Reviewed by Guy Lodge / Variety Rated R 104 Mins.

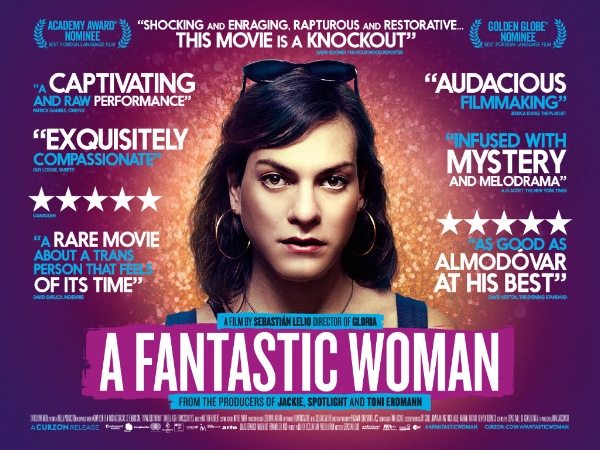

Multiple mirrors abound in frame after frame of “A Fantastic Woman,” repeatedly reflecting the woman of the title — young, beautiful, headstrong Marina — in all her, well, fantastic glory. It may seem an obvious, even clichéd, visual trope for the resourceful Chilean director Sebastián Lelio to fall back on, until it dawns on us that its very obviousness is precisely the point: We’re given every conceivable opportunity to see and perceive Marina for exactly who she is. So why do so many of those around her struggle to do the same? In this exquisitely compassionate portrait of a trans woman whose mourning for a lost lover is obstructed at every turn by individual and institutional prejudice, Lelio has crafted perhaps the most resonant and empathetic screen testament to the everyday obstacles of transgender existence since Kimberly Peirce’s “Boys Don’t Cry” in 1999. Mingled with a wily, anxious streak of noir styling, likely to earn Almodóvarian comparisons that it can weather with flair, Lelio’s film has already been snapped up for U.S. distribution by Sony Pictures Classics; a golden run of festival and arthouse success deservedly beckons.

Stylistically, “A Fantastic Woman” is a cooler, trickier object than Lelio’s previous film “Gloria,” a marvelous human comedy of middle-aged rebirth that deserved greater crossover success. The light hot-and-cold shiver that characterizes his latest sets in from the first, head-turning notes of the score, a stunning, string-based creation by British electronic musician Matthew Herbert that blends the icy momentum of vintage Herrmann with spacious gasps of silence. This disquieting soundtrack plays enigmatically over the film’s opening image of cascading waters at the spectacular Iguazau Falls on the Argentine-Brazilian border — a projection of a romantic vacation that will never take place.

Everything in the film’s opening beats is fashioned as a fine bone in the skeleton of a mystery, as divorced 57-year-old Orlando (Francisco Reyes) is introduced frequenting a shadowed sauna in downtown Santiago, later searching in vain for some missing, crucial paperwork, before meeting his glamorous, far younger girlfriend, bar singer Marina (the remarkable trans actress Daniela Vega), for a birthday dinner. That evening, Orlando suffers a fatal aneurysm out of the blue, sustaining grievous bodily injuries as he tumbles down the stairs; once Marina notifies Orlando’s brother Gapo (Luis Gnecco) that he died on the operating table, she makes a panicked dash from the hospital, high heels clacking into the city’s sodium-lit night before the police give chase. We soon learn, however, that all this genre-implying cloak-and-dagger has been but a lithe directorial red herring, indicating nothing more than the unjustified suspicion with which Marina is viewed by others.

She may look fierce in oversized shades and a tight leather pencil skirt, but Marina is no femme fatale: Nothing about her identity or her relationship to the deceased is disreputable or disingenuous. Yet as she struggles to keep a lid on her own lacerating grief, she finds herself treated as an impostor: by the immediate respondents at the hospital, who insist on addressing her by her birth ID; by a female detective (Amparo Noguera) from the senselessly enlisted Sexual Offenses Investigation Unit, who subjects her to a humiliating physical inspection; and finally by Orlando’s own family and ex-wife Sonia (a chilling, corrosive Aline Kuppenheim), who claims primary mourning rights and labels Marina a “chimera” to her face. Barred from the wake and funeral, with almost no one willing to hear her own emotional turmoil, Marina must forge an independent way to say goodbye and start anew.

As he did in “Gloria,” albeit to very different tonal effect, Lelio employs a rich range of visual and sonic devices to foreground and lay bare the inner life of a woman all too easily disregarded by mainstream, patriarchal society. Cinematographer Benjamín Echazarreta devotedly frames and lights her in a series of sympathetic tableaux that range from scrubbed naturalism to smoky artifice, the camera’s varying gaze reflecting not just her divided identity in the eye of the public, but the still-conflicted ways in which she views herself. In one ecstatic dance sequence at a gay nightclub, a bejeweled twin of sorts to the finale of “Gloria,” her image is mirrored and refracted and decked in glitter to the point of sheer fantasy — a fleeting, idealized vision of the woman that, in her mind’s eye, Marina still dreams of being. Music, too, is ingeniously used to define her from either side of the looking-glass: Lelio pulls off a daringly literal song cue in Aretha Franklin’s “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” at a point when his protagonist most requires such blunt self-assertion, while the character’s own high, ethereal rendition of Handel’s “Ombra mai fu” later on amounts to an act of regenerative grace.

Among its manifold virtues, “A Fantastic Woman” will be most vigorously embraced by factions of the LGBTQ community for its trans-as-trans casting — a detail which many recent works on this growingly prominent social issue, including “The Danish Girl” and TV’s “Transparent,” have taken flak for sidestepping. Yet Vega’s tough, expressive, subtly anguished performance deserves so much more than political praise. It’s a multi-layered, emotionally polymorphous feat of acting, nurtured with pitch-perfect sensitivity by her director, who maintains complete candor on Marina’s condition without pushing her anywhere she wouldn’t herself go. At one point in her mortifying police examination, a photographer demands that she drop the towel from her waist. She reluctantly complies, yet the camera respectfully feels no need to lower it gaze: “A Fantastic Woman” is no less assured than its heroine of her hard-won identity.

Multiple mirrors abound in frame after frame of “A Fantastic Woman,” repeatedly reflecting the woman of the title — young, beautiful, headstrong Marina — in all her, well, fantastic glory. It may seem an obvious, even clichéd, visual trope for the resourceful Chilean director Sebastián Lelio to fall back on, until it dawns on us that its very obviousness is precisely the point: We’re given every conceivable opportunity to see and perceive Marina for exactly who she is. So why do so many of those around her struggle to do the same? In this exquisitely compassionate portrait of a trans woman whose mourning for a lost lover is obstructed at every turn by individual and institutional prejudice, Lelio has crafted perhaps the most resonant and empathetic screen testament to the everyday obstacles of transgender existence since Kimberly Peirce’s “Boys Don’t Cry” in 1999. Mingled with a wily, anxious streak of noir styling, likely to earn Almodóvarian comparisons that it can weather with flair, Lelio’s film has already been snapped up for U.S. distribution by Sony Pictures Classics; a golden run of festival and arthouse success deservedly beckons.

Stylistically, “A Fantastic Woman” is a cooler, trickier object than Lelio’s previous film “Gloria,” a marvelous human comedy of middle-aged rebirth that deserved greater crossover success. The light hot-and-cold shiver that characterizes his latest sets in from the first, head-turning notes of the score, a stunning, string-based creation by British electronic musician Matthew Herbert that blends the icy momentum of vintage Herrmann with spacious gasps of silence. This disquieting soundtrack plays enigmatically over the film’s opening image of cascading waters at the spectacular Iguazau Falls on the Argentine-Brazilian border — a projection of a romantic vacation that will never take place.

Everything in the film’s opening beats is fashioned as a fine bone in the skeleton of a mystery, as divorced 57-year-old Orlando (Francisco Reyes) is introduced frequenting a shadowed sauna in downtown Santiago, later searching in vain for some missing, crucial paperwork, before meeting his glamorous, far younger girlfriend, bar singer Marina (the remarkable trans actress Daniela Vega), for a birthday dinner. That evening, Orlando suffers a fatal aneurysm out of the blue, sustaining grievous bodily injuries as he tumbles down the stairs; once Marina notifies Orlando’s brother Gapo (Luis Gnecco) that he died on the operating table, she makes a panicked dash from the hospital, high heels clacking into the city’s sodium-lit night before the police give chase. We soon learn, however, that all this genre-implying cloak-and-dagger has been but a lithe directorial red herring, indicating nothing more than the unjustified suspicion with which Marina is viewed by others.

She may look fierce in oversized shades and a tight leather pencil skirt, but Marina is no femme fatale: Nothing about her identity or her relationship to the deceased is disreputable or disingenuous. Yet as she struggles to keep a lid on her own lacerating grief, she finds herself treated as an impostor: by the immediate respondents at the hospital, who insist on addressing her by her birth ID; by a female detective (Amparo Noguera) from the senselessly enlisted Sexual Offenses Investigation Unit, who subjects her to a humiliating physical inspection; and finally by Orlando’s own family and ex-wife Sonia (a chilling, corrosive Aline Kuppenheim), who claims primary mourning rights and labels Marina a “chimera” to her face. Barred from the wake and funeral, with almost no one willing to hear her own emotional turmoil, Marina must forge an independent way to say goodbye and start anew.

As he did in “Gloria,” albeit to very different tonal effect, Lelio employs a rich range of visual and sonic devices to foreground and lay bare the inner life of a woman all too easily disregarded by mainstream, patriarchal society. Cinematographer Benjamín Echazarreta devotedly frames and lights her in a series of sympathetic tableaux that range from scrubbed naturalism to smoky artifice, the camera’s varying gaze reflecting not just her divided identity in the eye of the public, but the still-conflicted ways in which she views herself. In one ecstatic dance sequence at a gay nightclub, a bejeweled twin of sorts to the finale of “Gloria,” her image is mirrored and refracted and decked in glitter to the point of sheer fantasy — a fleeting, idealized vision of the woman that, in her mind’s eye, Marina still dreams of being. Music, too, is ingeniously used to define her from either side of the looking-glass: Lelio pulls off a daringly literal song cue in Aretha Franklin’s “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” at a point when his protagonist most requires such blunt self-assertion, while the character’s own high, ethereal rendition of Handel’s “Ombra mai fu” later on amounts to an act of regenerative grace.

Among its manifold virtues, “A Fantastic Woman” will be most vigorously embraced by factions of the LGBTQ community for its trans-as-trans casting — a detail which many recent works on this growingly prominent social issue, including “The Danish Girl” and TV’s “Transparent,” have taken flak for sidestepping. Yet Vega’s tough, expressive, subtly anguished performance deserves so much more than political praise. It’s a multi-layered, emotionally polymorphous feat of acting, nurtured with pitch-perfect sensitivity by her director, who maintains complete candor on Marina’s condition without pushing her anywhere she wouldn’t herself go. At one point in her mortifying police examination, a photographer demands that she drop the towel from her waist. She reluctantly complies, yet the camera respectfully feels no need to lower it gaze: “A Fantastic Woman” is no less assured than its heroine of her hard-won identity.

DISCUSSION FOLLOWS EVERY FILM!

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com

$6.00 Members / $10.00 Non-Members

TIVOLI THEATRE

5021 Highland Avenue I Downers Grove, IL

630-968-0219 I www.classiccinemas.com