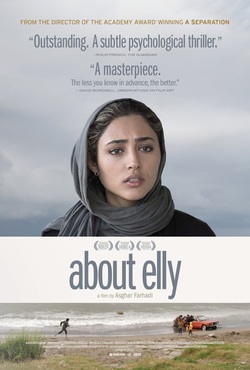

CAST & CREW

Written and directed by Asghar Farhadi

Featuring Golshifteh Farahani, Taraneh Alidousti AND Shahab Hosseini

In Persian, with English subtitles

Not Rated Running time: 118 minutes

Written and directed by Asghar Farhadi

Featuring Golshifteh Farahani, Taraneh Alidousti AND Shahab Hosseini

In Persian, with English subtitles

Not Rated Running time: 118 minutes

Reviewed by Kenneth Turan – LA Times

If the setup of the Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi’s devastating film “About Elly” sounds familiar, it’s because this story of a young woman who disappears during a festive weekend outing at a coastal resort resembles that of Michelangelo Antonioni’s classic “L’Avventura.” In both movies, a frantic and futile search ensues.

But in “L’Avventura” that search is soon abandoned. In “About Elly” the tension mounts, and accusations fly over who is to blame. With reputations at stake, lies are told. As the travelers — three married couples who have brought their children — confront the possibility that Elly may have drowned, perhaps on purpose, the camaraderie among them curdles to rancor, and they are increasingly racked by fear and guilt.

Mr. Farhadi, who achieved international recognition with the similarly complex and brilliant film “A Separation,” made after “About Elly,” uses the story for other purposes. Where Antonioni’s film evoked the metaphysical malaise of Italy’s leisure class in that country’s postwar boom, “About Elly” depicts the strains between strict Islamic traditions and modernism within Iran’s affluent, sophisticated middle class.

On one level, Mr. Farhadi’s film is a story of reckless matchmaking gone awry. An organizer of the trip, Sepideh (Golshifteh Farahani), has pressured Elly (Taraneh Alidousti), her daughter’s shy, attractive kindergarten teacher, to join the friends on a three-day getaway to a resort on the Caspian Sea. One purpose is to introduce Elly to the handsome Ahmad (Shahab Hosseini), who lives in Germany and whose short marriage to a German woman recently crumbled. In Ahmad’s words, “a bitter ending is better than endless bitterness.”

The early scenes plunge us into friendly social high jinks as the joyful vacationers arrive from Tehran and settle into a house that is considerably more decrepit than the place where they had expected to stay. As the group plays charades and volleyball, Elly, polite but nervous, lurks on the fringes. Sepideh is relieved that Ahmad and the others seem to like her.

A major lie has already been told. The old woman who rented them the beach house believes that Ahmad and Elly are newlyweds and brings the bedding for their room. From the outset, Elly, who was reluctant to come, lets it be known that she can stay for only one night.

Back-to-back crises erupt. While the men play volleyball on the beach, Elly agrees to keep an eye on the children. As she helps one of them fly a kite, she momentarily loses track of a little boy who wanders into the rough surf. The other children send up alarms, and the adults rush into the water and barely save his life. The rescue is a thrilling set piece; the cinematography makes you feel on the verge of drowning yourself as the water surges over the wobbling camera.

No sooner have the revelers heaved a collective sigh of relief than they realize that Elly is nowhere to be found, and a second search begins as they try to determine whether Elly drowned in an attempt to save the boy or left without saying goodbye. There are deepening mysteries. If she left, as she said she might, why did she leave things behind?

Sepideh, who spends much of the film on the brink of tears, and her stern, bullying husband, Amir (Mani Haghighi), nearly come to blows when the extent of her machinations comes to light. The movie gives Sepideh’s ill-conceived attempt at matchmaking a political dimension by implying it was an act of defiance on her part, and the underlying tension between the couple typifies the state of marriage in Iran’s urban middle class. At any moment, the patriarchal prerogative might explode into abuse, and beneath the civilized facade of Iranian life lurks the possibility of violent sexual warfare.

With the appearance of a distraught friend of Elly’s, the secrets and lies become more elaborate and far-fetched. And you begin to wonder to what extent the film is a critique of an entire society in which the disparity between tradition and modernity is irreconcilable.

“About Elly” is gorgeous to look at. The ever-changing sky and sea lend it a moodiness so palpable that the climate itself seems a major character dictating the course of events; the weather rules.

If the setup of the Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi’s devastating film “About Elly” sounds familiar, it’s because this story of a young woman who disappears during a festive weekend outing at a coastal resort resembles that of Michelangelo Antonioni’s classic “L’Avventura.” In both movies, a frantic and futile search ensues.

But in “L’Avventura” that search is soon abandoned. In “About Elly” the tension mounts, and accusations fly over who is to blame. With reputations at stake, lies are told. As the travelers — three married couples who have brought their children — confront the possibility that Elly may have drowned, perhaps on purpose, the camaraderie among them curdles to rancor, and they are increasingly racked by fear and guilt.

Mr. Farhadi, who achieved international recognition with the similarly complex and brilliant film “A Separation,” made after “About Elly,” uses the story for other purposes. Where Antonioni’s film evoked the metaphysical malaise of Italy’s leisure class in that country’s postwar boom, “About Elly” depicts the strains between strict Islamic traditions and modernism within Iran’s affluent, sophisticated middle class.

On one level, Mr. Farhadi’s film is a story of reckless matchmaking gone awry. An organizer of the trip, Sepideh (Golshifteh Farahani), has pressured Elly (Taraneh Alidousti), her daughter’s shy, attractive kindergarten teacher, to join the friends on a three-day getaway to a resort on the Caspian Sea. One purpose is to introduce Elly to the handsome Ahmad (Shahab Hosseini), who lives in Germany and whose short marriage to a German woman recently crumbled. In Ahmad’s words, “a bitter ending is better than endless bitterness.”

The early scenes plunge us into friendly social high jinks as the joyful vacationers arrive from Tehran and settle into a house that is considerably more decrepit than the place where they had expected to stay. As the group plays charades and volleyball, Elly, polite but nervous, lurks on the fringes. Sepideh is relieved that Ahmad and the others seem to like her.

A major lie has already been told. The old woman who rented them the beach house believes that Ahmad and Elly are newlyweds and brings the bedding for their room. From the outset, Elly, who was reluctant to come, lets it be known that she can stay for only one night.

Back-to-back crises erupt. While the men play volleyball on the beach, Elly agrees to keep an eye on the children. As she helps one of them fly a kite, she momentarily loses track of a little boy who wanders into the rough surf. The other children send up alarms, and the adults rush into the water and barely save his life. The rescue is a thrilling set piece; the cinematography makes you feel on the verge of drowning yourself as the water surges over the wobbling camera.

No sooner have the revelers heaved a collective sigh of relief than they realize that Elly is nowhere to be found, and a second search begins as they try to determine whether Elly drowned in an attempt to save the boy or left without saying goodbye. There are deepening mysteries. If she left, as she said she might, why did she leave things behind?

Sepideh, who spends much of the film on the brink of tears, and her stern, bullying husband, Amir (Mani Haghighi), nearly come to blows when the extent of her machinations comes to light. The movie gives Sepideh’s ill-conceived attempt at matchmaking a political dimension by implying it was an act of defiance on her part, and the underlying tension between the couple typifies the state of marriage in Iran’s urban middle class. At any moment, the patriarchal prerogative might explode into abuse, and beneath the civilized facade of Iranian life lurks the possibility of violent sexual warfare.

With the appearance of a distraught friend of Elly’s, the secrets and lies become more elaborate and far-fetched. And you begin to wonder to what extent the film is a critique of an entire society in which the disparity between tradition and modernity is irreconcilable.

“About Elly” is gorgeous to look at. The ever-changing sky and sea lend it a moodiness so palpable that the climate itself seems a major character dictating the course of events; the weather rules.