau’s camera was witness to months of inquiries during which Voiculescu uncovered the sickening extent to which Romania’s medical establishment was implicated alongside the former administration. Yet the Minister’s herculean efforts to effect change, his willingness to tell the truth to an infuriated population, were only temporary. By continuing to feed lies to an exhausted and suspicious public, the Social Democrats were voted back into power, stymieing the reforms begun by Voiculescu and his demoralized colleagues.

Few viewers will fail to make unnerving comparisons with their own countries while watching government officials blatantly lie to citizens and then get re-elected into office. One of the brilliant elements of Nanau’s work is how he completely focuses on Romania and this one situation while silently insisting on it being seen as a reflection of a worldwide sickness. It’s not just the lies, spouted so often that truth seems an antiquated concept, but the total absence of compassion. There’s a line in “Nothing More,” a song in the film by the Alternate Routes that perfectly sums up the situation: “We are how we treat each other when the day is done.” The day is done, night has fallen, and fewer and fewer people seem concerned by how bleak the morning will be.

Mixed into the investigative section and sequences with the Minister are scenes with Tedy Ursuleanu, a woman who was at Colectiv the night of the fire and sustained severe burns all over her head and body. She survived with significant scarring and the loss of a hand, yet rather than shun the light she’s become a symbol of the tragedy thanks to her resilience and refusal to let this simply fade away. In keeping with the rigorously observational approach he’s always used, Nanau doesn’t interview Ursuleanu or any of the other people in the film: He shot for 14 months and then edited for another 18 months, locating the essential details in all that footage in order to expose the struggle to reassert a humanity made anemic by systemic corruption. At least for the short term, the prognosis isn’t good, but “Collective” will surely help.

Available now through July 31st!

Every now and then a documentary doesn’t just open your eyes but tears you apart by exposing a moral rift with resonance far beyond the film’s home country. “Collective,” Alexander Nanau’s explosive observational documentary about unfathomable corruption at the heart of the Romanian medical industry, is such a work. Taken on its own, this chilling exposé should send shockwaves through a system so mired in venality that politicians as well as a large segment of the medical profession thought nothing of letting people die so they could stay in power and ensure their kickbacks. But the corrosive corruption revealed has ramifications far greater than just in Romania, for it’s indicative of a worldwide phenomenon in which people feel so disconnected from others that empathy has been replaced by avarice, and strangers are viewed as abstractions. This is truly a documentary for our times, deserving of widespread exposure.

In 2015, a fire in the Bucharest club Colectiv immediately claimed 27 lives, but 37 more people died during the weeks that followed thanks to inadequate hospital facilities and rampant infections. The shameless lies spouted by the Romanian ministers and the revelations that followed brought down the government, though their time out of power was remarkably brief.

Nanau (“Toto and his Sisters”) began shooting during the early days of the scandal, when journalist Cătălin Tolontan, incongruously writing for the sports newspaper “Gazeta Sporturilor,” started questioning the official stories put out by the Minister of Health Nicolae Bănicioiu, who proclaimed that Romanian hospitals were perfectly prepared for emergencies and every bit as good as ones in Germany.

Tolontan and his investigative team revealed what the government wanted to keep quiet: Not only were the hospitals, even the so-called specialized burn unit, unequipped to handle burn victims, but the disinfectant used in medical facilities nationwide was being diluted to the point of losing all effectiveness at killing bacteria. As if the immediate deaths following the fire weren’t bad enough, parents were watching their children with agonizing injuries die weeks later from preventable infections. One father even testified that a facility in Vienna offered to take his son but the Bucharest hospital refused to sign off on the transfer. As victims kept dying, the Health Ministry claimed they tested the disinfectants and found they were 95% effective, a reprehensible lie concocted to make the scandal go away.

Instead, the journalists traced the antibacterial liquids to Hexi Pharma and its owner, Dan Condrea, who had the solutions diluted before selling them to hospitals, where they were watered down even further. In a complete betrayal of the Hippocratic Oath, medical professionals were in on it all, pocketing bribe money that was going up and down the chain of command. One brave doctor had been secretly passing documents on to the State Security Services since 2008, alerting them to what was going on, but nothing was done and Intelligence claimed that eight years of reports had mysteriously gone missing.

The second part of the documentary was shot after massive protests forced a change in the technocrat government. The young new Minister of Health, Vlad Voiculescu, was a patients’ rights advocate and, like most of the new ministers, invested in the kind of transparency previously unseen in the country. He granted the director unprecedented access to private meetings, which means Nanau’s camera was witness to months of inquiries during which Voiculescu uncovered the sickening extent to which Romania’s medical establishment was implicated alongside the former administration. Yet the Minister’s herculean efforts to effect change, his willingness to tell the truth to an infuriated population, were only temporary. By continuing to feed lies to an exhausted and suspicious public, the Social Democrats were voted back into power, stymieing the reforms begun by Voiculescu and his demoralized colleagues.

Few viewers will fail to make unnerving comparisons with their own countries while watching government officials blatantly lie to citizens and then get re-elected into office. One of the brilliant elements of Nanau’s work is how he completely focuses on Romania and this one situation while silently insisting on it being seen as a reflection of a worldwide sickness. It’s not just the lies, spouted so often that truth seems an antiquated concept, but the total absence of compassion. There’s a line in “Nothing More,” a song in the film by the Alternate Routes that perfectly sums up the situation: “We are how we treat each other when the day is done.” The day is done, night has fallen, and fewer and fewer people seem concerned by how bleak the morning will be.

Mixed into the investigative section and sequences with the Minister are scenes with Tedy Ursuleanu, a woman who was at Colectiv the night of the fire and sustained severe burns all over her head and body. She survived with significant scarring and the loss of a hand, yet rather than shun the light she’s become a symbol of the tragedy thanks to her resilience and refusal to let this simply fade away. In keeping with the rigorously observational approach he’s always used, Nanau doesn’t interview Ursuleanu or any of the other people in the film: He shot for 14 months and then edited for another 18 months, locating the essential details in all that footage in order to expose the struggle to reassert a humanity made anemic by systemic corruption. At least for the short term, the prognosis isn’t good, but “Collective” will surely help.

Available now through July 31st!