CAST & CREW

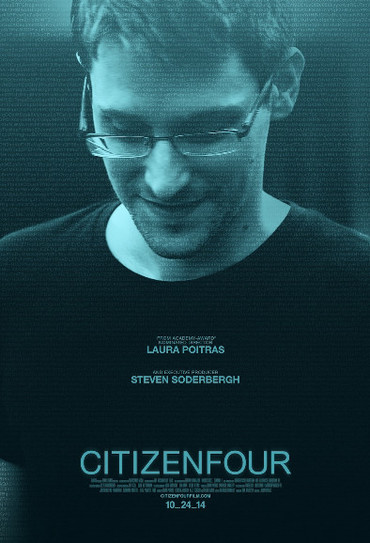

Featuring Laura Poitras,

Edward Snowden & Glenn Greenwald

A Documentary Directed by Laura Poitras

Rated R 114 Mins.

Featuring Laura Poitras,

Edward Snowden & Glenn Greenwald

A Documentary Directed by Laura Poitras

Rated R 114 Mins.

Reviewed by Ty Burr - Boston Globe

Sometimes the most momentous historical events are utterly banal in their unfolding — say, three people looking at memorandums in a generic high-rise hotel room. “Citizenfour” is a documentary about the National Security Agency systems administrator-turned-leaker Edward Snowden at the exact moment he leaked, alerting America and the world to the spies in our midst. The movie was made by Laura Poitras as she and fellow journalist Glenn Greenwald met with Snowden in Hong Kong; since all three are not exactly viewed with affection by the US government, the film seems intended as insurance as much as evidence.

“Citzenfour” is prosaic in its presentation and profoundly chilling in its details, and if you think Snowden is a traitor, you should probably see it. If you think he’s a hero, you should probably see it. If you haven’t made up your mind — well, you get the idea. Certainly if you think no one knows whom you’re calling, what you’re texting, or what websites you’re patronizing, you should think again.

Snowden contacted Poitras through encrypted channels in January 2013; the anonymous e-mails, white type on black background, scroll across the screen like messages from a ghost. After the two vetted each other to their satisfaction, Snowden flew in June from his post in Hawaii to Hong Kong, where he and the two journalists prepared the leaked material for publication. Halfway through they were joined by Ewen MacAskill of London’s Guardian.

Their revelations, reported on CNN and in the Washington Post, the Guardian, and Germany’s Der Spiegel, are by now well-known: Verizon, AT&T, and other telecoms opening hundreds of millions of phone records to the NSA; that agency and the FBI tapping directly into the data of Internet companies like Yahoo and Google; the PRISM surveillance program that collects e-mail, texts, voicemails, and video chats of foreigners and US citizens; the massive metadata-mining program called Stellar Wind; the weakening of commercial software encryption programs under pressure from the intelligence community; stealth operations called Dishfire, XKeyscore, Tempora that allowed the US and other members of the “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance (the UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) access to our daily communications (metadata and content); the hacking of the UN’s video conferencing system; and on and on. Tapping German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s phone calls is small potatoes, really. With the NSA’s capacity to monitor 75 percent of all US Internet traffic, it’s you and I who are being watched.

All of this is currently carried out under Presidential Policy Directive 20, signed in secret by President Barack Obama in October 2012. Interviewed by Poitras, William Binney, a former NSA technical director turned whistle-blower, says “a week after 9/11, they began actively spying on everyone in this country.” She also includes CSPAN footage of former NSA chief Keith Alexander denying all of the above before Congress. “We are not authorized to do it and we do not do it,” he says. (There’s a technical term for this: lying.)

That this global incursion of our right to privacy comes to light in the mundane setting captured by “Citizenfour” is both heartening and surreal. The movie is a piece of advocacy, obviously, but it also seems intent on documenting the work of a handful of concerned individuals in correcting what they see as extreme governmental overreach, and to imply that such efforts are not beyond the power of the average citizen.

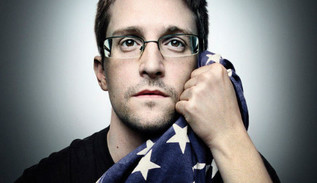

Above all, the movie puts a human face on Edward Snowden, the bespectacled cipher whose guilt, for many, is proved by the fact that he’s currently residing in Moscow courtesy of Vladimir Putin. That development comes in the final third of “Citizenfour”; the first two-thirds bring us close to the man responsible for perhaps the greatest intelligence leak of modern times.

He comes across as young, sane, soft-spoken, intelligent, even slightly dull — driven not by ideology but by his horror at the facts. He’s not a tortured soul like Chelsea (formerly Bradley) Manning or a glory-hound like Julian Assange (who’s glimpsed very briefly here). If anything, Snowden’s the anti-Assange. He looks like half the guys working for Boston.com down the hall from my office.

Snowden knows he’ll be the story, knows we’re drawn to faces instead of numbers, and he’s torn about it. On one hand, he tells Poitras to “paint the target on my back,” so people will know who did this and, more important, why. On the other, he insists that any attention paid to him is a diversion. Since the initial news reports have barely scratched the surface of the tens of thousands of pages of government documents, those revelations will keep coming, and it’s possible their provider may yet fade behind what they tell us.

There are moments of Kafkaesque comedy in “Citizenfour.” After Snowden mentions the room could be tapped via the hotel phone handset and disconnects it, the building’s fire alarm starts beeping ominously. Is it a system test, as the front desk claims? Probably. Possibly. Maybe not. When you’ve worked, as Snowden has, in an office with surveillance drone video feeds on your desktop the way some people have stock tickers, it’s easy to assume someone’s listening. By the final hotel room sessions, Greenwald and Snowden are silently writing their conversations on scraps of paper.

Charged with three criminal counts by the US government — two of them under the 1917 Espionage Act — Snowden ended up marooned at a Moscow airport while bound for South America. He was granted temporary asylum in Russia, recently extended, where he has given interviews to the international press but has otherwise laid low. His most foolish move was appearing with Putin on television in January of this year, prodding the Russian leader on his own use of surveillance — an attempt to level the playing field that backfired and left Snowden looking naïve.

That’s not part of “Citizenfour,” and it probably should be. What’s here is more than enough to get you thinking about a world in which no one gets to have secrets except the agencies that secretly watch us. Snowden’s right: He’s not the story. You are, and what you’re going to do about it.

Sometimes the most momentous historical events are utterly banal in their unfolding — say, three people looking at memorandums in a generic high-rise hotel room. “Citizenfour” is a documentary about the National Security Agency systems administrator-turned-leaker Edward Snowden at the exact moment he leaked, alerting America and the world to the spies in our midst. The movie was made by Laura Poitras as she and fellow journalist Glenn Greenwald met with Snowden in Hong Kong; since all three are not exactly viewed with affection by the US government, the film seems intended as insurance as much as evidence.

“Citzenfour” is prosaic in its presentation and profoundly chilling in its details, and if you think Snowden is a traitor, you should probably see it. If you think he’s a hero, you should probably see it. If you haven’t made up your mind — well, you get the idea. Certainly if you think no one knows whom you’re calling, what you’re texting, or what websites you’re patronizing, you should think again.

Snowden contacted Poitras through encrypted channels in January 2013; the anonymous e-mails, white type on black background, scroll across the screen like messages from a ghost. After the two vetted each other to their satisfaction, Snowden flew in June from his post in Hawaii to Hong Kong, where he and the two journalists prepared the leaked material for publication. Halfway through they were joined by Ewen MacAskill of London’s Guardian.

Their revelations, reported on CNN and in the Washington Post, the Guardian, and Germany’s Der Spiegel, are by now well-known: Verizon, AT&T, and other telecoms opening hundreds of millions of phone records to the NSA; that agency and the FBI tapping directly into the data of Internet companies like Yahoo and Google; the PRISM surveillance program that collects e-mail, texts, voicemails, and video chats of foreigners and US citizens; the massive metadata-mining program called Stellar Wind; the weakening of commercial software encryption programs under pressure from the intelligence community; stealth operations called Dishfire, XKeyscore, Tempora that allowed the US and other members of the “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance (the UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) access to our daily communications (metadata and content); the hacking of the UN’s video conferencing system; and on and on. Tapping German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s phone calls is small potatoes, really. With the NSA’s capacity to monitor 75 percent of all US Internet traffic, it’s you and I who are being watched.

All of this is currently carried out under Presidential Policy Directive 20, signed in secret by President Barack Obama in October 2012. Interviewed by Poitras, William Binney, a former NSA technical director turned whistle-blower, says “a week after 9/11, they began actively spying on everyone in this country.” She also includes CSPAN footage of former NSA chief Keith Alexander denying all of the above before Congress. “We are not authorized to do it and we do not do it,” he says. (There’s a technical term for this: lying.)

That this global incursion of our right to privacy comes to light in the mundane setting captured by “Citizenfour” is both heartening and surreal. The movie is a piece of advocacy, obviously, but it also seems intent on documenting the work of a handful of concerned individuals in correcting what they see as extreme governmental overreach, and to imply that such efforts are not beyond the power of the average citizen.

Above all, the movie puts a human face on Edward Snowden, the bespectacled cipher whose guilt, for many, is proved by the fact that he’s currently residing in Moscow courtesy of Vladimir Putin. That development comes in the final third of “Citizenfour”; the first two-thirds bring us close to the man responsible for perhaps the greatest intelligence leak of modern times.

He comes across as young, sane, soft-spoken, intelligent, even slightly dull — driven not by ideology but by his horror at the facts. He’s not a tortured soul like Chelsea (formerly Bradley) Manning or a glory-hound like Julian Assange (who’s glimpsed very briefly here). If anything, Snowden’s the anti-Assange. He looks like half the guys working for Boston.com down the hall from my office.

Snowden knows he’ll be the story, knows we’re drawn to faces instead of numbers, and he’s torn about it. On one hand, he tells Poitras to “paint the target on my back,” so people will know who did this and, more important, why. On the other, he insists that any attention paid to him is a diversion. Since the initial news reports have barely scratched the surface of the tens of thousands of pages of government documents, those revelations will keep coming, and it’s possible their provider may yet fade behind what they tell us.

There are moments of Kafkaesque comedy in “Citizenfour.” After Snowden mentions the room could be tapped via the hotel phone handset and disconnects it, the building’s fire alarm starts beeping ominously. Is it a system test, as the front desk claims? Probably. Possibly. Maybe not. When you’ve worked, as Snowden has, in an office with surveillance drone video feeds on your desktop the way some people have stock tickers, it’s easy to assume someone’s listening. By the final hotel room sessions, Greenwald and Snowden are silently writing their conversations on scraps of paper.

Charged with three criminal counts by the US government — two of them under the 1917 Espionage Act — Snowden ended up marooned at a Moscow airport while bound for South America. He was granted temporary asylum in Russia, recently extended, where he has given interviews to the international press but has otherwise laid low. His most foolish move was appearing with Putin on television in January of this year, prodding the Russian leader on his own use of surveillance — an attempt to level the playing field that backfired and left Snowden looking naïve.

That’s not part of “Citizenfour,” and it probably should be. What’s here is more than enough to get you thinking about a world in which no one gets to have secrets except the agencies that secretly watch us. Snowden’s right: He’s not the story. You are, and what you’re going to do about it.