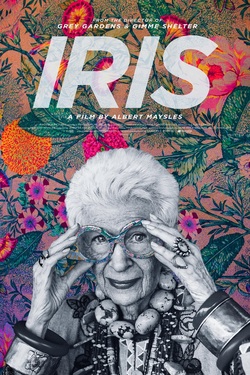

CAST & CREW

A documentary about fashion Icon

Iris Apfel from Llegendary Documentary

Filmmaker Albert Maysles

Rated PG-13 Running Time: 80 Minutes

A documentary about fashion Icon

Iris Apfel from Llegendary Documentary

Filmmaker Albert Maysles

Rated PG-13 Running Time: 80 Minutes

Reviewed by Ann Hornaday – Washington Post

It’s a beautiful accident that “Iris” is opening the same day as “Saint Laurent.” In the latter film, a dramatization of the life of designer Yves Saint Laurent, fashion is depicted as either an ascetic, monk-like endeavor or a backdrop for scandalous excess and debauchery. In the documentary “Iris,” its stylish, indefatigable protagonist restores clothing, accessories and the ritual of dressing up to the world of play and sheer pleasure.

Maybe you’ve never heard of Iris Apfel, but chances are you’ve seen her, whether as a boldfaced name photographed by veteran New York Times shooter Bill Cunningham, or in an ad for Coach. You can’t miss her: Kitted out in her signature round black glasses, her hair coiffed in a silver mullet only she can rock, she dresses to the nines, tens and elevens, her chunky necklaces and bracelets offsetting a wildly mismatched but somehow just-right ensemble, plucked either from the runway or a modest storefront boutique. She’s a one-woman cabinet of wonders, blessed with a sharp eye, natural swagger and an instinctively global — and fiercely democratic — sensibility.

Apfel has been a staple in New York fashion circles and ad campaigns for several decades, but for even her most devoted fans, she’s remained something of a mystery. In “Iris,” filmmaker Albert Maysles pulls back the boho-chic curtain to reveal an earthy, unpretentious Queens native who haggled for her first brooch as a young girl, and who later put her curatorial skills and taste to use as an interior designer. (She came by her gifts honestly: Her mother, she recalls in the film, “worshiped at the altar of the accessory.”) Along with her husband, Carl, she formed the company Old World Weavers, which specialized in high-end reproductions of hard-to-find fabrics. Their wares were particularly popular with first ladies doing White House makeovers through the years; in the film, Carl is just about to dish the dirt on Jackie Kennedy before Iris preempts him with a cautionary hush.

That’s a rare moment of spoiling the fun from a woman who, along with her husband, has pursued a life of seemingly endless curiosity, adventure and enjoyment. On their travels for Old World Weavers, she would collect textiles and jewelry from far-off climes, then put them together in bold, novel ways, a habit she keeps to this day. Maysles follows Iris around as she speaks with design students, banters with Carl, visits with photographer Bruce Weber and shows off her collection of gorgeous clothing. But she really comes to life when she’s on the hunt, whether prowling through a Harlem shop specializing in African goods or flea-marketing near her second home in Palm Beach, Fla.

The climax of “Iris” centers on a 2005 museum exhibition of her collection of clothing and accessories, which showed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art before traveling to other venues. It’s a spectacular example, not just of bygone craftsmanship (“They don’t know how to sew, they don’t know how to drape, they’re media freaks,” she complains of young designers), but where artifice and authenticity meet in artful self-creation. As luscious as the material objects are in “Iris,” and as indomitable as its feisty leading lady is, a whiff of melancholy begins to take hold. As it happens, Maysles himself died just months before the movie was released this year, at the age of 88. For their part, Iris and Carl are still kicking, at 93 and 101, respectively. “Iris” serves as a spirited, often dazzling primer in how to fight the dying of the light and feel fabulous while doing it.

It’s a beautiful accident that “Iris” is opening the same day as “Saint Laurent.” In the latter film, a dramatization of the life of designer Yves Saint Laurent, fashion is depicted as either an ascetic, monk-like endeavor or a backdrop for scandalous excess and debauchery. In the documentary “Iris,” its stylish, indefatigable protagonist restores clothing, accessories and the ritual of dressing up to the world of play and sheer pleasure.

Maybe you’ve never heard of Iris Apfel, but chances are you’ve seen her, whether as a boldfaced name photographed by veteran New York Times shooter Bill Cunningham, or in an ad for Coach. You can’t miss her: Kitted out in her signature round black glasses, her hair coiffed in a silver mullet only she can rock, she dresses to the nines, tens and elevens, her chunky necklaces and bracelets offsetting a wildly mismatched but somehow just-right ensemble, plucked either from the runway or a modest storefront boutique. She’s a one-woman cabinet of wonders, blessed with a sharp eye, natural swagger and an instinctively global — and fiercely democratic — sensibility.

Apfel has been a staple in New York fashion circles and ad campaigns for several decades, but for even her most devoted fans, she’s remained something of a mystery. In “Iris,” filmmaker Albert Maysles pulls back the boho-chic curtain to reveal an earthy, unpretentious Queens native who haggled for her first brooch as a young girl, and who later put her curatorial skills and taste to use as an interior designer. (She came by her gifts honestly: Her mother, she recalls in the film, “worshiped at the altar of the accessory.”) Along with her husband, Carl, she formed the company Old World Weavers, which specialized in high-end reproductions of hard-to-find fabrics. Their wares were particularly popular with first ladies doing White House makeovers through the years; in the film, Carl is just about to dish the dirt on Jackie Kennedy before Iris preempts him with a cautionary hush.

That’s a rare moment of spoiling the fun from a woman who, along with her husband, has pursued a life of seemingly endless curiosity, adventure and enjoyment. On their travels for Old World Weavers, she would collect textiles and jewelry from far-off climes, then put them together in bold, novel ways, a habit she keeps to this day. Maysles follows Iris around as she speaks with design students, banters with Carl, visits with photographer Bruce Weber and shows off her collection of gorgeous clothing. But she really comes to life when she’s on the hunt, whether prowling through a Harlem shop specializing in African goods or flea-marketing near her second home in Palm Beach, Fla.

The climax of “Iris” centers on a 2005 museum exhibition of her collection of clothing and accessories, which showed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art before traveling to other venues. It’s a spectacular example, not just of bygone craftsmanship (“They don’t know how to sew, they don’t know how to drape, they’re media freaks,” she complains of young designers), but where artifice and authenticity meet in artful self-creation. As luscious as the material objects are in “Iris,” and as indomitable as its feisty leading lady is, a whiff of melancholy begins to take hold. As it happens, Maysles himself died just months before the movie was released this year, at the age of 88. For their part, Iris and Carl are still kicking, at 93 and 101, respectively. “Iris” serves as a spirited, often dazzling primer in how to fight the dying of the light and feel fabulous while doing it.