Reviewed by Sheila O'Malley / RogerEbert.com

Two childhood friends, who grew up in a farming village outside of Seoul, meet as adults, at random. They haven't seen one another in years. They go out for drinks and reminisce. The young woman has been studying pantomime, and she shows off some of what she has learned. She pantomimes eating a tangerine and her gestures are so specific you could swear the tangerine was really there. He is amazed at the illusion. She tells him that if he ever is hungry for anything, he can create it on his own like this.

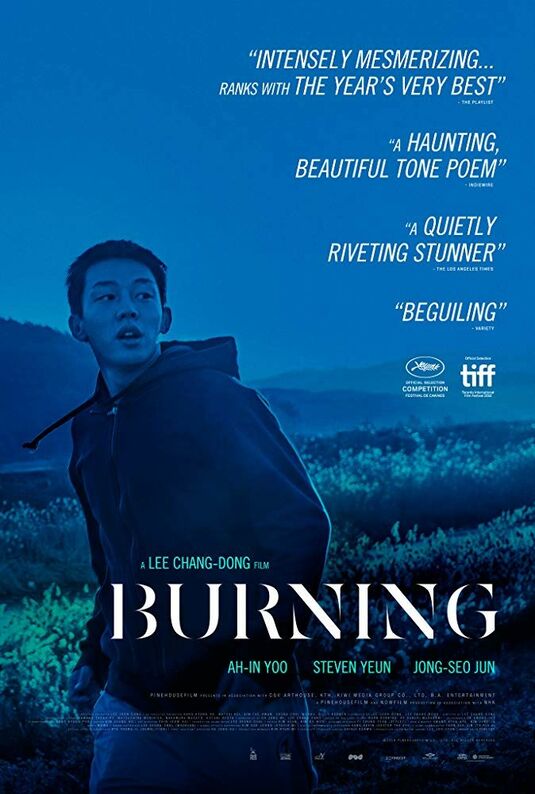

Everyone is hungry for something in "Burning," the new film from South Korean master Lee Chang-dong. How that hunger manifests, and what hunger even signifies, is up for debate. The debate itself is too dangerous to even be spoken out loud, since it threatens the class status quo. Based loosely on Haruki Murakami's short story Barn Burning, "Burning" is Lee's first film in eight years, and it is a bleak and almost Darwinian vision of the world, survival of the fittest laid bare in sometimes shocking brutality. The three main characters circle warily, looking at each other with desire, mistrust, need, never certain of the accuracy of their perceptions. Lee's explorations require depth and space. It's a great film, engrossing, suspenseful, and strange.

Jongsu (Ah-in Yoo), the young man enraptured by the pantomime, dreams of being a writer. His favorite author is Faulkner, because—he says—every time he reads a Faulkner story, it feels like his own. This makes sense since it takes a while for us to understand the layout of Jongsu's life, so hazy is it with strange relationships, missing figures, blank spaces. His father is in trouble with the law for assaulting another farmer, although the details remain vague.

His mother took off when he was little. When he runs into Haemi, (Jong-seo Jun), a girl he grew up with, dancing outside a store giving off raffle tickets, he almost doesn't recognize her. "Plastic surgery," she grins. Almost before he knows what has happened, he and Haemi have sex, and he agrees to feed her cat while she takes a trip to Africa. Rattling back and forth between Seoul and the family farm in his battered pickup truck, he is caught in an in-between state, dreaming of Haemi, waiting for her return, shoveling food for the cows, or putting out food for her cat—a cat who is never seen or heard. It's impossible to avoid the speculation that there is no cat, that Haemi made it up. But for what reason?

When Jongsu picks up Haemi at the airport on her return from Africa, he is chagrined to discover Haemi has a man in tow, a man named Ben (Steven Yeun), whom she met on her travels. The two are clearly now an item. Jongsu has a weird feeling that Ben is no good, that something is really "off" about the guy. Ben drives a Porsche, his apartment is huge and filled with beautiful artwork, he doesn't seem to have a profession. Jongsu says to Haemi, "There are so many Gatsby's in Korea." If Ben is Gatsby, then that would make Jongsu Nick Carraway and Haemi Daisy. The closer Jongsu gets to the heart of Ben, the more he sees that there's no "there there." Ben is dangerously void, maybe even a sociopath. (Yeun gives a truly chilling performance.) The class critique in "Burning" is as unsubtle as F. Scott Fitzgerald's was, and it creates unbearable tension, rage crackling off the screen. When Haemi demonstrates the Kalahari Bushmen's "hunger dance" for Ben and his friends, Jongsu notices how uncomfortable everyone is, hiding their mocking smiles. He catches Ben yawning during Haemi's dance. Haemi, so alluring to the appreciative Jongsu, is a creature of fun for these empty city slickers. Jongsu starts to feel like Haemi may be in some kind of danger.

"Burning" takes place in a world of fluctuating and amorphous borders, invisible yet pressing in on the characters. Jongsu's village is on the border of North Korea, where the air is pierced with shrieking propaganda from a loudspeaker across the hills, creating a sense of emergency among the gentle pastoral landscape, like some attack is imminent, like something dreadful lurks beyond the horizon. Haemi's cat is literally Schrodinger's cat, caught in a borderland between being and non-being. The food vanishes, the litter box is full, but the cat never manifests. The phone rings repeatedly at Jongsu's farm, but no one's on the other end. Just empty space and dead air. Images and motifs repeat, creating a fractal effect. Closets are important: each character has a closet containing secrets, mysteries (a shaft of reflected light, a gleaming knife, a pink plastic watch). Fire is important: For Haemi, it's the fire that the Kalahari Bushmen dance around. For Jongsu, it is the bonfire of his mother's clothes in the backyard, one of his only clear memories from childhood. And for Ben, as he admits to Jongsu, almost daring Jongsu to be shocked, it's the greenhouses he burns down in his spare time. "You burn down other people's greenhouses?" Jongsu asks. Ben, smiling smoothly, his face telling no tales, nods.

In one extraordinary sequence, Haemi and Ben drive out to visit Jongsu on his farm. The three sit out on the patio, get stoned and watch the sun set, the tree leaves rustling overhead, the light growing dimmer and dimmer. Haemi takes off her shirt and dances on the patio, staring off at the hills of North Korea, her silhouette undulating against the pink and purple glowing sky. Both Jongsu and Ben are frozen in their seats, as they watch her fluid gestures, her primal openness to the beauty of her own experiences. Jongsu had seen this in her when she pantomimed the tangerine. He fell in love with this part of her. Ben yawns again. By the end of the dance, she is in tears. Jongsu now knows that Ben is an enthusiastic amoral arsonist. There's a serious and alarming sense of danger, only you can't really point to its source. The whole of "Burning" feels like this.

There's so much disorienting background noise in “Burning," the traffic, the ringing of the phone, the street music, the loudspeaker blaring North Korean propaganda, Trump on the television in the corner of the room. It's hard for anyone to keep their thoughts straight; it's hard to believe what might be staring you right in the face. The tension between "what is" and "what isn't," started with Haemi's beautiful tangerine pantomime, is in urgent operation throughout. Things are never what they seem. Or, perhaps, they are, and that's even worse to contemplate. The tangerine is delicious but it's invisible. It won't provide sustenance for long. The cat was never there. Haemi made it all up. Greenhouses don't provide space for things to grow, they just stand there in the fields waiting for the arsonist's match.

Two childhood friends, who grew up in a farming village outside of Seoul, meet as adults, at random. They haven't seen one another in years. They go out for drinks and reminisce. The young woman has been studying pantomime, and she shows off some of what she has learned. She pantomimes eating a tangerine and her gestures are so specific you could swear the tangerine was really there. He is amazed at the illusion. She tells him that if he ever is hungry for anything, he can create it on his own like this.

Everyone is hungry for something in "Burning," the new film from South Korean master Lee Chang-dong. How that hunger manifests, and what hunger even signifies, is up for debate. The debate itself is too dangerous to even be spoken out loud, since it threatens the class status quo. Based loosely on Haruki Murakami's short story Barn Burning, "Burning" is Lee's first film in eight years, and it is a bleak and almost Darwinian vision of the world, survival of the fittest laid bare in sometimes shocking brutality. The three main characters circle warily, looking at each other with desire, mistrust, need, never certain of the accuracy of their perceptions. Lee's explorations require depth and space. It's a great film, engrossing, suspenseful, and strange.

Jongsu (Ah-in Yoo), the young man enraptured by the pantomime, dreams of being a writer. His favorite author is Faulkner, because—he says—every time he reads a Faulkner story, it feels like his own. This makes sense since it takes a while for us to understand the layout of Jongsu's life, so hazy is it with strange relationships, missing figures, blank spaces. His father is in trouble with the law for assaulting another farmer, although the details remain vague.

His mother took off when he was little. When he runs into Haemi, (Jong-seo Jun), a girl he grew up with, dancing outside a store giving off raffle tickets, he almost doesn't recognize her. "Plastic surgery," she grins. Almost before he knows what has happened, he and Haemi have sex, and he agrees to feed her cat while she takes a trip to Africa. Rattling back and forth between Seoul and the family farm in his battered pickup truck, he is caught in an in-between state, dreaming of Haemi, waiting for her return, shoveling food for the cows, or putting out food for her cat—a cat who is never seen or heard. It's impossible to avoid the speculation that there is no cat, that Haemi made it up. But for what reason?

When Jongsu picks up Haemi at the airport on her return from Africa, he is chagrined to discover Haemi has a man in tow, a man named Ben (Steven Yeun), whom she met on her travels. The two are clearly now an item. Jongsu has a weird feeling that Ben is no good, that something is really "off" about the guy. Ben drives a Porsche, his apartment is huge and filled with beautiful artwork, he doesn't seem to have a profession. Jongsu says to Haemi, "There are so many Gatsby's in Korea." If Ben is Gatsby, then that would make Jongsu Nick Carraway and Haemi Daisy. The closer Jongsu gets to the heart of Ben, the more he sees that there's no "there there." Ben is dangerously void, maybe even a sociopath. (Yeun gives a truly chilling performance.) The class critique in "Burning" is as unsubtle as F. Scott Fitzgerald's was, and it creates unbearable tension, rage crackling off the screen. When Haemi demonstrates the Kalahari Bushmen's "hunger dance" for Ben and his friends, Jongsu notices how uncomfortable everyone is, hiding their mocking smiles. He catches Ben yawning during Haemi's dance. Haemi, so alluring to the appreciative Jongsu, is a creature of fun for these empty city slickers. Jongsu starts to feel like Haemi may be in some kind of danger.

"Burning" takes place in a world of fluctuating and amorphous borders, invisible yet pressing in on the characters. Jongsu's village is on the border of North Korea, where the air is pierced with shrieking propaganda from a loudspeaker across the hills, creating a sense of emergency among the gentle pastoral landscape, like some attack is imminent, like something dreadful lurks beyond the horizon. Haemi's cat is literally Schrodinger's cat, caught in a borderland between being and non-being. The food vanishes, the litter box is full, but the cat never manifests. The phone rings repeatedly at Jongsu's farm, but no one's on the other end. Just empty space and dead air. Images and motifs repeat, creating a fractal effect. Closets are important: each character has a closet containing secrets, mysteries (a shaft of reflected light, a gleaming knife, a pink plastic watch). Fire is important: For Haemi, it's the fire that the Kalahari Bushmen dance around. For Jongsu, it is the bonfire of his mother's clothes in the backyard, one of his only clear memories from childhood. And for Ben, as he admits to Jongsu, almost daring Jongsu to be shocked, it's the greenhouses he burns down in his spare time. "You burn down other people's greenhouses?" Jongsu asks. Ben, smiling smoothly, his face telling no tales, nods.

In one extraordinary sequence, Haemi and Ben drive out to visit Jongsu on his farm. The three sit out on the patio, get stoned and watch the sun set, the tree leaves rustling overhead, the light growing dimmer and dimmer. Haemi takes off her shirt and dances on the patio, staring off at the hills of North Korea, her silhouette undulating against the pink and purple glowing sky. Both Jongsu and Ben are frozen in their seats, as they watch her fluid gestures, her primal openness to the beauty of her own experiences. Jongsu had seen this in her when she pantomimed the tangerine. He fell in love with this part of her. Ben yawns again. By the end of the dance, she is in tears. Jongsu now knows that Ben is an enthusiastic amoral arsonist. There's a serious and alarming sense of danger, only you can't really point to its source. The whole of "Burning" feels like this.

There's so much disorienting background noise in “Burning," the traffic, the ringing of the phone, the street music, the loudspeaker blaring North Korean propaganda, Trump on the television in the corner of the room. It's hard for anyone to keep their thoughts straight; it's hard to believe what might be staring you right in the face. The tension between "what is" and "what isn't," started with Haemi's beautiful tangerine pantomime, is in urgent operation throughout. Things are never what they seem. Or, perhaps, they are, and that's even worse to contemplate. The tangerine is delicious but it's invisible. It won't provide sustenance for long. The cat was never there. Haemi made it all up. Greenhouses don't provide space for things to grow, they just stand there in the fields waiting for the arsonist's match.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

We apologize—Movie Pass cannot be used for AHFS programs.